From the March 31, 2006 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Luc Moullet: Agent Provocateur of the New Wave

Almost 30 years have passed since I wrote a heated article about French filmmaker Luc Moullet for Film Comment — the first extended defense of his movies and his film criticism in English. But the first American retrospective devoted to him is only now opening, at the Gene Siskel Film Center. Only 8 of his 32 films will be included, and some of my favorites are missing. Still, it’s been worth the wait.

Moullet, who grew up in the sticks, the son of a mail sorter and a typist, started writing for Cahiers du Cinéma in the 50s, when he was in his teens, and he’s still a critic today. Brigitte Bardot is seen reading Moullet’s book on Fritz Lang in Godard’s Contempt (1963), and his Politique des Acteurs came out in 1993. But only a fraction of his major writing has been collected. He was the first to write at length about Samuel Fuller and Edgar G. Ulmer and the first at Cahiers to champion Luis Buñuel. Neither a formalist nor an ideologue, he has a particular feeling for film style that in 1958 led him to compare the gratuitous camera movements in Douglas Sirk’s The Tarnished Angels to the run-on sentences in its source novel, William Faulkner’s Pylon. Anticipating his own virtues as a filmmaker, Moullet wrote the following year, “The young American filmmakers have nothing to say, Sam Fuller even less than the others. He has something to do, and he does it, naturally, without forcing it. This isn’t a small compliment.”

And the range of his interests is still impressive: a recent list of favorites includes two silent films by Cecil B. De Mille, a short by Jean-Luc Godard, Rose Troche’s Go Fish, Raul Ruiz’s The Blind Owl, Catherine Breillat’s Tapage Nocturne, and King Vidor’s Ruby Gentry.

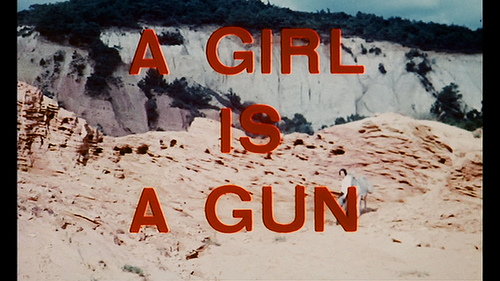

He began making films in the 60s –flaunting his lack of technique and low budgets like a neoprimitive in Brigitte and Brigitte (1966), The Smugglers (1967), A Girl Is a Gun (1971), and Anatomy of a Relationship (1975) and implicitly mocking the glitz of the Hollywood films he wrote about. The title heroines of Brigitte and Brigitte, who hail from separate mountain villages, become roommates in Paris (one of them drops out of English studies at the Sorbonne, just as Moullet did). Their kind of country smarts are important in his films, and mountains are even more so, outclassing Paris as places to roam and pontificate. The plots, insofar as they exist, barely matter. In A Girl Is a Gun — the English-dubbed version of his crazed, erotic Une Aventure de Billy le Kid, with references to Sergio Leone, Anthony Mann, Duel in the Sun, and Buñuel’s L’Age d’Or — the vistas are so breathtaking and the colors so gorgeous they make his meager budget irrelevant. (As an indication of how he’s survived commercially, he sold the rights to this deconstructive bit of dadaism to 40 small countries — presumably on the basis that it was a western starring Jean-Pierre Léaud — though he couldn’t find a French distributor.)

These films reflect some of the tenderness of Françcois Truffaut as well as some of the boorish satirical humor of Godard. Moullet may have thought Fuller had nothing to say, but he himself had plenty, most of it about economy — about the aesthetic advantages of poverty and about a spareness of style and gesture in filmmaking. In his case that poverty and spareness — and his own tenderness and scorn — yielded a cinema of sweet and lovable assholes. Most of the actors in his films are unknowns, but their characters linger warmly in the memory.

