From the Chicago Reader (July 22, 1988). — J.R.

MIDNIGHT RUN

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Martin Brest

Written by George Gallo

With Robert De Niro, Charles Grodin, Yaphet Kotto, John Ashton, and Dennis Farina.

There’s a certain unavoidable imposture in the way critics (and the Academy Awards) generally break commercial movies into constituent parts and distinct contributions. To do this is to assume, first of all, that a movie’s official credits are an accurate indication of who did what offscreen, which is often not the case. It assumes further that one can easily isolate such separate aspects of movies as photography, direction, script, and acting while experiencing and judging their combined effects, the movie as a whole — it assumes, that is, that one can reverse the filmmaking process and, through powers of sheer induction, come up with precise recipes, the same way that producers and packagers do.

Like a butcher slicing up a carcass and pricing its various parts, the film reviewer typically regards each movie as a collection of individual expressions, each one to be rated on a separate evaluative scale. Of course, some of the greatest films tend to elude such divisions: how can one separate Chaplin’s acting from his directing in Monsieur Verdoux, or Tati’s directing from his script in PlayTime? Even when different individuals are involved, the question of where one contribution leaves off and another begins is often less easy to sort out than critics pretend. A month ago, I had a lot of trouble trying to figure out how to assign merit badges for Who Framed Roger Rabbit. And how do we distinguish between Marlene Dietrich’s performances in Josef von Sternberg’s films and Sternberg’s modeling of them? How can we separate the music from the mise en scene in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey or his Full Metal Jacket?

It’s in the less successful and relatively uncentered films — that is, the bulk of what we see — that the slicing-up strategy makes most sense, but even here the issues are by no means simple. My first instinct regarding Midnight Run was to assign everything I liked in the film to Robert De Niro and Charles Grodin, and to discredit everything and everyone else. The overall impression I had was of two gifted actors dutifully (if creatively) working their way through the kind of mindless sludge that Burt Reynolds participates in for the drive-in crowds, where every character, plot detail, and line of dialogue is guaranteed authenticity by having been encountered dozens of times before, and where the bad guys and the good guys are as easy to tell apart as cowboys and Indians.

I stand by at least part of this judgment, and will be expounding on certain aspects of it below. But I’d also like to introduce a measure of doubt at the outset by noting that in most cases such formulations are too easily arrived at to be entirely trustworthy. Critics are supposed to be Insiders, but even the ones working in the bowels of the industry are seldom able to trace a film’s creation step by step; and ironically, those who are closest to the process are usually the ones who are least equipped to judge the results from an audience’s perspective. So all of us try to make educated guesses about what produced the on-screen evidence. As Exhibit A, here is the review that I started a couple of hours after seeing Midnight Run:

If it were merely a matter of script, direction, and technical credits, this formula cross-country-chase comedy wouldn’t be worth a minute of one’s time, much less the price of a movie ticket. Martin Brest, who launched his career a little over a decade ago by leaping from a forgettable $33,000 independent feature called Hot Tomorrows to a $5 million heist comedy called Going in Style, followed by Beverly Hills Cop, comes on like a competent if faceless TV director, scoring with all the desired effects of his mechanical mise en scene, but leaving no discernible memory traces behind him. The script by George Gallo, a newcomer whose only previously produced screenplay was for Wise Guys (1986), is as formulaic as they come, even down to multiple and periodic plot twists that seem to come along before every invisible station break. Danny Elfman’s pop score is aggressively banal, and Donald Thorin’s cinematography is thoroughly unremarkable. What this movie has is lively performances by two of the best actors in the business, Robert De Niro and Charles Grodin; without them, it would be little more than a hole in the screen.

This isn’t the kind of movie one would ordinarily expect De Niro to be doing, although he justifies his decision to work with such material in a number of ways. Far from slumming or moonlighting, he’s often raising the movie’s shopworn elements to his own level, and generously allowing his talented costar, the underrated Grodin, to get a crack at the popular audience that his usual roles preclude. (Grodin usually plays satiric versions of mainstream nerds, in movies like The Heartbreak Kid, Real Life, and Ishtar. Here he’s playing a genuine eccentric and crank idealist — a mousy accountant who embezzles $15 million from a mob so that he can give most of it to charity.) This is basically a buddy movie crammed with all the cliches that one associates with such light entertainments, but the combination of star (De Niro as a bounty hunter) and character actor (Grodin as his prey) gives it some class and energy as well as some style. A lot of deadwood stands between these two actors and the audience, but if one regards it as a vehicle rather than an obstacle, one might say that De Niro and Grodin manage to ignite the kindling.

