From the Chicago Reader (June 14, 1991). — J.R.

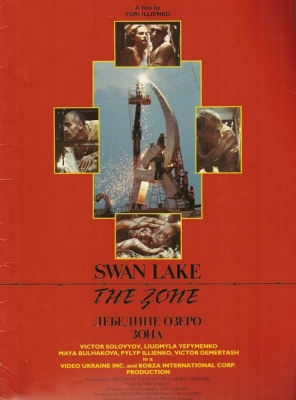

SWAN LAKE — THE ZONE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Yuri Illienko

Written by Sergei Paradjanov and Illienko

With Victor Solovyov, Liudmyla Yefymenko, Maya Bulhakova, Pylyp Illienko, and Victor Demertash.

One of the most fascinating things about Russian cinema is that we still know next to nothing about it. There are the socialist realist holdovers (Little Vera, for example, and Freeze — Die — Come to Life) and wannabe American releases (Taxi Blues), but the rest of the recent Soviet pictures that have made it to Chicago are interesting mostly because of what remains obscure and intractable about them — their refreshingly and, at times, bewilderingly different views of life and art.

The films that constitute the most obvious reference points in Soviet film history — a few key classics by Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dovzhenko, Kuleshov, Vertov, and closer to the present, the films of Paradjanov and Tarkovsky — have practically nothing to do with what ordinary Soviet moviegoers see most of the time. Even worse, we can’t take it for granted that these avant-garde works necessarily represent the best that innovative Soviet cinema has to offer, or that what we see of the Soviet mainstream is necessarily the best either.

If I hadn’t lived in Europe for several years, I would never have seen about a third of the best Soviet films I know: the first sound films of Kuleshov (The Great Consoler, about the life and stories of O. Henry), Pudovkin (Deserter), and Dovzhenko (Ivan) and Julia Solntseva’s rather insane 70-millimeter Stalinist spectaculars, especially The Enchanted Desna. None of them has ever been subtitled in English, and few are currently very well known in the Soviet Union either. [2020: today, at least the first two of these films are commercially available on DVD with English subtitles, and Desna can be accessed with subtitles at https://vimeo.com/22478 1509, password: SOLNTSEVAMOMI2017.)

The continued unavailability of these films and many others [in 1991] guarantees a skewed view of Soviet cinema. What I regard as the best post-Tarkovsky Russian film, Kira Muratova’s The Aesthenic Syndrome — probably the most thoroughgoing and shocking indictment of the contemporary world in movies, leagues ahead of any American movie in rage as well as stylistic range — as far as I know has yet to have a U.S. screening, much less a U.S. distributor. Maybe by the time we’re ready for it, we’ll be ready for Kuleshov’s 1933 masterpiece about O. Henry as well.

Early last month I attended two lectures at the University of Chicago by Yuri Tsivian, a Soviet film historian from Latvia, about prerevolutionary Russian cinema — one about censorship codes in that period, illustrated by several video clips, and a more general lecture followed by three films made in 1913 and 1914. (A touring show devoted to Russian cinema before the revolution is in the works and will eventually play at the Film Center.) What’s most amazing about these movies — dismissed by many modern Soviet filmmakers as bourgeois, decadent, and even “necrophiliac” — is their radical differences from such contemporaneous American movies as The Birth of a Nation: above all, their pronounced feminism and their visual sophistication, especially the varied camera angles, deep focus, and camera movements.

The most fascinating film I saw, Merchant Bashkirov’s Daughter (1913), belonged to a genre that, as far as I know, existed only in prerevolutionary Russia. “Blackmail films” were docudramas based on contemporary scandals involving wealthy merchant families, who were expected to pay off the filmmakers. But once that happened, the films were usually shown anyway, under new titles and with different names for the characters.

The value of these early films — including Merchant Bashkirov’s Daughter and the 1914 The Woman of Tomorrow, about a woman gynecologist at a time when there were already hundreds of them in Russia — is how much they have to tell us about an unfamiliar world and culture. The masterpieces cited above (from the 30s, 50s, 60s, and in the case of Muratova’s film, 1989) tell us things not only about history but about the present, and not only about Soviets but about ourselves.

