From the Chicago Reader (June 14, 2002). — J.R.

The Believer

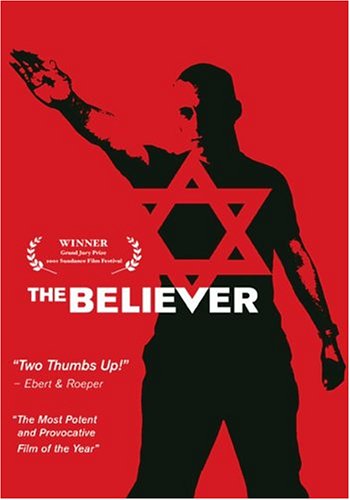

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Henry Bean

Written by Bean and Mark Jacobson

With Ryan Gosling, Summer Phoenix, Theresa Russell, Billy Zane, A.D. Miles, Glenn Fitzgerald, Elizabeth Reaser, and Dean Strober.

The Believer, an independent feature, premiered on cable nearly three months ago, after failing to get a distributor. But it was recently picked up and is opening this week at Landmark’s Century Centre. It’s already created a good deal of buzz, most of it justified.

Inspired by the real-life story of a 28-year-old Jew in Queens named Daniel Burros, who became a high-ranking member of the American Nazi Party and then of the New York chapter of the Ku Klux Klan before fatally shooting himself when the New York Times ran a front-page story revealing that he was a Jew, the film makes a few educated guesses about the possible origins of such a divided identity, yet it’s entirely to the credit of Henry Bean, the writer-director, and Mark Jacobson, who collaborated on the story, that satisfying psychological explanations aren’t what the film is after. As Bean, a Reform Jew, has suggested in various statements, the film is more precisely an exploration of what it means to be Jewish and what it means to hate — two separate subjects that happen to overlap in this case.

Bean’s published screenplay describes him as “a successful screenwriter whose credits include such major motion pictures as Internal Affairs…and Enemy of the State.” For me, Bean’s principal claims to fame are his writing credits on three relatively “minor” and “unsuccessful” but uncommonly good features: Chantal Akerman’s musicals Window Shopping and The Golden 80s (both 1986) and Bill Duke’s political crime thriller Deep Cover (1992), which Bean also produced. Deep Cover was a commercial success, but what it had to say about the hypocrisy of George Bush Sr.’s “war on drugs” was so scathing and accurate that it was mainly ignored by the press (a similarly scathing and accurate picture about George Bush Jr.’s “war on terrorism,” assuming it could be bankrolled and shown, would likely be ignored by the same people today).

What seems especially relevant about Bean’s work with Akerman (he also acted in her 1996 A Couch in New York, released only on cable in this country) is that it belongs to an unpsychological, even antipsychological European tradition founded on a respect for the essential mystery of human personality. This tradition can be traced back at least as far as Catullus — who’s quoted in The Believer‘s opening epigraph: “I hate and I love / Who can tell me why?” — and it contrasts sharply with characteristically American (and post-Freudian) neat psychological explanations for everything, which sometimes seem motivated more by a desire to file away experience than to understand it in any depth. From the opening credits of The Believer, when we hear Danny Balint (powerfully played by Ryan Gosling) as a boy arguing testily in a yeshiva class that the story of Abraham is about God’s power, not Abraham’s faith, while we see him at 22 lifting weights in a room full of books (an image that unavoidably brings to mind Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver), the movie is at pains to contextualize Danny’s troubled Judaism, to place it in a world we can recognize rather than simply attempt to account for it. This classroom discussion and the compulsive weight lifting recur as leitmotivs throughout the film, but neither is posited as any sort of last word on who Danny is.

Just after this opening, while the credits are still fitfully appearing, we see Danny follow and harass a studious-looking Orthodox Jewish youth on the subway and street, finally knocking him down and kicking him while screaming, “Get up! Get the fuck up!…Hit me, hit me — please!” It’s obvious that the victim’s refusal to hit back is what riles Danny the most — no doubt connecting with his anger that Abraham agrees to sacrifice his son Isaac at God’s command rather than protest — but the degree to which Danny’s beef is philosophical rather than simply oedipal is never spelled out. (Over the course of the movie we catch only a few glimpses of Danny with his father at home, all of them brief and unenlightening, and just about the only thing we learn about his mother is that she’s absent.)

Shortly after this incident we see Danny attend a meeting of self-described fascists in the living room of a couple named Curtis Zampf and Lina Moebius (effectively played by Billy Zane, with the laid-back manner of a preppy executive, and Theresa Russell, with a pinched mouth), where he meets Lina’s daughter Carla (Summer Phoenix), a masochist who’s as intrigued by Jews as Danny is obsessed with destroying them (which makes her subsequent sexual involvement with him seem appropriate). Insisting that the modern world is stricken with a Jewish disease that he describes as an obsession with abstraction, Danny proposes killing a few key Jewish figures as a ploy to recruit more fascists, singling out an investment banker and former ambassador to France named Ilio Manzetti (played by Bean himself) as an initial target.

The Nation‘s Stuart Klawans has persuasively compared Danny’s negative obsession with Judaism to the denial of Christianity attempted by Hazel Motes — the tragicomic and absurdist hero of Flannery O’Connor’s first novel, Wise Blood, whom O’Connor conceived as a grotesque parody of existentialists like Sartre and Camus, viewing Motes’s “integrity” as his inability to rid himself of Jesus. It’s certainly true that Danny’s love-hatred for Judaism is made to look increasingly like love as the film progresses, to the point where he even proposes at a subsequent fascist fund-raiser, to the befuddlement and consternation of Lina, that the Jews have to be destroyed with kindness and love, because they’ve already been taught to expect persecution and hatred. “Judaism’s not about belief,” he says to Carla earlier. “It’s about doing things.” Her response to this statement is that he must be Jewish, because Jews are the only ones who talk about Judaism that much. (“You want a punch in the mouth?” he says, to which she replies, “OK” — more evidence that they make a perfect couple.)

Bean described his initial synopsis of The Believer as “a Sam Fullerish tale,” and coincidentally or not, the final film is billed in the opening credits as “A Fuller Films Production.” This is a significant reference not only because of the comprehensive way Fuller dealt with hatred, particularly racial hatred, in his films, but also because Fuller was Jewish — a fact that wasn’t widely known but which struck me as an integral part of his personality when I met him. (The difficulties inherent in being Jewish in many of the milieus he passed through before becoming a filmmaker, especially as a crime reporter, probably account for his reticence, and I wonder how this aspect of his life will be handled in his autobiography, scheduled to come out later this year.)

Fuller also avoided trying to account for racism through psychological profiling, apart from the most obvious kind of conditioning, like that in White Dog — another reason The Believer is Fuller-esque in the best sense, stylistically as well as thematically, drawing on a wide range of expressive possibilities in its use of sound and image. The troubled and troubling sound montage heard over the final credits — music, dialogue, whispers, even the sound of a shofar — is even more suggestive than the juxtapositions at the beginning, because the multiple rhyme effects are ultimately more musical than explanatory, at least in any conclusive way. Danny’s boyhood challenge to God to strike him dead is echoed by his implied suicide as a young adult, though his early anger scarcely accounts for it.