Written as a column for the May-June 1977 Film Comment. Some of the details here are dated, I think, in an interesting manner — especially the discussion of “Disco-Vision”. I should add that the only version of MIKEY AND NICKY that had been released in the mid-70s was an unfinished edit by Elaine May that the studio had taken away from her and put out without her consent. -– J.R.

***

The world had gone crazy, said the crazy man in his cell. What was nutty was that the movie folk were trafficking in illusions in the real world but the real world thought that its reality could only be found in the illusions. Two sets of maniacs.

– Walker Percy, Lancelot

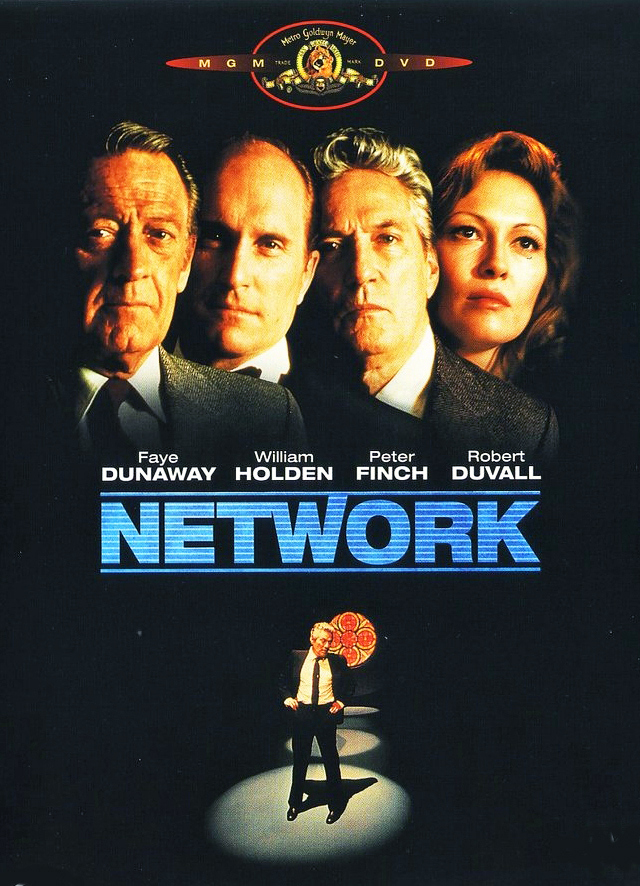

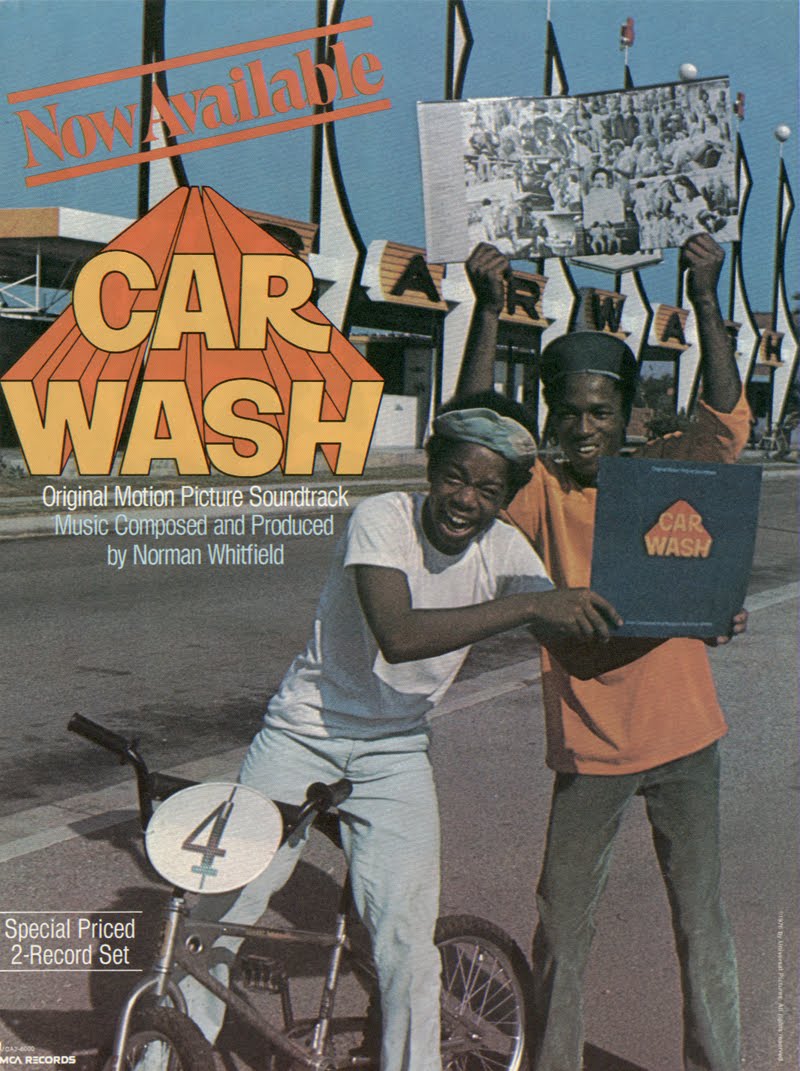

Compare the ads for NETWORK and CARWASH. The former conjures up a hot exposé, a “real” behind-the-scenes glimpse of What Goes On behind the moneyed façade of big-time broadcasting; the latter suggests a frivolous, “irresponsible” fantasy to be seen for fun, not edification. Moving back to the U.S. after over seven years abroad — a sudden shift from reflective Paris chrome and ashen London gray to La Jolla baby-blue, from cinema to some medieval state of pre-cinema or post-Cinema — the foreignness and familiarity of the country both seem epitomized by the absurdity of that cockeyed distinction, which virtually gets it all backwards.

The quasi-fascist cynicism of NETWORK, revealing a contempt for the mass audience that is virtually synonymous with the crassness it professes to attack, situated in a misogynous Cuckooland of swollen middle-aged egos that seems to pre-date even PATTERNS and EXECUTIVE SUITE (Why does Faye Dunaway love William Holden? Because he has the Truth, and she wants It), is accorded acres of space in the press for its “relevance” and “audacity.” (”It’s got Oscar written all over it,” a marquee in Hollywood announces aptly. Oscar Chayevsky?)