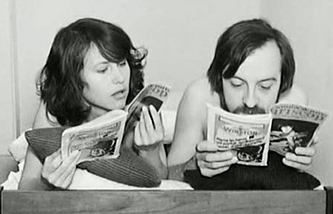

Anatomy of a Relationship–one of the peaks of Moullet’s first period — was made with his partner Antonietta Pizzorno. In it he fearlessly plays himself as he chronicles his and Pizzorno’s awkward sexual problems. (He: “I feel like I’m taking an exam.” She: “I’ll whisper the answers.”) But to complicate matters, Pizzorno doesn’t play herself and appears only at the end of the movie; her part is taken by the lead actress in A Girl Is a Gun.

Not quite a minimalist, Moullet has a way of deflating and mocking pomposity with an earthy, deadpan simplicity. After one of the title heroines in The Smugglers pours a thimble’s worth of rum on a few weeds and lights a match, the narrator solemnly intones, as if in an old-time serial, “The customs officials were met with a wall of fire.”

By the mid-80s Moullet had become a modest master, as a director and as an athletic comic performer with a sense of small moments worthy of Jacques Tati. Opening Tries (1988), the funniest 15 minutes he’s ever filmed, consists of nothing but him trying to open a large bottle of Coke.

The retrospective includes fewer of these later films, and I especially regret the absence of Les Sièges de l’Alcazar, his hilarious 1989 account of a 1956 flirtation between Parisian film critics from rival magazines during a Vittorio Cottafavi retrospective, as well as two shorts from the 90s, one a passionate defense of slag heaps, the other a documentary about Des Moines. I also wouldn’t have minded another chance to see his powerful noncomic documentary Origins of a Meal (1978), which marks the end of his first period, or his exhaustive 1981 documentary about teaching himself to swim. Still, the six features and two shorts being shown here offer a lot. And the polemical force of these strange comedies is especially relevant now, when the low cost of digital cinema is challenging the studios’ oppressive blockbuster mentality.

Significantly, Moullet has produced most of his own films, as well as films by Marguerite Duras and Jean Eustache, and he’s argued that more people should be making more movies for less money: “Each person can realize a good film at least once in his life.” He’s also claimed that if The Smugglers had cost 20 percent less it would have been better “because there would have been something in the film that emphasized this austerity. . . . One of the great advantages of poverty is to develop a sense of responsibility on the part of the director.”

Moullet’s politics can be described roughly as leftist anarchist — Jacques Rivette has called him “our [Alfred] Jarry.” And back in 1958 they were larded with incorrectness. He infuriated some people by declaring, “Fascism is beautiful,” and by celebrating the campy “right-wing” eroticism of films by De Mille, Howard Hughes, Josef von Sternberg, and Vidor. (“It seems that erotic verve is indissociable from contempt for all community, from frantic exaltation of individuality in the pursuit of traditional social and moral principles. . . . That’s the way it is with the two summits of the genre, Jet Pilot and The Fountainhead.”) Godard has usually been credited with the provocative line “Tracking shots are a matter of morality,” implying that stylistic moves have moral consequences, but it’s merely an inversion of something Moullet said four months earlier: “Morality is a matter of tracking shots.” Such statements acknowledge that ethics, politics, erotics, and aesthetics are all closely related, something few people were discussing in relation to Hollywood in the 50s.

Brigitte and Brigitte features both a right-wing and a left-wing Brigitte, and The Comedy of Work (1987) satirizes and admires malingering freeloaders in a welfare state (some of whom are mountain climbers). Both movies are preoccupied with the absurdities of bureaucracy. The 1984 short Barres celebrates the ingenious ways one can get onto the Paris Metro without paying. Most of the squabbles in Shipwrecked on Route D17 (2002) — Moullet’s slickest effort to date, perhaps because he wasn’t the producer — are between city and country people at the beginning of the first gulf war, though he also shows some oafish French soldiers searching the mountains for Saddam Hussein. But the epitome of his deadly, ironic absurdism can be seen in The Smugglers. Over a shot of a rushing mountain stream the narrator says, “Look closely. This used to be a totalitarian state.” The camera pans to the right embankment. “Now it was to know freedom and democracy. All at once, everything would change.” Then it pans back to the same stream. “Look at it now!” The narrator is saying something, and the camera is doing something. And the deed speaks louder than the words.