From the December 15, 2000 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

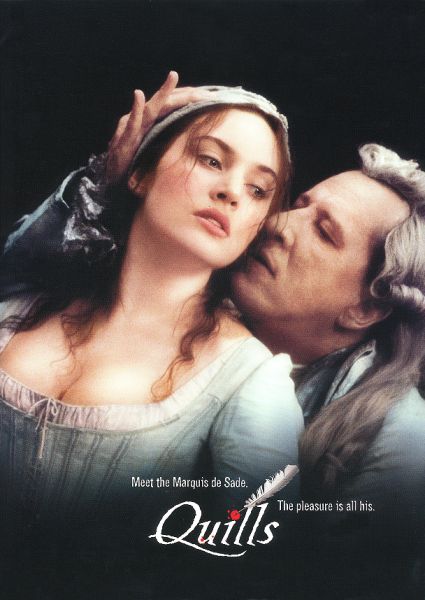

Quills

***

Directed by Philip Kaufman

Written by Doug Wright

With Geoffrey Rush, Kate Winslet, Joaquin Phoenix, Michael Caine, Billie Whitelaw, Patrick Malahide, and Amelia Warner.

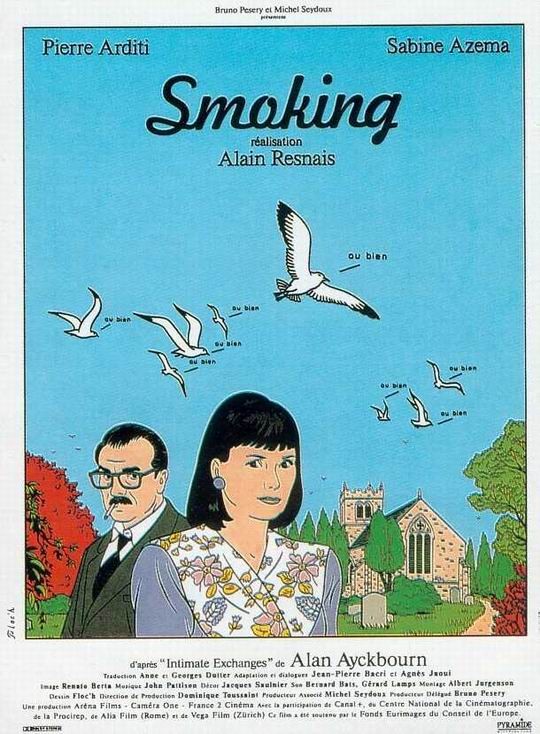

Smoking

***

Directed by Alain Resnais

Written by Alan Ayckbourn, Jean-Pierre Bacri, Agnès Jaoui, and Anne and Georges Dutter

With Pierre Arditi and Sabine Azéma.

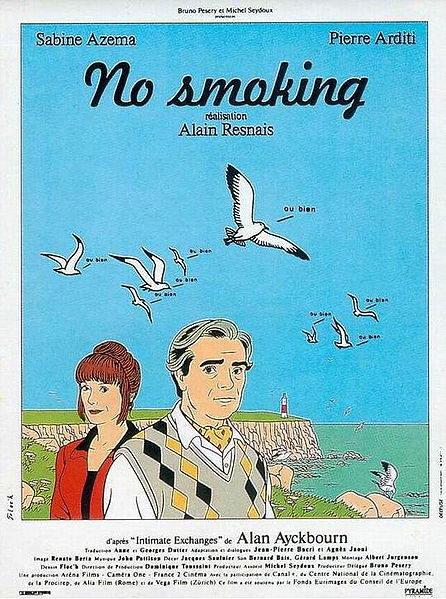

No Smoking

***

Directed by Alain Resnais

Written by Alan Ayckbourn, Jean-Pierre Bacri, Agnes Jaoui, and Anne and Georges Dutter

With Pierre Arditi and Sabine Azema.

Quills is an American adaptation of an American play about the famous 18th-century French libertine the Marquis de Sade, starring Australian, English, and American actors. It is also, in part, an unacknowledged mainstreaming of a more intellectual German play that became famous in the mid-1960s because of an exciting and inventive staging by avant-garde English director Peter Brook — Peter Weiss’s The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, popularly known as Marat/Sade. (Brook’s 1966 film adaptation of this intensely theatrical play is a pale shadow of the original.)

Smoking and No Smoking — not a double bill but a pair of interactive features that can be seen in either order, both playing at Facets Multimedia Center this week — are French adaptations of a cycle of eight mainly comic English plays by Alan Ayckbourn. Read more