Meanwhile, a joyful little “black exploitation” disco-musical that improves on Altman in sheer kaleidoscopic energy, timing, and talent — telling me twice as much about what’s going on without any pretentious flagwaving — gets shafted as an insult to the audience and denied all cultural credentials. Does it take an erstwhile ersatz European to see what’s being ushered out -– and shoveled in? Politically, all you have to do with these films is compare the satiric caricatures of radicals in each one to see how shocking the distance is between them.

One night in downtown Philadelphia last Christmas, I see both movies in a row. The basically black audience at CAR WASH responds at least intermittently in a communal way that suggests mutual recognition — clapping along with the mise en scènethat’s synchronized to the title tune, catching their breath at the editing of the beautifully extended trajectory of the bottle in flight in the silly Mad Bomber episode, and howling with glee when the son of the hysterical matron vomits all over her newly-washed Mercedes. On the other hand, the oblique putdown of the ethics and aesthetics of black capitalism in the Richard Pryor/Daddy Rich sequence, with its subtly integrated photos of JFK and Martin Luther King, causes some restlessness and occasions at least a couple of walkouts. Yet the movie’s sly enough to dissolve the tensions of two other touchy subjects — gayness and radical politics– later in the same scene, when the cartoon queen rebuts the cartoon radical’s insult with, “Honey, I’m more man than you’Il ever be and more woman than you’ll ever get,” winning the audience back in a flash.

