Commissioned by BFI Video for an April 2015 release. — J.R.

Charlie Chaplin, the late Gilbert Adair liked to assert, doesn’t simply belong to film history; he belongs to history. And the same might be said for Roberto Rossellini’s first major feature, Roma città aperta. Even though it’s routinely regarded as a landmark in film history — the film that decisively put Italian Neorealism on the global map — one could argue that its lasting importance owes far more to the major role it played in humanizing the Italian population for the rest of the world after it emerged from over two decades of Fascist rule under Benito Mussolini.

We don’t hear much about that Fascist rule in Rome Open City, an omission that entails a historical simplification, albeit an understandable as well as an expedient one — not so much an expression of “first things first” as an expression of “second things first,” viewed by most audiences around the world from the vantage point of the war’s end. A project that was first conceived in August 1944, only two months after the Allies had forced the Nazis out of Rome, the film was driven primarily by a desire to expose the brutalities and indignities suffered by Romans under the German occupation as well as the discovery of a common purpose between the Communist and Catholic partisans who had opposed it. If we bear in mind how many contemporary viewers compared Rome Open City to newsreels — even when, as with John Mason Brown in the Saturday Review of Literature, they knew that this impression was an artistically crafted illusion (“Its anguishes…seem as genuine as if, by coincidence, an appalling sequence of events had just happened to take place in orderly narrative fashion before the newsreel cameras”) — or how many of Rossellini’s subsequent films testified to the place and time of their making, sometimes even signaled by their titles (Germany Year Zero, Europa ’51, India ’58), it stands to reason that many of the most valuable lessons to be learned from Rossellini’s actuality reside in the details that date the most today, seven decades later. The melodramatically manipulative music of Rossellini’s brother Renzo, for instance, seems to have functioned much better for audiences in the mid-40s than they are apt to register today. And more generally, nothing dates more than the codes and markers of realism (or, for that matter, Neorealism) itself, especially now that we know today that many of the starring roles in Rome Open City were played by professional actors (even if several of these were relative or complete newcomers to filmmaking), and that most of the interior scenes were shot in studio spaces (even if some of these had to be improvised within available locations).

Most telling of all, perhaps, is how relatively slick Rome Open City looks now, as compared to how rough it looked to most audiences at the time. By necessity, the film was shot quickly, intermittently, and haphazardly on borrowed and degraded film stock, which originally led many potential distributors to reject the film as substandard (before the film eventually emerged as a hit during its first Paris run), but today it is more apt to evoke the expressionist flavour of film noir, which the suspenseful pacing and claustrophobic interiors only help to intensify. Insofar as film noir is itself an ahistorical genre (since hardly anyone at the time was calling it such), this only clarifies further that our valuation of Rome Open City as a time capsule has to factor in all the stylistic practices that signified plausible realism and immediacy in the mid-40s. The same caveat applies to the sexual stereotyping: characterizing the most heartless and evil of the Nazi tormenters, Bergmann (Harry Feist) and Ingrid (Giovanna Galletti), with gay mannerisms (an association of guilt with “decadence” subsequently echoed in Germany Year Zero’s homosexual schoolteacher), or dressing up and lighting Marina (Maria Michi), the drug-addicted lover and betrayer of Communist leader Manfredi (Marcello Pagliero), as a standard-issue femme fatale. Italian Rossellini expert Adriano Aprà has also cited the expressionist lighting in the German torture chamber that explicitly turns Manfredi into a Christ figure.

