Written for the May 2016 Artforum. — J.R.

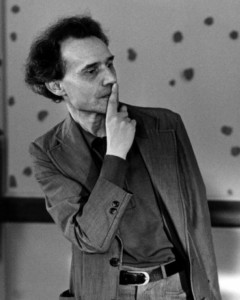

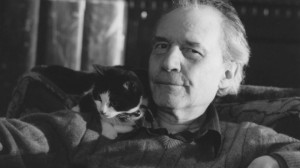

Although Jacques Rivette was the first of the Cahiers du Cinéma critics to embark on filmmaking, he differed from his colleagues—Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer, François Truffaut—in remaining a cult figure rather than an arthouse staple. His career was hampered by various false starts, delays, and interruptions, and then it abruptly ended in 2009 with the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, six years before his recent death. But his legacy is immense.

His career can easily be divided into two parts, although it’s not so easy to pinpoint a precise dividing line between them. And for those who knew him well or even casually, as I did, it’s hard to prefer the first portion to the second without feeling somewhat guilty.

Common to both parts is a preoccupation with mise-en-scène and the mysterious aspects of collective work, offset by the more solitary and dictatorial tasks of plotting and editing. Rivette’s own collective work was frequently enhanced by improvisation—with actors, with onscreen or offscreen musicians, or with dialogue written just prior to shooting (either by actors or screenwriters)—while the more solitary work of plotting and editing emulated the Godardian paradigm of converting chance into destiny. Each of Rivette’s films proposed a somewhat different method for arriving at this dialectical combination of elements, reinventing the director’s role in the process, but it’s hardly coincidental that the twin themes of togetherness and solitude are what invariably emerged from the alchemy.

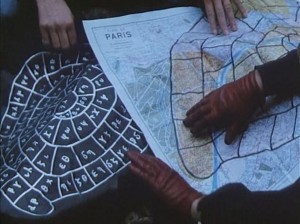

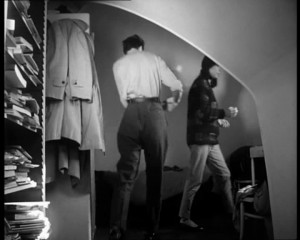

The first part of Rivette’s career encompasses both his activity over two decades as a film critic and his boldest experiments as a director. He began contributing to Gazette du Cinéma in 1950 and soon after to Cahiers du Cinéma, which he also edited from 1963 to 1965. Among his most significant critical engagements were those with Howard Hawks, Roberto Rossellini, Fritz Lang, and Jean Renoir—the latter especially in the three-part TV documentary Jean Renoir, le patron (1967). By Rivette’s own account, the editing of Renoir clips helped to inspire his subsequent audacious experiments: L’amour fou (1969), Out 1: Noli me tangere (1971), Out 1: Spectre (1972), Céline et Julie vont en bateau (Céline and Julie Go Boating, 1974), Duelle (1976), Noroît (1976), and Le Pont du Nord (1981). This stretch also includes his heroically ambitious and haunting if relatively amateurish first feature, Paris Belongs to Us (1961) as well as the less characteristic La religieuse (The Nun, 1966) and the abortive Merry-Go-Round (1981).

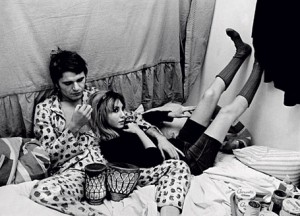

It is of this first portion of Rivette’s career that his fellow critic and director André Téchiné was speaking when he told Le Monde, shortly after the filmmaker’s death this past January, that “For [Rivette], cinema was the equivalent of a lack of restraint, a leap into the void. His films defied rules, limits, the very notions of mise-en-scène, mastery, and duration. With L’amour fou, Out 1, or Le Pont du Nord, he invented the experiences of radical cinema, insanely exciting. I don’t know any filmmaker who protected himself less than he did.” His most important producer during this period was Stéphane Tchalgadjieff, who enabled him to make Out 1, Duelle, and Noroît—the latter constituting two parts of a projected four-feature cycle that capsized when Rivette suffered a nervous collapse a few days into the shooting of a third, the never-completed Marie et Julien. His most important personal relationship was with Marilù Parolini , an Italian photographer and screenwriter he briefly married, and with whom he can be seen (while she was working as a secretary at Cahiers du Cinéma) in Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s 1961 Chronique d’un été.