Part of the kick of CAR WASH is the way that the white folks are cunningly stereotyped in a kind of reversal of Thirties musicals, often with a wry compassion: when the car wash cashier’s dreamboat comes along, she’s granted a patch of White Muzak on the soundtrack to accord with her own fantasies. The comic book stereotypes of NETWORK are a good deal more autocratic and self-serving; and the audience watching it, predominantly white, reveals a more contradictory mood that suggests narcissistic self-loathing-tittering in mutual disbelief at the hyperbolic dramaturgy, swilling in the outrage of it all with a kind of desperate alienation that seems to love the acid taste of its own body sweat. “I thought it was supposed to be realistic,” I hear someone remark fretfully on the way out, as if voicing a note of post-masturbation regret, reminding me of Michael Arlen’s intriguing column about the film in The New Yorker.

Whether it hinges mainly on writing (Oscar Chayevsky in NETWORK), acting (Sylvester Stallone in ROCKY, who also offers a script reeking of early Chayevsky) or directing (Michael Schultz in CAR WASH), popular American cinema nowadays seems to be involved principally with disgust. Yet movies that try for anything resembling an analysis of that disgust –a MANDINGO, a MIKEY AND NICKY, or even a modest attempt like CAR WASH — get dismissed as garbage by most of the New York press, which lavishes its respect and attention on movies that try to drown the disgust in whippedcream.

***

The interest of seeing three recent mainland Chinese films in London last year — HUNG YU, THE PIONEERS, BREAKING WITH OLD IDEAS — was partially the reminder of what going to the movies used to be like, and which an unexpected delight like CAR WASH dimly recalls: a community event. The real difference, as a Chinese friend points out, is that the exposition of narrative and the exposition of ideology are indistinguishable in these films, and I’m told that when they’re shown in China, audiences talk all the way through them, discussing the “correctness” and “incorrectness” of the ideological points. The whole concept of “comic relief” (as opposed to comedy arising directly from ideology) is as unthinkable in such a context as the notion of “privacy,” which my friend informs me is a term the Chinese language has never had an equivalent for — just as one could search in vain for a French word corresponding to “empathy.”

What this sort of cinema suggests to my jaded Western sensibilities isn’t so much a model as a potential form of analysis — a defining of terms and contexts that Hollywood usually confuses with metaphysics or psychology (under the banner of Realism) in order to keep the market moving. When a movie like MIKEY AND NICKY virtually rules out psychology and deals with brutal social facts (again, under the banner of Realism), the tone is significantly misanthropic, pitiless, bleak, the precise opposite of the indefatigably cheerful humanism and optimism of the Chinese films.

The method of Elaine May’s madness seems almost archaic in relation to the present climate: if THE HEARTBREAK KID was her FOOLISH WIVES, MIKEY AND NICKY must surely be her GREED. But most critics have been shrinking in horror before the abrasiveness of such lucidity, restricting their attention to the scattershot editing, “continuity errors,” and other technical crudities that are undoubtedly there — hung up on technique (correct or incorrect) as much as the Chinese are hung up on ideology — and avoid the social implications of the tightly woven script: a world of middle-class murderers and victims much more ferocious (and no less politically relevant) than anything ever dreamed up by Fassbinder.

***

No longer “based” in a particular geographical location, urban capital, marketing center, distribution outlet, this column will attempt to bypass and challenge these Holy Stations and pursue a more wayward and circuitous route, the kind of path needed to evade all the Heavy Traffic that is clogging up most available escape routes –a direction hopefully leading away from all the president’s last tycoon and godfather networks and into a denser, darker, less colonized forest where the trees don’t even have names yet and the natives speak a language other than Neil Simonese.

***

The best piece of science fiction I’ve I read in ages appears in the January-February Film Comment, where Richard Koszarski describes and speculates about some of the possibilities of Disco-Vision — film discs with numbered (or “paginated”) frames, playable on home sets, reportedly available at $10 each later this Year.

Does this mean the end of the Film Industry as we know it in another decade or so, with a few more croaking KONGs to bleat out the final death knell? And could it mark the true. beginning of film study and film criticism, now so cut off from its sources, when everyone has his or her own text to cite (”cf. frames 9163-9909, op. cit.“) and can graze over any section at will?