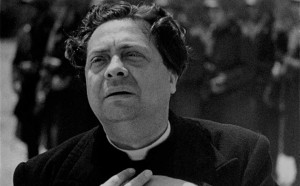

Where Rossellini’s genius comes into play is not only in his mastery of such conventions, but also in his resourcefulness of accommodating them to more unorthodox decisions. Harry Feist, who played Bergmann, was a dancer, and Maria Michi, cast as Marina, was a theatre usherette, reportedly chosen because of her romantic ties to Sergio Amidei, the principal screenwriter (whose apartment in Rome was used as one of the locations). Rosselini’s two most memorable actors — Aldo Fabrizi as Don Pietro and Anna Magnani as Pina — were both professionals, but cast against type: Fabrizi was a comic monologist who specialized in dialects and had little film experience; Magnani had already appeared in sixteen films, but was mainly known to audiences for her broad comedy in music-hall revues. Casting comedians as tragedians was not entirely unprecedented — one recalls Erich von Stroheim’s employment of Zasu Pitts as Trina in Greed — but Rossellini’s way of using them was nothing short of inspired. In the case of Fabrizi, a friend of Fellini, he was sufficiently aware of his actor’s comic talents to exploit them, both in our introduction to his character (a soccer game with his beloved schoolboys) and in an inspired piece of pantomime in an antique shop where he prudishly rearranges a couple of nude statues. (The character was based loosely on a real-life suburban priest named Don Pietro Pappagallo, who had been making forged identity cards for the Resistance.) And with Magnani, along with his cowriters Amidei and Federico Fellini, he adroitly has his other most charismatic player killed off when the film is scarcely more than half over, producing an emotional shock and a necessary realignment of identification that is comparable in certain respects to Alfred Hitchcock’s disposal of Janet Leigh in the first third of Psycho some fifteen years later.

More generally, much of the power of Rome Open City comes from the mastery of the staging, a mastery that comes in part from simplifying and orchestrating the principal points of dramatic interest for maximal effect It’s been noted more than once that the layout of the Nazi headquarters improbably places the torture chamber on one side of Bergmann’s office and a plush lounge where classical music is played on another, while the Italian Fascists who would have been working in these headquarters are noticeably absent, but all of these arrangements powerfully serve the dramaturgy in terms of sound as well as image.

Significantly, Pina’s sudden death by machine-gun while running after her arrested fiancé Francesco (Francesco Grandjacquet) as he gets driven away in a van, along with the collapse of Manfredi’s tortured body at Nazi headquarters, are the two iconic moments cited most often in Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma as testaments to Italy’s martyrdom under the Nazi occupation. And as the late Peter Brunette noted in his book-length study of Rossellini, the placement of the camera inside the retreating van contributes immeasurably to the power of the first of these moments, whereas the earlier assertion of Manfredi that he isn’t a hero only helps to underline the fact that his heroic resistance and death are seen on a life-size rather than a monumental scale.

It could even be argued that what was most innovative and startling about Rome Open City in 1945 was more a matter of content than one of style. Brunette has also argued that the documentary-like ‘antinarrative devices of La nave bianca, Un pilota ritorna, and L’uomo dalla croce’ (Rossellini’s first three and only previous features, all made during the Fascist period) are abandoned here for the sake of a more conventional style and narrative, and would be resumed and expanded in Rossellini’s far more experimental subsequent feature, Paisà (1946), the second part of his so-called war trilogy.

But commercially and otherwise, it was this film that ushered in the world-wide embrace of Italian cinema in general and Italian Neorealism in particular at the war’s end. In New York, where it opened less than a year after it had been shot, on February 25, 1946, at a small (299-seat) cinema significantly called the World, it ran for an unprecedented twenty consecutive months, thanks to the promotional efforts of Rodney Geiger (an enthusiastic U.S. army private who had befriended Rossellini in Rome the previous year) working with New York exhibitors Arthur Mayer and Joseph Burstyn, not to mention the immediacy of what it had to impart. In the process, it effectively launched an upsurge in stateside foreign film distribution as well as an escalation in independent arthouse exhibition that would flourish for over a decade. And for Rossellini it led to both his extended romantic and professional partnership with Ingrid Bergman, then at the height of her Hollywood fame (who wrote him a rapturous fan letter after seeing the film, offering her acting services) and a long and various career in filmmaking that biographer Tag Gallagher has aptly termed an adventure.