When I wrote the above, I had seen one previous Martin Brest film, Hot Tomorrows, which I remembered so dimly that I had to consult Pauline Kael’s review before I could recall enough of it to call it “forgettable.” The following night, I looked at Going in Style for the first time on tape, and that prompted the beginning of a second review, Exhibit B:

While I still haven’t caught up with Beverly Hills Cop, Martin Brest’s other features to date all have certain traits in common. Hot Tomorrows, Going in Style, and Midnight Run are all mainly comic buddy movies with melancholy subtexts; all encourage their lead actors to ham it up, and each has an aggressive and synthetic musical score (ersatz 30s musical numbers in Hot Tomorrows, ersatz Dixieland in Going in Style, ersatz rock in Midnight Run) that editorializes and not so gently prods the audience, telling us how and when to react. Giving actors a lot of freedom while giving spectators very little freedom at all produces a strange push-me/pull-you effect reminiscent of certain popular TV series. The usual point of such shows isn’t surprise but the chance to savor minor variations on the already known — not marveling at what Ralph Kramden says on The Honeymooners, but appreciating the particular inflection that Jackie Gleason brings to the line this time. This strategy, a triumph of embroidery over design, would be unthinkable without an interminable backlog of familiar lines, gestures, and attitudes, and that is precisely what lurks behind De Niro’s role as a bounty hunter and former cop in Midnight Run.

Jack Walsh (De Niro) is hired by the mob to track down Jonathan Mardukas (Charles Grodin), who has jumped bail after being arrested for embezzling $15 million of the mob’s money. Walsh’s mission, for which he’ll be paid $100,000, is to locate Mardukas and deliver him to the authorities in Los Angeles within five days. Very early on, Walsh captures Mardukas in New York by posing as an FBI agent, and as soon as we see that the men dislike each other, we automatically know that before the movie is over, they’ll wind up as friends; we also know that a steady stream of plot twists, car chases, and other complications will intervene between New York and Los Angeles. The only genuine surprises in store are not what happens but how De Niro and Grodin articulate and react to the predictable events.

So there you have two possible takes on Midnight Run. While they’re not exactly antithetical, one can’t call them wholly compatible either. The first assumes that De Niro and Grodin wrested control of the movie away from its hackneyed script and direction; the second implies that the hackneyed script and direction allowed for and even helped to create their enjoyable performances. The reason for juxtaposing these two positions isn’t to resolve them but to suggest that such critical arguments are usually motored by presumptions rather than by hard facts.

A few soft facts: The press materials for Midnight Run quote Brest as saying that this movie combines the meticulously preplanned shooting style of Hot Tomorrows with the more improvisational style of Beverly Hills Cop, “where the script was changed each and every day,” apparently according to the inspirations of Eddie Murphy. Brest also mentions that the plot of Midnight Run grew out of an anecdote told him by screenwriter George Gallo while they were discussing another project, and that neither De Niro nor Grodin was considered at first.

A third possible review of Midnight Run might deal with De Niro and Grodin in relation to each other, rather than as some sort of united front that functions either with or against the rest of the movie; and a fourth could deal with how the movie works independently of what they bring to it. I offer Exhibits C and D not so much to provide a final verdict as to indicate some of the main issues that are involved.

Now that he’s almost 45, Robert De Niro remains our only plausible successor to Marlon Brando, but there’s an important difference: while Brando at the same age (in 1969) was already reduced mainly to camping his way through a lot of second- and third-rate movies, rarely disguising his contempt for them, De Niro continues to show a special talent for adjusting each performance to the special needs of the movie at hand. While it’s difficult to imagine Brando at any age playing in a buddy movie, De Niro manages to divide the territory of Midnight Run with Charles Grodin, effectively strutting his stuff without ever overwhelming his fellow actor.

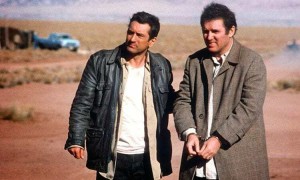

De Niro is Jack, a former Chicago cop who was drummed off the force for refusing to be in on the take; he now works as a bounty hunter. Grodin plays John, an accountant who embezzled from the mob in order to give most of the money to charity. Both, in other words, are soured idealists, but it takes them most of the movie to discover that their similarity counts for more than their differences.

Jack is attempting to get John, in handcuffs, from New York to LA while the FBI, the mob, and a rival bounty hunter are all in hot pursuit; John steadily needles his captor about the junk food he eats, the cigarettes he smokes, the way he tips in restaurants, and his unrealistic dreams of opening a coffee shop with his bounty money. Showering Jack with unsolicited personal advice, John even convinces him to visit his former wife and teenage daughter in Chicago, and later to give up his fantasy of somehow eventually getting back together with them. Meanwhile John is learning that Jack, under his seeming hardness and cynicism, has a personal moral code as strict as his own.

These are the basic givens, but what De Niro and Grodin do with these characters provides the meat of the movie. Essential to their collaboration is the immutable fact that De Niro is a star, a construct designed to resolve contradictions, while Grodin is a character actor, a construct designed to assert contradictions. In many of De Niro’s best star roles — such as in The Godfather Part II, Taxi Driver, New York, New York, Raging Bull, and The King of Comedy — he plays a lower-income nobody who becomes a star while remaining a nobody — a loser even in success. (Perhaps his decision to act in Midnight Run can be ascribed to a desire to make use of that persona in a less arty vehicle.) The specter of failure also rests heavily on the head of Jack, and De Niro’s subtle manipulation of this fact becomes the pipeline for his intimacy with the audience — contextualizing his rage, sometimes giving it unexpected and witty undertones (while threatening on the phone to his boss, a seedy bail bondsman, to shoot John and “dump him in the fuckin’ swamp,” he nods to John to signify that he doesn’t mean it). Jack relishes his sassy impersonations of the FBI agent whose badge he’s stolen, shielding his sense of defeat with gruff bravado. The contradiction resolved in all these pyrotechnics is that he’s a loser who scores, again and again.