Especially exciting in the post-50s work is a combination of realistic and nonrealistic modes, which might be called allegorical realism. This form of cinema seems to take place inside the mind rather than in the world, yet it’s full of realistic details in the settings as well as in its tactile sensations. Paradoxically, these conceptually abstract films are unusually concrete, immediate and richly textured physically, handling such elements as moving water with a sensuality missing from American and European movies.

Yuri Illienko’s Swan Lake — The Zone is no masterpiece, but it’s a lot more interesting than most American or European movies I’ve seen this year, and it has an enormous amount to teach us. Historically, it qualifies as the first truly independent Ukrainian feature: it was financed as an international coproduction with Sweden and Canada and coproduced by Illienko and Las Vegas symphony conductor (and fellow Ukrainian) Virko Baley. Its source is a series of stories composed (not written) by the great Armenian/Georgian filmmaker Sergei Paradjanov during his many years in prison. As Illienko explained to me at the Vancouver film festival last fall (mainly through a Ukrainian interpreter), Paradjanov was often denied writing materials in prison, so he learned to memorize the stories he made up. Illienko got him to recite them into a tape recorder, and wrote the script based on those recordings. Paradjanov was dying of cancer while the film was being made, but Illienko was able to show him the finished work before he died; the director even included one detail — a French magazine with a photo of Paradjanov and the caption “Maestro” — mainly for the pleasure he knew it would give Paradjanov.

What emerges from this unusual collaboration is not an “homage” to Paradjanov, at least not in the usual sense of that word. The visual and aural styles of the film have no apparent relationship to Paradjanov’s filmmaking, and the content is equally remote from Paradjanov films (at least those known in the West, all of which are set before the 20th century).

Illienko was the inspired cinematographer on Paradjanov’s Ukrainian Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (1964), and considering all the striking stylistic differences between this lyrical feature and Paradjanov’s subsequent work, there is good reason to suspect that Illienko effectively codirected the film as well. (Among Illienko’s previous films as a director are the long-banned A Spring for the Thirsty and The Eve of Ivan Kupalo, both made in the 60s.) Illienko later testified on Paradjanov’s behalf when he was arrested on multiple and mainly trumped-up charges, including “homosexual coercion,” in 1973 (after serving a long prison term, Paradjanov was arrested again in 1982). But it cannot be said that Illienko’s relations with Paradjanov were always friendly; back in the 60s, Illienko told me, Paradjanov even challenged him to a duel. Because Paradjanov was so obstreperous and antiinstitutional by nature, it was only a matter of time before the authorities caught up with him; he clearly needed friends wherever he could find them. Illienko remained an ally to the end.

What has all of this to do with Swan Lake — The Zone? For one thing, the prison where the film was shot is the same prison in which Paradjanov was incarcerated; most of the prisoners we see are real-life prisoners there today, so the film offers a horrifyingly lucid portrait of what Paradjanov’s life there must have been like, and what it continues to be like for more recent arrivals. (The very fact that this can be done in a contemporary Soviet film is noteworthy in itself; it’s difficult to imagine many — or any — American films about prison life adopting the same degree of candor.)

In most other respects, Swan Lake is a far cry from a documentary. Working almost completely without dialogue (so that subtitles are sparse) and with nameless characters, the film is usually easy enough to follow, though curiously some of the details mentioned in the press synopsis are not evident on-screen. To clarify this difference, I’ve included some of the information from the “official” synopsis in brackets.

At the beginning, the hero (Victor Solovyov) breaks out of the prison [three days before his sentence is over] and hides out in a huge, metallic hammer-and-sickle monument that stands at the prison gates. (Illienko told me that prison monuments of just this type are quite common in Russia, so the allegorical implications stem directly from social reality. Given all the symbolic and tactile ramifications of this claustrophobic location in the film, it functions not as a dry or pretentious symbol but as a “lived-in” allegory as well as a lived-in site.) On sorties from his hiding place, the man steals clothes from the trunk of a car and later tries to hitch a ride, only to be beaten by a carload of thugs; in his hideaway, drinking from bottles of champagne, he gets drenched in a rainstorm.

