After Jacques Rivette’s 750-minute comic serial Out 1 (1971) was turned down by French state TV, Rivette spent most of a year editing the material into this scary 255-minute masterpiece—not so much a digest as a different film with its own style and rhythms. Spectre (1972) tells the same basic story about two Parisian theater groups preparing Aeschylus plays and two eccentric loners, a middle-class deaf-mute (Jean-Pierre Leaud) and a working-class flirt (Juliet Berto), who stumble upon evidence of a secret group that hopes to control Paris. The actors created their own characters and dialogue; what emerges is a strange mix of bravura acting styles, an unforgettable evocation of the period, and a haunting puzzle. With Francoise Fabian, Bernadette Lafont, Michel Lonsdale, and Bulle Ogier. In French with subtitles. Showing in a 35-millimeter restoration with a 15-minute intermission. Sat 6/9, 3 PM, Gene Siskel Film Center. Read more

Down To Earth

My favorite Pedro Costa feature to date, an inviting “Open, sesame” to all his work, is his second (1994), a very personal remake of Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked With a Zombie (1943). It follows an obscurely motivated Lisbon nurse (Ines de Medeiros) accompanying a construction worker in a coma (Isaach de Bankolé) back to his native village, on a spectacular volcanic island in Cape Verde, once a hub of the slave trade. (The film’s original and much better title is “Casa de Lava,” or “House of Lava”). While she waits for him to wake she gets to know some of the villagers, including another European (the terrific Edith Scob) who unlike her has succeeded in going native. Gorgeously shot, with fabulous Creole music, this mysterious and voluptuous spiritual adventure has afforded me far more pleasure than any new film I’ve seen this year. In Portuguese and Creole with subtitles. 110 min.

Appendix from FILM: THE FRONT LINE 1983 (part three)

My book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver: Arden Press), intended by its editor-publisher to launch an annual series, regrettably lasted for only one other volume, by David Ehrenstein, after two other commissioned authors failed to submit completed manuscripts. Miraculously, however, this book remained in print for roughly 35 years, and now that it’s finally reached the end of that run (although some copies can still be found online), I’ve decided to reproduce more of its contents on this site, along with links and (when available) illustrations. I’m beginning with the book’s end, an Appendix subtitled “22 More Filmmakers,” which I’m posting here in three installments, along with links and (when available) illustrations. — J.R.

MAURIZIO NICHETTI is a name I happen to know strictly by chance. My last trip to Europe (and only trip to Italy) consisted of three days at the Venice Film Festival in 1979, where I was invited to participate in a conference devoted to Cinema in the Eighties. And as I noted in an account of that conference in the December 1979 American Film, one film that I happened to see during those three days, Maurizio Nichetti’s Ratataplan — a first feature with an onomatopoeic title based on the sound of a drum cadence — may have actually suggested more about the subject of the conference than any of the lectures I heard. Read more

Appendix from FILM: THE FRONT LINE 1983 (part two)

My book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver: Arden Press), intended by its editor-publisher to launch an annual series, regrettably lasted for only one other volume, by David Ehrenstein, after two other commissioned authors failed to submit completed manuscripts. Miraculously, however, this book remained in print for roughly 35 years, and now that it’s finally reached the end of that run (although some copies can still be found online), I’ve decided to reproduce more of its contents on this site, along with links and (when available) illustrations. I’m beginning with the book’s end, an Appendix subtitled “22 More Filmmakers,” which I’m posting here in three installments, along with links and (when available) illustrations. — J.R.

PAULA GLADSTONE. In Gladstone’s mainly black-and-white, hour-long, Super-8 The Dancing Soul of the Walking People (1978), possession and. dispossession both happily become very much beside the point. Shot over a two-year period, 1974-1976, each time the filmmaker went home to Coney Island (“I’d take my camera out and walk from one end of the land to the other,” she reports in Camera Obscura [No. 6]; “I’d talk to people on the streets and film them”), The Dancing Soul of the Walking People is basically concerned with the space underneath a boardwalk, a little bit like the luminous insides of a translucent zebra on a sunny day — an interesting kind of space, at once public and private, that is traversed by receding strips of light, camera pans, and people, in fairly continuous processions and/or rhythmic patterns. Read more

Appendix from FILM: THE FRONT LINE 1983 (part one)

My book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver: Arden Press), intended by its editor-publisher to launch an annual series, regrettably lasted for only one other volume, by David Ehrenstein, after two other commissioned authors failed to submit completed manuscripts. Miraculously, however, this book remained in print for roughly 35 years, and now that it’s finally reached the end of that run (although some copies can still be found online), I’ve decided to reproduce more of its contents on this site, along with links and (when available) illustrations. I’ll begin with the book’s end, an Appendix subtitled “22 More Filmmakers,” which I’ll post here in three installments, along with links and (when available) illustrations. — J.R.