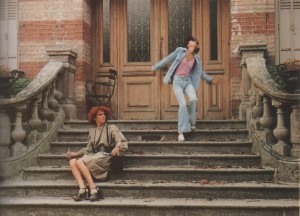

The second part of his career, a dozen more features, was safer and saner, reflecting decisions made on behalf of life over art — not a betrayal of the concerns of his earlier work, but a more “reasonable” application of them: L’amour par terre (Love on the Ground, 1984), Hurlevent (Wuthering Heights, 1985), La bande des quatre (Gang of Four, 1989), La belle noiseuse (1991), Jeanne la Pucelle (Joan the Maid; in two parts, both 1994), Haut bas fragile (Up, Down, Fragile, 1995), Secret défense (1998), Va savoir (2001), Histoire de Marie et Julien (The Story of Marie and Julien, 2003–a belated retooling of Marie et Julien with a different cast and crew), Ne touchez pas la hache (The Duchess of Langeais, 2007), and, finally, Around a Small Mountain 36 vues du Pic Saint-Loup (2009). Rivette’s only producer during this period was Martine Marignac, and his most important relationship was with Véronique Manniez, author of a 1998 book about Secret défense, who married him shortly after he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and cared for him for the remainder of his life.

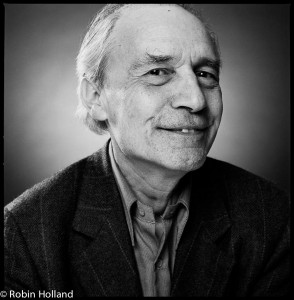

My own acquaintance with Rivette, in the mid-’70s to the early ’80s, derived from my friendship with the late Argentinian screenwriter Eduardo de Gregorio, who worked on Céline and Julie, Duelle, Noroît, Merry-Go-Round, and the unrealized Phénix. Thanks to this connection, I attended several private screenings of Céline and Julie in its final workprint form, interviewed Rivette in my Paris flat, and observed parts of the shooting of both Duelle (in Paris) and Noroît (in Brittany), and even accompanied Rivette on a walking tour of London’s West End prior to the latter film’s world premiere. I certainly can’t claim to have known him well, but no one else I knew during this period did either. He was famously hermitic. With his shy, nervous giggles, he had the manner of a cheerfully enlightened monk. Though he was a familiar presence at the Cinémathèque Française (always occupying the same seat) and was always friendly, he was also a committed solitaire before and after the screenings.

A longtime defender of Rivette, over the years I’ve had occasion to revise some of my positions. I used to maintain that he was one of the major French film critics (together with Godard and the nonwriter Resnais)—which led me to publish a short collection of his criticism in English translation in 1977 (a project undertaken without his official consent, but with his tacit approval)—and that he remained a critic whenever he filmed. This explains why he used other films as critical models—Artists and Models (1955) for Céline and Julie, The Seventh Victim (1943) for Duelle, Moonfleet (1955) for Noroît, Lady in the Lake (1947) for the abandoned Marie et Julien. Yet once it became clear that he was the only member of the Cahiers team to refuse to allow his criticism to be reprinted—mainly, he said, because he no longer agreed with much of it—I began to realize that he had little sense of criticism as a vocation. The lively late interviews he gave to the Parisian weekly Les inrockuptibles, for all their interest, weren’t the musings of a major critic so much as cranky fan-boy arguments. Yet if his movies are themselves a form of film criticism, they are also, as Adrian Martin recently noted in a valuable essay on the director in the online journal Lola, “profoundly psychoanalytic” and quite open to auteurist investigation—but the principal auteur to be illuminated is Rivette himself.

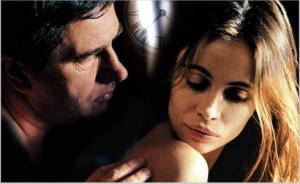

I used to speculate that Rivette’s decision to remove a hair-raising sequence from the thirteen-hour Out 1 before the film was shown on European cable TV—the nervous breakdown of Colin (Jean-Pierre Léaud), alone in his room, in the final episode—was motivated by the director’s concern for the emotional problems of Léaud. I’m now more inclined to believe it stemmed from Rivette’s own identification with the character and his condition. Like the terrifying scene in L’Amour fou in which Sébastien (Jean-Pierre Kalfon) lacerates his clothes and himself with a razor in the midst of a marital crisis, Colin’s collapse was a dovetailing of an actor’s improvisation into something resembling madness. And this contrasts sharply with the way Rivette would handle similar crises in the second part of his career. In La Belle Noiseuse, he calmly explores what the painting of a nude portrait does to the relationships among two couples (painter and wife, model and boyfriend). And later still, the troubled tensions between mortals and goddesses, living and dead characters, that once inflamed such fantasies as Céline and Julie, Duelle, and Noroît are resolved in The Story of Marie and Julien’s unexpected happy ending, in which the couple are reunited.

In both parts of Rivette’s career, the dissolution of a solitary self into a couple or a crew remains a constant. In one of his late interviews in Les Inrockuptibles, he said, “I detest the formulation ‘a film by.’ A film is always [by] at least fifteen people.…Mise-en-scène is a rapport with the actors, and the communal work is set with the first shot. What’s important for me in a film is that it be alive, that it be imbued with presence, which is basically the same thing. And that this presence, inscribed within the film, possesses a form of magic….It’s a collective work, but one wherein there’s a secret, too. “