From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1995). — J.R.

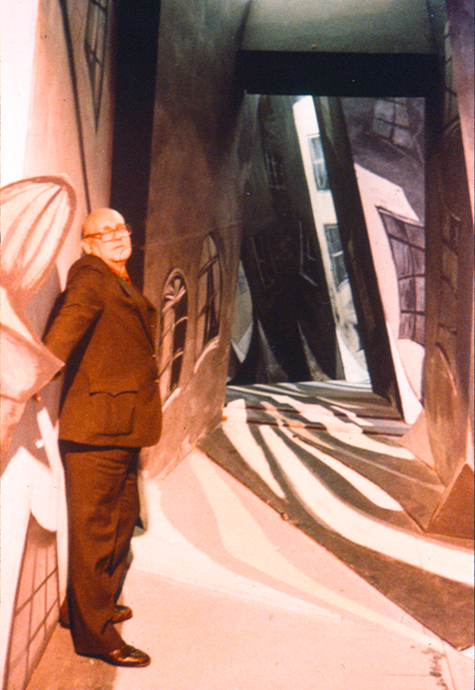

After the success of Rain Man Barry Levinson was allowed to indulge himself with Toys, and after Cinema Paradiso Giuseppe Tornatore was similarly allowed to foist this work of staggering pretentiousness on the public (1994). This French-Italian production with French dialogue, written with Pascale Quignard, starts off promisingly enough as a police thriller with metaphysical and symbolic overtones, but becomes steadily more abstract and preposterous as it gets closer to the denouement. A man without identity papers (Gerard Depardieu) running through the woods in a raging storm in an unnamed country is arrested and taken to a dilapidated police station to be interrogated. He claims to be a famous writer named Onoff, but the facts he offers the inspector (Roman Polanski) are confused and contradictory, and as the night wears on things just get murkier and murkier. The performances by the two leads and by Sergio Rubini are more than serviceable, but it makes little difference given that the material is so gratingly awful. Beware. (JR)