APPENDIX: 22 MORE FILMMAKERS

All sorts of determinations have led to the choices of the individual subjects of the 18 previous sections — some of which are rational and thus can be rationalized, and some of which are irrational and thus can’t be. To say that I could have just as easily picked 18 other filmmakers would be accurate only if I had equal access to the films of every candidate. Yet some of the arbitrariness of the final selection — particularly in relation to the vicissitudes of American distribution and other kinds of information flow — has to be recognized. Read more

Recommended Reading: THE INVISIBLE DRAGON, revised & expanded edition

THE INVISIBLE DRAGON: ESSAYS ON BEAUTY (revised and expanded edition) by Dave Hickey (Chicago/London: The University of Chicago Press), 2009, 123 pp.

Fellow fans of art critic Dave Hickey should be alerted to the fact that an extensively upgraded edition of his 1993 book The Invisible Dragon has recently appeared that seems to be almost twice as long as its predecessor, with a new introduction and an additional essay, “American Beauty,” that’s considerably longer (over 50 pages) than any of the four essays in the first edition. Even if you find the new introduction, written entirely in the third person, a mite off-putting, the new essay reaffirms Hickey as a major critical voice and terrific prose stylist. I’m not sufficiently well-versed in art history to be able to judge it confidently on those terms, but the erudition on display is pretty daunting, to say the least.

I discovered Hickey thanks to film scholar Dudley Andrew through Hickey’s extraordinary 1997 collection Air Guitar (see below) a radically populist and semiautobiographical look at pop culture that remains a particular favorite–although I subsequently bought Hickey’s two collections of short stories, the 1989 Prior Convictions and the 1999 Stardumb, that I’m still intending to read. Read more

La Commune (paris, 1871)

Peter Watkins’s 1999 made-for-TV film about the revolutionary Paris Commune formed in 1871 offers a stunning lesson in understanding the past in relation to the present. Using contemporary talk-show and TV-news reporting techniques, Watkins shot the 345-minute film in only 13 days in an abandoned Paris factory. His cast consisted of 220 Parisians and illegal aliens from North Africa, most of whom had no acting experience, and he got them to do their own research on the Paris Commune and to collaborate in the construction of their characters and dialogue (in late scenes these actors, still in costume, discuss the relevance of the Commune to their own lives and contemporary issues). In some ways this work is more fascinating as an idea than in its execution. But it’s full of exciting moments and very effectively shot, in black and white and with extended mobile takes. In French with subtitles. (JR) Read more

Ellipses, Reels 1-4

My exposure to Stan Brakhage’s massive oeuvre has been somewhat limited, but these four works made in 1998 are among the most exciting and ravishing I’ve seen, rivaling even Scenes From Under Childhood (1970). Aptly described by J. Hoberman of the Village Voice as scratch-and-stain films, these mainly nonphotographic works are, among other things, a visual analogue to Abstract Expressionism. Reel 1 (22 min.) registers as visual music in its development of motifs and its use of rests to divide the work into discrete sections-a music that pulses, throbs, and sometimes winks on and off like a strobe light. Reel 2 (15 min.) credits Sam Bush as the visual musician and Brakhage as the composer; more staccato, dramatic, and richly orchestrated than the first reel, it occasionally recalls early Stravinsky in its fierce rhythms. Reels 3 (15 min.) and 4 (20 min.) are my favorites: the former uses bursts of photography (water, sky, birds, forest, sand, a nude child, merry-go-round horses), and the latter often suggests animation, with a black field disrupted by tantalizing bursts and smears of color. Also on the program are two Brakhage works I haven’t seenCoupling (1999, 5 min.) and Night Mulch & Very (2001, 7 min.). Read more

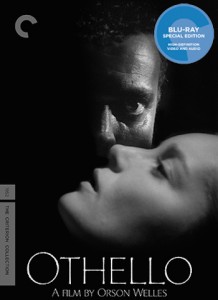

My Best Blu-Rays List for DVD Beaver, 2017 (the long version)

A much shorter version of this was just posted by DVD Beaver:

Top Blu-ray Releases of 2017:

1. Othello (Orson Welles, 1952) Criterion Collection

2.Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project No. 2 (Limite — Mário Peixoto, Revenge — Ermek Shinarbaev, Insiang — Lino Brocka, Mysterious Object at Noon — Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Law of the Border — Lütfi Ö. Akad, Taipei Story — Edward Yang) — Criterion Collection

