From the Chicago Reader (January 17, 1992). — J.R.

NAKED LUNCH **** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by David Cronenberg

With Peter Weller, Judy Davis, Ian Holm, Julian Sands, Roy Scheider, Monique Mercure, Michael Zelniker, and Nicholas Campbell.

And some of us are on Different Kicks and that’s a thing out in the open the way I like to see what I eat and vice versa mutatis mutandis as the case may be. Bill’s Naked Lunch Room . . . Step right up. Good for young and old, man and bestial. Nothing like a little snake oil to grease the wheels and get a show on the track Jack. Which side are you on? Fro-Zen Hydraulic? Or you want to take a look around with Honest Bill?” — William S. Burroughs, introduction to Naked Lunch (1962)

The first time I read William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch—or at least large portions of it — was in 1959, a few months after its first printing, in a smuggled copy of the seedy Olympia Press edition fresh from Paris. As I recall it was missing most or all of the accompanying matter — the introduction (“Deposition: Testimony Concerning a Sickness”), “Atrophied Preface” (“Wouldn’t You?”), and appendix (“Letter From a Master Addict to Dangerous Drugs”) — that gave so much body, flavor, shape, and outright usefulness to the Grove Press edition published in the United States three years later. Without this fancy dressing it read like a simple parade of fantasy horrors laced with gallows humor and separated by ellipses, and to my 16-year-old mind it was interesting only for its wild and extravagant obscenities — precisely what had caused it to be banned in the first place.

When I later came to read and reread the American edition the work no longer seemed quite so formless. The introduction provided biographical, moral, and metaphysical focus — the story of Burroughs’s 15-year heroin addiction, and what he called the pyramid of junk and the algebra of need — while the “preface” at the end was full of lovely formal and thematic clues about what Burroughs was up to. Moreover, both sections were written in a powerfully condensed, poetically precise American vernacular that arguably surpassed everything else in the book — in fact they were so pungently written that they placed the entire work in a fresh perspective. (The prosaic appendix, by contrast, was useful mainly in my early experiments with peyote and marijuana, and Burroughs as a reference point on this subject was secondary to the lyrical effusions of other Beat writers, namely Jack Green and Jack Kerouac.)

This second helping of Naked Lunch had such an impact on me that on my first trip to Paris a few years later I snatched up any other Burroughs books I could find, The Ticket That Exploded and Dead Fingers Talk (the second was confiscated by British customs — in those days such a book could be deemed illegal in England before it was published there). During the remainder of the 60s I continued to keep up with Burroughs: Nova Express, The Soft Machine, the American edition of The Ticket That Exploded (also superior to its Olympia forerunner), and many pamphlet-size publications from obscure smaller presses.

But even then my enthusiasm for Burroughs was waning. By the 60s Burroughs had come under the influence of painter Brion Gysin and was fully committed to cut-ups — a technique of arbitrarily folding texts by himself and others and grafting the halves together to see what unexpected meanings flashed out of the jumble. To me this sort of Dada throwback, which usually produced meager results, was only a mechanical means of effecting sudden changes of syntax in mid-sentence, a sort of druggy turnaround that Burroughs had already achieved much more forcefully by instinct in his earlier writing.

These “natural” cut-ups allowed some passages to undergo mysterious sea changes of emphasis and focus in the midst of a monotone patter, and permitted certain similes and metaphors to sprout independent lives and narratives of their own in the course of seemingly logical arguments. Two examples from Naked Lunch, both from the “Atrophied Preface”:

“Sooner or later The Vigilante, The Rube, Lee the Agent, A.J., Clem and Jody the Ergot Twins, Hassan O’Leary the After Birth Tycoon, The Sailor, The Exterminator, Andrew Keif, ‘Fats’ Terminal, Doc Benway, ‘Fingers’ Schafer are subject to say the same thing in the same words to occupy, at that intersection point, the same position in space-time. Using a common vocal apparatus complete with all metabolic appliances that is to be the same person–a most inaccurate way of expressing Recognition: The junky naked in sunlight . . .

You can cut into Naked Lunch at any intersection point. . . . I have written many prefaces. They atrophy and amputate spontaneous like the little toe amputates in a West African disease confined to the Negro race and the passing blonde shows her brass ankle as a manicured toe bounces across the club terrace, retrieved and laid at her feet by her Afghan Hound . . .

What seemed natural and funny in Naked Lunch began to seem forced and abstruse in some of the later books. Furthermore, the relentless misogyny of Burroughs’s writing, coupled with the eventual knowledge that he had killed his own wife, finally got to me, and my ardor for his work went through a distinct cooling-off phase.

