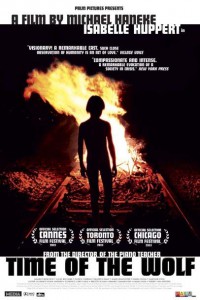

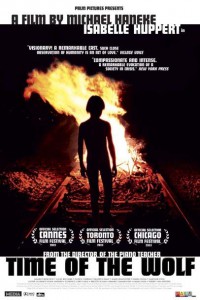

From the Chicago Reader (April 23, 2004). — J.R.

Michael Haneke’s best films — like The Seventh Continent and Code Unknown — tend to create their own world and their own rules, whereas others — like Benny’s Video, Funny Games, and this postapocalyptic tale — offer variations on films others have already made. But Haneke is still a masterful director, and his authority carries this well-acted and attractively shot account of a family from an unnamed city trying to survive in the sticks after an unspecified catastrophe. (Some have criticized the lack of explanation, but the relatively lame and familiar backstories of most such movies hardly seem an improvement.) We’ve seen much of this before, but Haneke’s theme of civilization gradually sliding away remains timely. With Isabelle Huppert and Patrice Chereau; most of the dialogue is in subtitled French. 110 min. A 35-millimeter ‘Scope print will be shown. Gene Siskel Film Center.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 1, 1990). — J.R.

Preston Sturges’s second feature as writer-director (1940, 66 min.) is in many ways the most underrated of his movies — a riotous comedy-satire about capitalism that bites so deep it hurts. An ambitious but impoverished office clerk (Dick Powell) is determined to strike it rich in a contest with a stupid slogan (“If you can’t sleep at night, it isn’t the coffee, it’s the bunk”). He’s tricked by a few of his coworkers into believing that he’s actually won, promptly gets promoted, and proceeds to go on a shopping spree for his neighbors and relatives. Like much of Sturges’s finest work, this captures the mood of the Depression more completely than most 30s pictures, and the brilliantly polyphonic script repeats the hero’s dim-witted slogan so many times that it eventually becomes a kind of crazed tribal incantation. As usual, Sturges’s supporting cast (including Ellen Drew, William Demarest, and Raymond Walburn) is luminous, and he uses it like instruments in a madcap concerto. (JR)

Read more

Read more

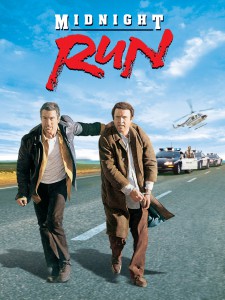

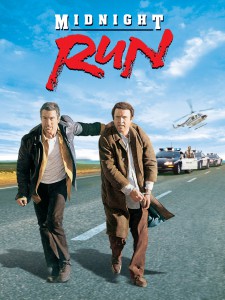

From the Chicago Reader (July 22, 1988). — J.R.

MIDNIGHT RUN

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Martin Brest

Written by George Gallo

With Robert De Niro, Charles Grodin, Yaphet Kotto, John Ashton, and Dennis Farina.

There’s a certain unavoidable imposture in the way critics (and the Academy Awards) generally break commercial movies into constituent parts and distinct contributions. To do this is to assume, first of all, that a movie’s official credits are an accurate indication of who did what offscreen, which is often not the case. It assumes further that one can easily isolate such separate aspects of movies as photography, direction, script, and acting while experiencing and judging their combined effects, the movie as a whole — it assumes, that is, that one can reverse the filmmaking process and, through powers of sheer induction, come up with precise recipes, the same way that producers and packagers do.

Like a butcher slicing up a carcass and pricing its various parts, the film reviewer typically regards each movie as a collection of individual expressions, each one to be rated on a separate evaluative scale. Of course, some of the greatest films tend to elude such divisions: how can one separate Chaplin’s acting from his directing in Monsieur Verdoux, or Tati’s directing from his script in PlayTime? Read more