3. Vampir Cuadecuc (Pere Portabella, 1971) UK Second Run Features

4. The 4 Marx Brothers at Paramount (The Cocoanuts, Animal Crackers, Monkey Business, Horse Feathers, Duck Soup) (1929-1933) RB Arrow UK

5. Anatahan (Josef von Sternberg, 1953) Kino

6. A Brighter Summer Day (Edward Yang, 1991) RB Criterion UK

7. Moses and Aaron (Danièle Huillet, Jean-Marie Straub, 1973) Grasshopper Film

8. Letter from an Unknown Woman (Max Ophüls, 1948) Olive Signature

9. Lost in Paris (Dominique Abel, Fiona Gordon, 2016) Oscilloscope Pictures

10. A New Leaf (Elaine May, 1971) Olive Signature

A major reason for listing Criterion’s Othello first is that it includes the digital premieres of not one and not two but three Orson Welles features: both of his edits of Othello available with his own soundtracks, heard for the first time in the U.S. Read more

SUSPENSE on Ice

Written for Lola no. 7, posted in November 2016. — J.R.

Suspense on Ice

An ice-skating noir musical? More or less, with Belita serving as Monogram’s answer to Sonja Henie, and a few A-picture production numbers (such as the Daliesque one glimpsed above, climaxing with the heroine diving through a wheel ringed by long, sharp daggers pointed towards the center). Not quite a two-dollar movie (the Warners Archive DVD is pricier), but an intriguing curiosity. Philip Yordan’s original script is so pro forma that one can almost imagine him writing it in his sleep, In its early stretches, it suggests a lazy rip-off of Gilda, with different sexual inflections (no homoerotic undertones, no heterosexual love-hatred, and this time the hero and villain are the same character, played by Barry Sullivan), Yet most of it was shot at the same time as Gilda, in late 1945.

Most curious of all is the almost total lack of motivation whereby Sullivan, a thuggish tramp, gets accorded a free white coat and shave by the owner of The Ice Parade so that he can sell peanuts to the customers, and then, after dreaming up the wheel-of-dagger stunt, which Belita accepts without hesitation, gets asked by her husband-boss (Albert Dekker) to take over his position when he leaves on a trip, allowing Sullivan more of a chance to romance his beloved spouse and star. Read more

Philosophical Treatises of a Master Illusionist: A Conversation about Abbas Kiarostami

This is a slightly different edit of a dialogue proposed and inaugurated by Ehsan Khoshbakht on July 5, 2016, edited by him, and published in the British Council’s online Underline magazine on July 8. — J.R.

Abbas Kiarostami (1940-2016), arguably the greatest of Iranian filmmakers, was a master of interruption and reduction in cinema. He, who passed away on Monday in a Paris hospital, diverted cinema from its course more than once. From his experimental children’s films to deconstructing the meaning of documentary and fiction, to digital experimentation, every move brought him new admirers and cost him some of his old ones. Kiarostami provided a style, a film language, with a valid grammar of its own. On the occasion of this great loss, Jonathan Rosenbaum and I discussed some aspects of Kiarostami’s world. Jonathan, the former chief film critic at Chicago Reader, is the co-author (with Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa) of a book on Kiarostami, available from the University of Illinois Press. – Ehsan Khoshbakht

Ehsan Khoshbakht: Abbas Kiarostami’s impact on Iranian cinema was so colossal that it almost swallowed up everything before it, and to a certain extent after it. For better or worse, Iranian cinema was equated with Abbas Kiarostami. Read more

Global Discoveries on DVD: Extras, Promos, Prices

From Cinema Scope issue 39, Summer 2014. — J.R.

I shelled out $56.19 in US dollars (including postage) to acquire the definitive and restored, director-approved DVD of Providence (1977) from French Amazon, and I hasten to add that this was money well spent. Notwithstanding the passion and brilliance of Alain Resnais’ first two features, Providence is in many ways my favourite of his longer works, quite apart from the fact that it’s the only one in English. And I can’t ascribe this preference simply to the contribution of David Mercer (1928-1980). I recently resaw the only other Mercer-scripted film I’m familiar with, Karel Reisz’s Morgan!, and aside from the wit of its own sarcastic dialogue I mainly found it just as flat and tiresome as I did in 1966, for reasons that are well expounded in Dwight Macdonald’s contemporary review (reprinted in his collection On Movies).