***

The first indication I had that Alain Resnais’ PROVIDENCE might be something special — apart from the enthusiasm of the French press — was the report that most Manhattan critics hated it. (The wittiest crack I hear about describes it as “his most puerile film since GUERNICA.”) I’m fully persuaded that even if a better Resnais movie — like MURIEL — opened in New York today, it wouldn’t get an adequate defense from anyone.

New York in late February: The very notion of. film history has shrunk so alarmingly that the most constricted sort of contexts can be accepted without question. Explaining why she walked out of CASANOVA, Pauline Kael can write that “Fellini has done something no one else in screen history has done: he has made an epic out of his own alienation,” which neatly wipes IVAN THE TERRIBLE and a great deal more out of the history books — not to mention Jacques Rivette’s NOROÎT, which one can safely bet that Kael will never see. Does this mean that, with the help of Disco-Vision, we can all look forward to close textual analyses of CARRIE and Gulf + Western’s KING KONG, subjected to precise materialist readings at variable speeds? The sense of a continuous present in New York is becoming increasingly impoverished.

***

Paris in early February: Seeing PROVIDENCE on two successive nights in a large, crowded Left Bank cinema, I’m part of an enrapt audience, and both times there’s applause at the end. Can this really be accounted for by the hypothesis of a New York colleague — that the audience doesn’t understand the subtitled English? I don’t think so. Even if one can’t accept David Mercer’s self-conscious, middlebrow, English-theatre script as a fair rendering of the mind of John Gielgud’s self-conscious, middle-brow English novelist, it’s still a damn sight better written than most reviews I’ve read of PROVIDENCE. And there’s a lot more to the movie than the script: directed by anyone else, it might not have been worth the bother.

The irony is that PROVIDENCE is a warm, old-fashioned realist film, made with a kind of clout that has long since vanished from Hollywood. To see reality as a form of Lovecraftian enchantment filtered through a writer’s rambling emotions and imagination isn’t a very radical thing to be doing in the mjd-Seventies, and I’d be the last to claim that Resnais is onto anything innovative. I’m simply grateful for his demonstration of movie magic at a time when the standard upholstery of most film fiction has become astonishingly meager (cf. any frame from THE LAST TYCOON & Co., op. cit.)

To enjoy the film, of course, you have to believe that reality is constructed rather than given, and intuited rather than grasped — in the luminous final sequence no less than in the others’ All Resnais’ films are about the inexpressible, but the moving sweetness of PROVIDENCE is that while all the successive incarnations and versions of Dirk Bogarde, Elen Burstyn, Elaine Stritch, and David Warner are equally idealized and “unreal,” their collective resonances compose, along with Gielgud, the five most solid characters in any film I’ve seen this year –- phantoms perceived, like all “real” people, through the intimate biases of the mind. In this respect, they resemble the haunted Tyrones in Long Day’s Journey into Night. Finely turned in a way that exposes such creations as StalIone’s Rocky or Bergman’s SCENES FROM A MARRIAGE couple as stereotypes cut from the crudest cardboard, they project a mysterious density through Resnais’ poetic mélange of props and places that his musically measured editing contrives to convey, not unravel. Thus the 360-degree crane around a gorgeous landscape in the last scene, taking in the breadth of a supposedly material and ordered world, is as pregnant with wonder and latent meaning as the beautiful earlier image of a werewolf in a wheelchair being lifted into an ambulance.

“The cinema is necessarily fascination and rape, that is how it acts on people,” Rivette remarked in 1968 (in a Cahiers interview included in a small collection of his criticism and interviews that I recently edited for the British Film Institute); “it is something pretty unclear, something one sees shrouded in darkness, where you project the same things as in dreams. . . .” I doubt that any more than half of me believes in this today; the other half is more prone to root out the mysteries and curse the darkness. But for the dark side of me, I can’t think of any recent movie quite as ravishing as PROVIDENCE.

Published on 06 Apr 2013 in Notes, by jrosenbaum