A woman (Liudmyla Yefymenko, Illienko’s wife) who lives nearby discovers his hideout, nurses him back to health, and becomes his lover. We also see her purchasing a train ticket, perhaps with the idea of escaping with him. Her son (Pylyp Illienko, the director’s son), who generally uses the monument as his own hideaway (where he leafs through the aforementioned French film magazine), expresses his disapproval of the couple by firing rocks against the monument with a slingshot when they’re inside [and by reporting the man’s whereabouts to the authorities].

Back in prison, the man attempts suicide and is pronounced dead and carried off to a morgue in a horse-drawn carriage. When he’s found to be still alive, the driver revives him by giving him blood for a transfusion, administered by an old woman. The man returns to the prison voluntarily, but is treated roughly by both the authorities and the other prisoners, who tell him he must spit in the face of the guard who saved him and then abide by the punishment for this action: another five years in prison. He slits his wrists, and the next morning his dead body is stared at by the other prisoners and ignored — or not noticed — by the guards.

The film’s title refers to the swans in the wasteland surrounding the prison. In an early sequence they’re briefly and improbably glimpsed inside the prison, when we see the clamoring prisoners getting hosed down by the guards. There’s also a very strange animated sequence, which may be taking place inside the hero’s head when he’s hiding inside the monument, that shows blue swans against a blue background flapping their wings.

I suppose these swans are allegorical to the same degree the monument is — or the map of the world on which the hero is laid in the morgue, the map covering a board placed over a bathtub containing another corpse. But the poetic meanings of the swans, as of the other details, are clearly meant to be experienced rather than rationally decoded. The worst, most demeaning approach to a movie like Swan Lake — The Zone would be to reduce it to a “purely” political allegory. True, Soviet directors tend to be more directly political than their American and European counterparts — Illienko expressed only contempt for Julia Solntseva’s films because of their Stalinist underpinnings, and Paradjanov, despite his own martyrdom, criticized Tarkovsky after glasnost for making his last films abroad. It’s also true that Soviet directors don’t usually display our bad habit of considering their ideology and their aesthetics as separate and unconnected entities. More holistic about the spiritual breath of reality, these filmmakers bring a vitality to allegory by treating it as an adjunct to lived experience rather than as an alternative to it.

An important part of the “realism” that plays against the “abstraction” of Swan Lake — The Zone is the film’s highly inventive sound track. This kind of realism, however, usually gives a particular inflection to the images rather than reproducing or reinforcing them in the conventional manner. When the film opens with the hero fleeing in long shot through a wasteland, what we hear is the sound of his labored breathing. Similar aural close-ups are later accorded to the clinking of bottles inside the monument, the tinkle of the woman’s hammer-and-sickle earrings, and many other small, odd sounds. The effect is always to intensify the physicality of the object that is aurally highlighted. (Tarkovsky and other Soviet contemporaries have used sound similarly, but the only American or European parallel that comes immediately to mind is Jacques Tati, who also avoids expository dialogue. Is it only coincidence that Tati’s family background was Russian, his original name Tatischeff?)

Conventional verisimilitude is not to be expected in a film of this kind. The hero’s proximity (and later the heroine’s) while inside the monument to prison guards and activities, which the sound track emphasizes, makes it implausible that he could remain undiscovered. It’s almost equally implausible that at the end the guards, playing what looks like dominoes, would fail to notice his “crucified” body a few yards away. Both cases recall Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Purloined Letter,” where the centrality of the hidden object is an essential part of its invisibility; it’s worth stressing that throughout most of the film the hero exists as an object rather than a character.

It could be argued that allegory and symbolism in contemporary Soviet films are legacies of the repressive past, when meanings often had to be cloaked in ambiguity in order to get by the censors. If there’s any truth to that hypothesis, I don’t think it means Soviet cinema today is any less “free” than our own; if anything, it may suggest the contrary because of the expressive registers developed as a consequence of repression.

Much as the elaborate constraints of Hollywood under the studio system gave a stylistic coherence to many movies that’s hard to find today, comparable constraints may have provided the impetus for the “allegorical realism” of contemporary Soviet cinema. We’re often quick to condemn the former restrictions of Soviet cinema and exalt the former constraints of Hollywood, but the fact remains that Orson Welles had as hard a time as Sergei Eisenstein did. And now that a good many Soviet filmmakers seem to be freer than most of their American and European counterparts, it’s about time the rest of world cinema heeded the many formal, stylistic, and expressive alternatives they have to offer.