I haven’t yet been able to see The Life of Riley (Aimer, boire et chanter), Resnais’ swan song, but clearly part of what gives Providence even more resonance now, writing less than a month after Resnais’ death, is the theme it shares with his penultimate feature, You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet (2013): an old writer facing his own death, and trying to create some form of art in relation to it. Read more

Two Death Scenes of Jean-Pierre Léaud

Commissioned by MUBI (I forget when).

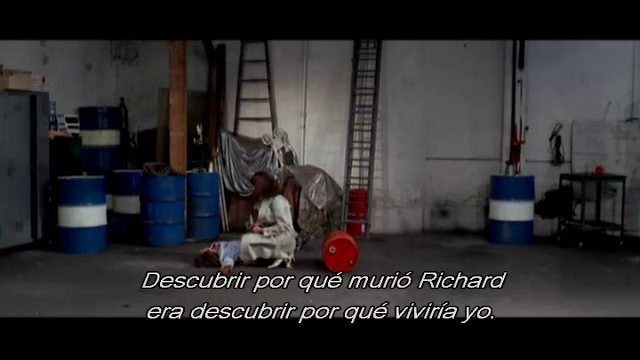

Given the size and variety of Jean-Pierre Léaud’s filmography,

there must be other memorable death scenes of his apart

from those in Jean-Luc Godard’s Made in USA (1966) and

Albert Serra’s La mort de Louis XIV (2016), half a century

apart. My reason for settling on these two is that they

demonstrate his prodigious range. In the first — a very bizarre

piece of anamorphic Pop Art self-described as “a political film,

meaning Walt Disney plus blood” — he plays “Donald Siegel”,

the abused sidekick of gangster “Richard Widmark” (Laszlo

Szabo), comically sporting a button that declares “Kiss me I’m

Italian”. He’s dispatched in a garage by Paula Nelson (Anna

Karina), a detective investigating her lover’s murder. After

Siegel pantomimes committing murders of his own and other

criminal adventures as they’re being recounted by Nelson in

voiceover, she asks him, “If you had to die, would you rather

be warned or die suddenly?” He selects the latter and as soon

as she obligingly plugs him, he shouts out “Mama!” and staggers

extravagantly in long shot across most of the garage floor before

finally expiring. It all takes a little over twelve seconds, whereas the

less showy, more minimalistic and iconic finale as the eponymous

Louis XIV, shown mainly in regal close-ups, lasts for virtually all of

the film’s 116 minutes. –Jonathan Read more

An Epic of Understanding: John Gianvito’s WAKE (SUBIC)

Posted on Film Comment‘s blog, February 2, 2016. — J.R.

Consider the lengths of time between Jean Vigo’s death and the first appearances of Zéro de conduite and L’Atalante in the U.S. (thirteen years), or between the first screening of Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 and its recent appearances on Blu-Ray (forty-five years), and it becomes obvious that the popular custom of listing the best films of any given year is unavoidably a mythological undertaking. By the same token, film history in the present should be divided between important filmmakers skilled and successful in hawking their own goods, from Alfred Hitchcock to Spike Lee to Lars von Trier, and those who, for one reason or another, aren’t — a less definitive roll call that includes, among many others, Charles Burnett, Ebrahim Golestan, Luc Moullet, Peter Thompson, Orson Welles, and John Gianvito.

I haven’t seen Gianvito’s early shorts, one of which is called What Nobody Saw (1990), but its very title seems emblematic of his career — as does the epigraph from Cesare Pavese opening the first part of his first feature, The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001), which introduced me to his work and remains my favorite: “Everywhere there is a pool of blood that we step into without knowing it.” Read more

EXCHANGE WITH JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

An email interview with Federico Casal in June 2017 for the online Uruguayan film magazine Revista Film. Casal has kindly provided me with this English version. — J.R.

EXCHANGE WITH JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

“I miss the experience of communal and theatrical filmgoing.”

Jonathan Rosenbaum (born February 27, 1943 in Alabama, United States) is an American film critic with more than 50 years of experience. He has written thousands of articles and reviews, as the head critic of the Chicago Reader between 1987 and 2008, and collaborator in The Village Voice, Film Comment, Sight & Sound, Cahiers du Cinéma, Trafic, Film Quarterly, Criterion Collection, among others. He studied literature at Bard College in New York—there he met his most influential teacher, Heinrich Blücher, the German philosopher and second husband of Hanna Arendt. In 1969 he moved to Paris, shortly after which he became Jacques Tati’s assistant for a while and appeared as an extra in Robert Bresson’s Four nights of a dreamer (1971). From Paris he moved to London and then to California. Currently, he lives in Chicago. He has published numerous books on cinema, most recently Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia, Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Cannons and Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See, and others about Orson Wells, Jacques Rivette and Abbas Kiarostami. Read more