Still, I yield to no one in my admiration for the second edition of Naked Lunch. It may not be politically correct, but neither is War and Peace (as Tolstoy, in his subsequent born-again decrepitude, was the first to admit). Neither, for that matter, is David Cronenberg’s highly transgressive and subjective film adaptation of Naked Lunch, which may well be the most troubling and ravishing head movie since Eraserhead. It is also fundamentally a film about writing — even the film about writing, the same one that filmmakers as diverse as Wim Wenders (in Hammett), Philip Kaufman (in Henry & June), and the Coen brothers (in Barton Fink) have been trying with less success to make. Part of what makes it politically incorrect is that it posits an intimate interdependence between the act of creation and the act of murder.

“Heads explode. Parasites fly at people’s faces. Television sets breathe. A woman grows a spike in her armpit and unleashes a cataclysm on the world. These are the startling images David Cronenberg uses to shock and disturb us as his films travel through a nightmare world where the grotesque and the bizarre make our flesh creep.” — jacket copy, The Shape of Rage: The Films of David Cronenberg (1983)

My acquaintance with Cronenberg is much spottier than my acquaintance with Burroughs, and it was made at a relatively late stage in his career. I was impressed but repelled by Scanners when it came out in 1981, but I walked out of a revival of They Came From Within (1975) a few years later, more repulsed than enlightened, and felt pretty neutral about The Dead Zone (1983) and The Fly (1986). It was only three or four years ago, when I caught up with Videodrome (1982) on video (I’ve seen it again at least twice), that I realized just how brilliant Cronenberg is. I didn’t exactly warm to Dead Ringers (1988), but it was such a tour de force that I couldn’t help but think Cronenberg’s craft was growing by leaps and bounds. A subsequent look at The Brood (1979) further persuaded me that his oeuvre has an overall coherence and complexity unmatched by any other contemporary horror director, including David Lynch and George Romero.

All of Cronenberg’s recent works are linked by a style and vision that belong to a particular annex of contemporary art, an annex that might be called biological expressionism. Burroughs is a longtime resident of this annex, and so is his disciple J.G. Ballard; Lynch is the most obvious example of another filmmaker of this persuasion. What all these biological expressionists have in common is a certain deadpan morbidity about the body that borders on comedy — and a tendency to depict paranoia, helplessness, and insect horror in such a way that “inside” and “outside” become indistinguishable.

Dipping into The Shape of Rage (a critical collection published in Canada that is unfortunately no longer in print), I discovered that several other critics had arrived at some of these connections before I did. I learned from a lengthy interview in the same book that Cronenberg, born in 1943 in Toronto, grew up hoping to become a writer, and that Burroughs was a seminal influence, along with Henry Miller, Vladimir Nabokov, and Samuel Beckett. The fact that Cronenberg is Canadian also seems to have shaped his work. Piers Handling, the editor of the collection, speculates that Cronenberg’s “benign but misguided” father figures, who are usually scientists — Dr. Benway (Roy Scheider) in Naked Lunch is a near facsimile — point to a specifically Canadian sensibility, an alienated consciousness that incorporates repression, puritanism, a sense of marginality and victimization, a feeling of entrapment, and perhaps even “a colonized mentality.” (“The land has been exploited but not for the profit of the people who live there.”) Moreover, Handling argues that the fear of external horrors in the first films has been replaced by the fear of internal horrors in all the films subsequent to The Brood, and that the “internalization of this dread achieves its apotheosis in Videodrome.” It’s back again with a vengeance in Naked Lunch.

I was forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing. I live with the constant threat of possession, and a constant need to escape from possession, from Control. So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have no choice except to write my way out. — Burroughs, introduction to Queer (1985)

Perhaps the most transgressive aspect of Cronenberg’s adaptation is that it follows the general approach of some of the very worst movie versions of literary classics — for example, Hemingway’s Adventures of a Young Man and Mishima — by turning what was once fiction into ersatz biography of the author. The vulgar presumption of this approach is that the artist’s life counts for more than the art itself, which is regarded as little more than a symptom. In effect, whatever the artist has done to transform and transcend the banality of his or her own experience is undone by the filmmakers, who turn it back into raw material; by assuming that biography and art are coextensive and virtually interchangeable, they produce works that lack the integrity of either.

On the face of it, this is what Cronenberg has done. He reduces the many protagonists of the book to one, William Lee (Peter Weller), who is clearly meant to be Burroughs himself; indeed, Weller’s fine performance is often little more than an uncanny impersonation. The film opens in New York in 1953, where Lee is working as an exterminator who hangs out with two writers easily recognizable as Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac (Michael Zelniker and Nicholas Campbell), neither of whom appears in recognizable form in the narrative sections of Burroughs’s book. Cronenberg also supplies a drug-addicted wife, Joan (Judy Davis), plainly modeled after Burroughs’s wife Joan Vollmer, who also isn’t in the book. There’s even a fanciful restaging of Burroughs shooting his wife by playing a game of William Tell with her, getting her to balance a drinking glass on her head, firing at it, and missing.

