This appeared in the May 1, 2008 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Last Year at Marienbad ****

DIRECTED BY ALAIN RESNAIS

WRITTEN BY ALAIN ROBBE-GRILLET

WITH GIORGIO ALBERTAZZI, DELPHINE SEYRIG, AND SACHA PITOEFF

It’s too bad Last Year at Marienbad was the most fashionable art-house movie of 1961-’62, because as a result it’s been maligned and misunderstood ever since. The chic allure of Alain Resnais’ second feature — a maddening, scintillating puzzle set in glitzy surroundings — produced a backlash, and one reason its defenders and detractors tend to be equally misguided is that both respond to the controversy rather than to the film itself.

“I am now quite prepared to claim that Marienbad is the greatest film ever made, and to pity those who cannot see this,” proclaimed one French critic, even as others ridiculed what they perceived as the film’s pretentious solemnity — overlooking or missing its playful, if poker-faced, use of parody as well as its outright scariness. Dwight Macdonald, who admitted to seeing the movie three times in a week, confessed in Esquire that it made him feel like a dog in one of Pavlov’s experiments. In the Village Voice, on the other hand, Jonas Mekas claimed that “the film begins and ends in the brain of Alain Robbe-Grillet, who wrote the script” and added, “Its forced intellectualism is sick.” A few years later Noel Burch noted aptly, if unkindly, “There will always be an 8½ to serve as a refuge for those who are frightened by the prospects revealed by a Marienbad.”

Part of what might frighten a Fellini fan was Marienbad’s formalism, as well as its mysterious, obsessional mood. But who could even describe what was happening on-screen? Sight and Sound’s Penelope Houston came the closest: “The opening is entirely hypnotic. Like the beginning of a fairy tale, it draws us into an alien world, gives us no chance to get our bearings, hints at clues which may or may not turn out to have meaning. Slowly, through a mosaic of images and fragments of dialogue, flashes of single figures, static groups, conversation pieces, all framed with the heavy theatricality of the setting, the theme of the film begins to crystallize.”

Beautifully shot in black-and-white CinemaScope and set in an opulent rural hotel (or more likely several, dovetailed into a single labyrinthine set of interconnecting spaces), the movie centers on three upper-crust characters in formal or semiformal attire, identified in the script only as X, A, and M. X, the Italian narrator (Giorgio Albertazzi), tries to convince French fashion-plate A (Delphine Seyrig) that they’d met the previous year and had agreed to run away together upon meeting again this year, leaving behind A’s French husband, lover, and/or guardian, M (Sacha Pitoeff). All this could be real or imaginary, as perceived or fantasized by X or A — or us — in some indeterminate past, present, future, or conditional time.

Contributing to the confusion was Robbe-Grillet’s ponderous rhetoric, both in his high-flown, radical theories about the “new novel” (of which Marienbad was meant to be a prime illustration) and in X’s incantatory narration. In interviews they gave together, he and Resnais seemed to agree that their movie was about mental reality (without specifying whose) and persuasion. But their interpretations, including even their senses of the plot’s outcome, otherwise differed. For Resnais, X’s power over A was persuasive, a form of seduction; for Robbe-Grillet, it was basically rape. In his published screenplay, Robbe-Grillet even included a rape scene that Resnais refused to film, substituting a startling succession of overlit, subjective camera movements rushing repeatedly into A’s welcoming arms.

I saw this lush experimental movie at least three times the week it opened at the Carnegie Hall Cinema, when I was a college sophomore, and was as smitten as anyone. I still am. But I don’t think Marienbad’s effect on me would have been as powerful if I hadn’t spent most of my childhood soaking up commercial movies, just as Resnais did. Hollywood and its French counterparts are at the center of the movie’s glamour and beguilement, as well as its tricky mind games. If you watch closely you’ll catch a glimpse of a life-size blowup of Alfred Hitchcock [see above], eavesdropping on hotel guests beside an elevator, shortly before X makes his first on-screen appearance. Quite a bit later, when M is with A in her bedroom, Resnais’ sequence of shots alludes to a scene between Rita Hayworth and George Macready in Gilda. A’s Chanel dresses (including one made of feathers) evoke Marlene Dietrich in her Josef von Sternberg movies, and no less evident is the ambience of silent French high-society crime serials like Fantomas and Les Vampires.

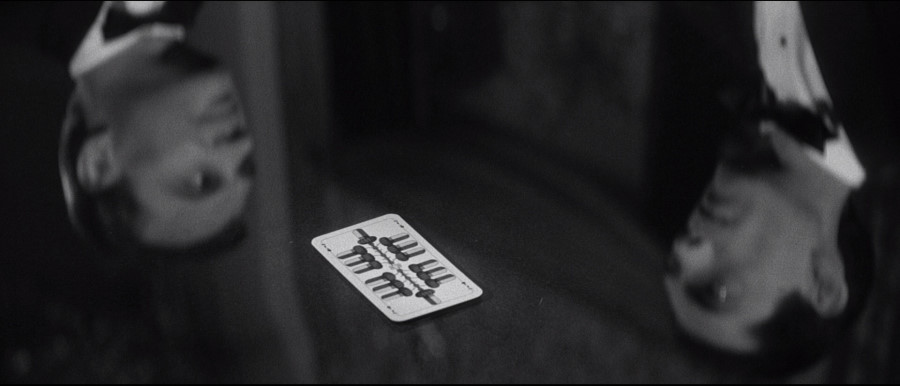

When X illogically appears twice within the same tracking shot — first seen playing cards with M and others, then approaching A, who’s been watching the game at a distance and from behind — the effect may be nightmarish, but it’s also not too different from a vaudeville gag in The Band Wagon, featuring Oscar Levant at both ends of a ladder. Even an allegorical game with matchsticks played repeatedly by X and M — a kind of puzzle within a puzzle — suggests the showdowns between heroes and villains in some westerns. Yet we’re never nudged to laugh at the campiness; Resnais never tampers with the film’s purity as a voluptuous experience.

Both Resnais and Robbe-Grillet were born in 1922, and shared a set of cultural references. (Though Marienbad’s settings and costumes confound any precise sense of period, the era of their youth — evoked so memorably in Resnais’ 1986 Mélo — seems to dominate.) The biggest difference between the two men may have been their sexual sensibilities. Robbe-Grillet’s preoccupation with bondage and domination — which earned him the jokey epithet metteur-en-chaine (“placer in chains”) and turned his late novels into programmatic porn thrillers — placed him closer to the aggressive X, while Resnais was clearly more in sympathy with A (and would use Seyrig again, no less memorably, in his next feature, Muriel).

The film is certainly about a battle of wills, but whether X or A comes out on top is far from certain. In Houston’s description, “fairy tale” is the crucial term, and Freudian resonances are never far away. What many have called cerebral in Marienbad is revealed to be highly emotional once one surrenders to the film’s dreamlike rhythms and sensual surfaces, its sudden, uncanny transitions, its rude shocks. And the haunting aftertaste is no less primal: “The film’s last shot is of the great chateau,” Houston noted, “and, with its few lighted windows, it no longer looks like a prison but like a place of refuge.” Despite the pretense of an adult drama of intrigue and infidelity, what lingers is a child’s frightened view of the strange goings-on.