Grodin, by contrast, is a character actor whose most memorable past performances convert bland, everyday nobodies — a suburban veterinarian in Real Life, a sporting goods salesman in The Heartbreak Kid, a CIA operative in Ishtar — into semipsychotic martians. Grodin’s tactics, unlike De Niro’s, are designed to make his satiric characters difficult to identify with. But for the purposes of Midnight Run, in order to mesh with De Niro, he reverses his usual technique, and his John comes across as a daffy eccentric at the beginning who gradually imposes his commonsense wisdom. Unlike Jack, John is denied a biographical density — we never learn very much about his past or marriage — but when he takes over Jack’s trick of impersonating an FBI agent to get hold of some cash in a western bar, the audience winds up cheering for him, too; he is no longer imbued with the glacial otherness of his standard “normal” parts. (Repeatedly, he and Jack become actors in their various deceptions and impersonations, and it is at these moments that De Niro and Grodin’s interplay most often flourishes.) Yet because of his calculated incompleteness as a character — the fact that the oddball and commonplace aspects of his character never quite blend — he remains a character actor and a contradiction, existing in a separate register from De Niro’s Jack. Consequently, their eventual coming together as friends is more philosophical than an expression of any material equality in screen presence. (Rating: three stars.)

Back in the good old days, before TV became the dominant medium, one could argue that a lot of cliche-ridden movies were sustained by their sincerity and by the capacity of audiences to believe in them. Movies were bigger than spectators then, and there was something about their imposing size that compelled some form of belief in spite of everything. But since they’ve mainly succumbed to the more blase attitudes governing TV — where images are smaller than spectators and less likely to inspire the same degree of commitment and involvement — their cliches all seem to have built-in disclaimers. Consider Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and their multiple spinoffs; consider the James Bond films and Brian De Palma’s exercises in Hitchcockism: a working premise behind all these movies is that nobody is supposed to believe in them, not even for an instant. They are second-degree fantasies from the word go; they convert the old suspension of disbelief into a new, TV-age attitude, suspension of belief.

In the case of Midnight Run — a dull replay of cross-country crime/thriller/buddy movie/action/adventure/comedy conventions, in which the separate sections of the plot become almost interchangeable, and all seem to have been dictated by a computer — the audience’s forced enthusiasm has a sense of desperation and alienation about it. Filmmakers and spectators are both participating in the same game of disbelief, but neither is quite owning up to it. It’s like the old gag about the comedy convention, where comics amuse one another by reciting numbers that stand for the jokes they already know.

Outlandish coincidences and improbabilities can be dropped into such projects like raisins without interrupting the flow, because short attention spans and the bite-size narrative units of TV pacing both guarantee that the movie will switch tracks every ten minutes or so anyway, regardless of what this does to continuity or logic. It’s a requirement of such packages that the heroes all wind up with everything they want (and, if possible, more), while the villains all get their just desserts. The aftereffect of such cynical engineering is generally rather sad — as if nobody believed today that any kind of plausible happy ending was actually possible.

On the slimmest of pretexts, the two heroes of Midnight Run, a bounty hunter and an embezzler, make their way across the U.S. by train, car, truck, on foot, and by hopping a freight car. (There are also episodes with a rushing stream and an antique plane.) When an unlikely car chase develops, it’s the logic of other formula car chases that takes over; the relevance and significance of the chase to this plot and these characters is secondary, so the latter are blithely mauled for the sake of some glib excess. Jangling electric guitars and other pop paraphernalia periodically appear on the sound track to denote danger, suspense, haste, jaunty amusement, etc, apparently because without them the cliches might be too affectless by now to register at all. Most of the humor pivots on the bounty hunter getting the goat of a public official — a staple of film comedy at least since the Keystone Kops — but not much conviction is felt behind this, either.

What does this movie ask us to accept? That the bounty hunter and the embezzler he’s supposed to deliver from New York to Los Angeles, who come from totally different walks of life, live in different cities, and have only just met, discover after most of the movie is over and they’ve spent several days together that their separate lives have been thwarted and determined by the same mobster, who happens to be chasing them. Presumably the scriptwriter, who aims for a new twist every few minutes, decided to save this little plum for somewhere near the end, regardless of how silly it made the rest of the movie seem.

The virtue of such frantic busyness is that at least the movie moves. Director Martin Brest and scriptwriter George Gallo are determined to keep their war-horse in constant motion, and if they have to do this by making all, of the villains Johnny Onenotes — a glowering FBI agent who filches cigarettes from prisoners (Yaphet Kotto), a grizzled slob of a rival bounty hunter (John Ashton), a stock mobster (Dennis Farina) — at least that makes the proceedings easier to follow. Despite all the calculated plot turnarounds, if you see only 15 minutes of this movie, you’ve seen it all. (Rating: one star.)