In fact, Burroughs shot his wife in Mexico City in 1951. In 1953 he wasn’t even in New York but traveling about South America looking for the hallucinogenic drug yage; his only stint as an exterminator was in Chicago in 1942, a year or so before he first met Ginsberg and Kerouac in New York. In other words, while the movie is full of references to Burroughs’s life it isn’t really biography at all, and in fairness to Cronenberg it should be added that this is perfectly evident almost from the start — when a gigantic insect starts talking to Lee, enlisting him as an “agent” and giving him orders. It’s rather as if Cronenberg has taken snippets from Naked Lunch, various Burroughs autobiographical texts (chiefly “Exterminator!” and the 1985 introduction to Queer), a few details of Burroughs’s biography, and assorted Burroughs-inspired fancies of his own and placed them all inside a kaleidoscope — or, to switch metaphors, performed an elaborate cut-up with them. Even the film’s haunting and lovely score, which juxtaposes classical themes by Howard Shore with wailing free-form alto-sax solos by Ornette Coleman backed by Coleman’s trio, creates an ambience that is not so much Burroughs as commentary on Burroughs.

What emerges is recognizable but fully transformed Burroughs material. In the film, Lee gets into trouble when he discovers that someone has been stealing his roach powder. His boss, A.J. Cohen, is livid: “You vant I should spit right in your face!? You vant!? You vant!?” This line and Cohen both appear in “Exterminator!” but the missing bug powder is Cronenberg’s addition. When Lee applies to a Chinaman in the office for more powder he gets a curt reply: “No glot. . . . C’lom Fliday.” This line comes from the final words of Naked Lunch, a passage that’s glossed 90 pages earlier: “In 1920s a lot of Chinese pushers around found The West so unreliable, dishonest and wrong, they all packed in, so when an Occidental junky came to score, they say: ‘No glot. . . . C’lom Fliday.'”

Shortly after Lee discovers that his wife has been shooting the missing bug powder and is now addicted, two cops arrest him, take him to a decaying office with vomit green walls, and leave him alone with a gigantic bug who actually gets off on the very substance that is supposed to exterminate it (“Say Bill,” it says, “do you think you could rub some of this powder on my lips?”). The bug orders him to kill his wife, insisting that she’s an “Interzone” agent and not even human. Later, after Joan asks Lee to rub some bug powder on her own lips and they make love, he procures another drug called “black meat” from the sinister Dr. Benway — a drug made from dried “aquatic Brazilian centipedes” that is supposed to get Joan off her habit. But at this point Lee winds up “accidentally” killing her.

Significantly, Lee trades his gun for a portable typewriter at a pawnshop; he then travels to Interzone, a North African city like Tangier where most of the remainder of the film is set. Lee’s “ticket” to Interzone, however, which he shows to one of his writer friends, is the drug-filled syringe procured from Benway, so it’s highly questionable whether Lee or the film ever really leaves New York. (Enslaved by his addiction, he may not even leave his flat.) If one looks closely at certain scenes in Interzone, fragments of New York are plainly visible — a patch of Central Park seen from a window, even an Eighth Avenue subway entrance seen from a car — and at one point Lee remarks that a certain living room reminds him of a New York restaurant. Lee’s flats in New York and Interzone are nearly identical, and he even encounters Kiki (Joseph Scorsiani), who becomes his lover in Interzone, initially in a New York waterfront bar.

Bearing all this in mind, the extreme distortions of Paul and Jane Bowles, fictionalized as Tom and Joan Frost (Ian Holm and Judy Davis) in the Interzone sections, have to be seen as projections of Lee — and beyond that, projections of Cronenberg — rather than as tenable figures having anything to do with literary history or with Burroughs himself. Tom Frost is an older and more overt Lee who acts openly on his desires; Joan is an alternate version of his wife, “addicted” to lesbianism as the other Joan was addicted to bug powder. These characters, as well as Yves Cloquet (Julian Sands), Hans (Robert A. Silverman), and Kiki, show that Cronenberg has taken considerable license in fashioning this world, which clearly has more relationship to his own universe than to Burroughs’s.

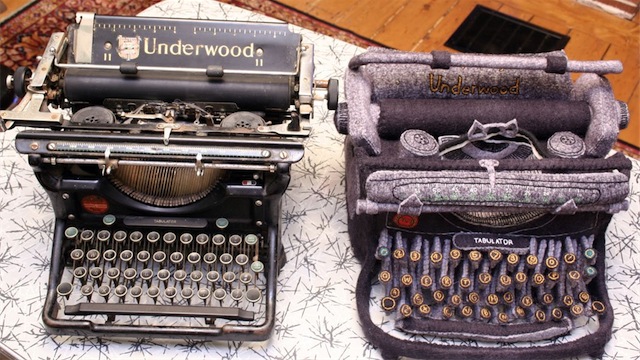

Cronenberg’s method for “adapting” Naked Lunch is roughly analogous to Burroughs’s device of “natural” cut-ups, a process of hallucinatory transformation: roach powder becomes hallucinogenic drug, drug taking becomes sex, roach becomes paranoiac operative, wife becomes insect, and Interzone becomes New York experienced in a drugged state. Later, when Lee becomes a writer in Interzone, the transformations become even more dense and metaphorical: typewriters, for example, become talking cockroaches or Mugwumps (a Burroughs beastie that the film works wonders with, in New York and Interzone alike), functioning variously as Ugly Spirits, muses, prophets, psychiatrists, lovers, friends, bosses, and drug dispensers, so that writing, sex, and drugs become virtually interchangeable. The moment of each transformation, moreover, becomes impossible to pinpoint, because the identities do not strictly mutate but overlap or interface — rather like the colored geometric shapes that traverse the screen in the film’s beautiful opening credits.

Some of these principles of transformation operate formally in a series of short experimental films made in England in the 60s by the late Antony Balch, now available on video, all of them involving Burroughs as writer or actor/performer. (The best are Towers Open Fire and The Cut-Ups.) The transformations here often involve one character assuming the identity of another. A more mainstream, thematic approach to such transformations can be found in two later shorts by Gus Van Sant that are fairly literal adaptations of Burroughs texts: The Discipline of DE (1978) develops from a how-to essay with Zen-like behavioral tips (mainly on housework shortcuts) into a specific fictional illustration, a shoot-out between a Wyatt Earp protege and Two Gun McGee; Thanksgiving Prayer (1991) quickly turns from a counting of American blessings into a parade of all-American horrors. (These shorts are not available on video, but they should be.)

Cronenberg’s approach is neither a strict application of Burroughs’s cut-up principles (as in Balch) nor a straightforward adaptation of his texts (as in Van Sant) but an absorption of certain principles and texts from Burroughs into the filmmaker’s particular cosmology and style. The resulting portrait — and it should be stressed that Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch, unlike Burroughs’s, is a portrait of a single character — is not of Burroughs or Cronenberg but of some mysterious composite, an overlap and/or interface of these two personalities.

[The biographer did not] share Burroughs’s misogyny, which at the bottom was probably an attempt to smother his own contemptible femininity. Born in his hatred of the secret, covered-up part of himself that was maudlin and sentimental and womanly, misogyny was his form of self-loathing.” — Ted Morgan, Literary Outlaw: The Life and Times of William S. Burroughs (1988)

The philosophical parallels between Lynch’s Eraserhead and this film are striking. Both movies are often creepy comedies generated by lurid puritanical imaginations infected by guilt and a will toward censorship, echo chambers of projections and disavowals. When William Lee is “enlisted” as an agent in Interzone, the reports he types up turn out to be Naked Lunch itself, a book he has no recollection of writing. (In his introduction Burroughs said, “I have no precise memory of writing the notes which have now been published under the title Naked Lunch.”) Lee’s homosexuality and his drug taking provoke comparable disavowals, as he projects his desires onto others. Whether he’s engaged in sex, drugs, or writing, Lee can be seen simultaneously as a voyeur and as an active participant in the diverse intrigues and activities of Interzone, which corresponds to the inner zone of his head. Like “innocent” Henry in Eraserhead, he ultimately figures as both progenitor and victim of the diverse horrors surrounding him.

But a key difference between Lynch and Cronenberg corresponds to an equally key difference between Cronenberg and Burroughs. Though Lynch’s vision depends on darkness and cruelty and Burroughs’s more pessimistic and mature vision is tinged with feelings of great loss and sorrow, neither artist can be said to have a tragic vision — as Ballard does, at least in Empire of the Sun. Cronenberg has such a vision, and his Naked Lunch, like Dead Ringers, is suffused with it.

The central tenet in Naked Lunch is that Lee needs his wife in order to live and needs to kill her in order to write, and all the film’s transactions and transformations derive from this appalling fact. He literally has to kill his wife again and again in order to keep on writing, and this condemns him to perpetual psychic imprisonment. (It’s no wonder that by the end of the film Benway, Lee’s bisexual father figure, has enlisted him in the CIA as a secret agent posing as an American journalist, and sent him off to an old-style totalitarian state: Annexia, a Cronenberg invention.) Given Lee’s tragic dilemma, the matching aphorisms that appear at the beginning of the movie resound with irrevocable finality. The first comes from Hassan I Sabbah, an 11th-century Persian religious agitator much admired by Burroughs: “Nothing is true, everything is permitted.” And the second comes from Burroughs himself: “Hustlers of the world, there is one Mark you cannot beat. The Mark inside . . . “