From the Chicago Reader, April 9, 1993. — J.R

FILMS BY MICHELANGELO ANTONIONI

Jean-Luc Godard: The drama is no longer psychological, but plastic . . .

Michelangelo Antonioni: It’s the same thing.

— from a 1964 interview

Just for my own edification, I’ve put together a list of the 12 greatest living narrative filmmakers — not so much personal favorites as individuals who, in my estimation, have done the most to change the way we perceive the world and are likeliest to be remembered and valued half a century from now. The names I’ve come up with are Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson, Federico Fellini, Samuel Fuller, Jean-Luc Godard, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Stanley Kubrick, Akira Kurosawa, Nagisa Oshima, Alain Resnais, and Ousmane Sembene.

Only five have had their most recent feature distributed in the U.S. — Bergman, Bresson, Kubrick, Kurosawa, and Sembene. Fellini may have recently earned a special Oscar, but that doesn’t mean we can expect to see his latest film anytime soon, and though Godard’s next-to-last feature, Nouvelle vague, has finally come out on video, that doesn’t mean we can expect to see it properly, on a big screen.

We can, however, see nearly all of Antonioni’s work — 14 of his 15 feature films and most of the dozen or so shorts — in brand-new prints at the Film Center this month and next. (The missing feature is The Passenger, of 1975, which Jack Nicholson, the film’s star, owns the American rights to and is withholding from this retrospective for mysterious reasons of his own. It’s available on video only with the image cropped and in incomplete form.)

All things considered, this is the most important retrospective to have come to Chicago during the five and a half years I’ve lived here, and for those unfamiliar with most of Antonioni’s work — probably most people — it provides the opportunity for some major, mind-bending discoveries. While it’s regrettable that the films are being shown out of strict chronological sequence because of print availability — L’avventura won’t turn up until next month, many weeks after its immediate successors, La notte and Eclipse, have shown — this is not as serious an impediment to the understanding of the work as it would be with a filmmaker like Godard.

Whatever one thinks of Fellini, it seems to me inarguable that Antonioni is far and away the greatest living Italian filmmaker; indeed, with the exception of Roberto Rossellini, he is probably the greatest of all Italian filmmakers. Although he is hardly known at all to younger viewers, that’s not because his films — made between the late 40s and the early 80s — have dated in any significant way; it points, rather, to the fact that the critical community and most of the rest of world cinema have regressed to the point where they can no longer even remember why such a fuss was made over Antonioni in the 60s — or even that there was a fuss. Because of the basic challenges his work has posed from the beginning — challenges to our notions about story telling, realism (including Italian neorealism), drama, society, the modern world, and reality itself — he has been more consistently misunderstood and attacked than any other modern filmmaker of comparable importance. (The only time audiences truly kept abreast of him was during his period of popularity in the 60s.)

Moreover, the supplementary tools at our disposal for clearing the air are far from ideal. There are only two book-length critical studies of Antonioni in English in circulation; one of these is pretty awful and the other is first-rate, but it’s the pretty awful one — Seymour Chatman’s Antonioni, or the Surface of the World (1985) — that is most readily available. (The other one is Sam Rohdie’s Antonioni, published in 1990 by the British Film Institute, and it’s well worth hunting down.)

The period when Antonioni was fashionable — though he certainly remained controversial even then — stretches from the 1960 premiere of L’avventura at Cannes to the catastrophic release of Zabriskie Point in 1969. Undoubtedly his commercial success peaked with Blowup in 1966, but perhaps the most significant indication of his reputation during this period was Sight and Sound‘s top-ten survey — a poll of international critics conducted every ten years since 1952. The winter 1961-’62 survey placed L’avventura in the number-two slot, right below Citizen Kane. L’avventura slipped down to fifth place in 1972, then seventh place in 1982, and finally went off the list entirely last year. (Perhaps significantly, the only other time the critics had given a recent film comparable standing in this poll was 1952, when The Bicycle Thief, made in 1949, scored first place; curiously, Citizen Kane, first in all four polls since 1962, didn’t place at all in 1952.)

The degree to which Antonioni remained in intellectual vogue in the U.S. during this period fluctuated wildly. The original defenders of L’avventura were mainly literary types like Dwight Macdonald and John Simon, both of whom turned against Eclipse only a year or so later, as did a rising star named Pauline Kael (who had also championed L’avventura). Andrew Sarris, who later came back in force to defend Blowup, was already cracking jokes about “Antoniennui” in the early 60s. Many American critics tended to be scornful of Antonioni’s continuing use of Monica Vitti (in four features in a row) because of her limited technical range as an actress, much as Godard was criticized concurrently for repeatedly using Anna Karina. And the fact that Antonioni’s concentration on the idle rich in L’avventura and La notte coincided with the milieus of such contemporaneous movies as La dolce vita and Last Year at Marienbad was enough to make Kael ignore the radical formal differences between Fellini, Resnais, and Antonioni and link them all together in an otherwise amusing broadside called “The Come-Dressed-as-the-Sick-Soul-of-Europe Parties.”

The problem was, many of these people were already starting to adopt a critical attitude that assumed it was possible to know immediately and without a doubt what was good and bad in a movie the precise moment it appeared — an attitude that Kael’s disciples have subsequently adopted with even more shrillness and impatience. Intricate, melancholic mood pieces like Antonioni’s, which invite and reward — and occasionally even require — weeks of mulling over, could find no place at all within this approach, so fewer and fewer critics wound up dealing with them, seriously or otherwise. Better to come up with a clever quip about them right away than continue to think about them for a week or two, or even revise an opinion about them when the review got reprinted (which Kael has never done about a single movie in any of her 11 books — confidence with a vengeance, and one that necessarily rules out a whole cinema of uncertainty). In a marketplace virtually predicated on planned obsolescence, movies that stick in one’s craw rather than speed through the digestive system are bound to cause trouble.

Born to a middle-class family in 1913 in Ferrara, a small provincial capital in northeast Italy near the Po River, Antonioni didn’t shoot his first feature until his mid-30s. He studied business and economics at the University of Bologna, worked in a bank, flirted with playing professional tennis, and became interested in cinema during the last decade of Italian fascism. Starting out as a film critic and short-story writer for his hometown newspaper, and displaying a taste for atmosphere rather than plot or character, he made a few abortive stabs at filmmaking before moving in 1940 to Rome, where he contributed articles to several film journals.

While the prevailing aesthetics of his colleagues at the time were realist, populist, and socially committed, Antonioni was more interested in formal experimentation. As Rohdie and other critics have pointed out, it wasn’t that he didn’t share the preoccupations that would eventually blossom into Italian neorealism; it’s just that he came at them from a different angle.

This difference can already be felt in his early short documentaries, mostly made during the late 40s, but it becomes decisive in his first feature, Cronaca di un amore (Story of a Love Affair, 1950), which broke with the popular perception of neorealism not only in its attention to form but in its choice of an upper-class milieu — a milieu that he stuck to for most of the remainder of his career. Only Il grido (The Cry), made in 1957, is situated squarely in a working-class environment, and Antonioni himself has said, “I prefer to set my heroes in a rich environment because then their feelings are not (as in the poorer classes) determined by material and practical contingencies.”

One good example of Antonioni’s distinctive version of neorealism is his sketch Tentato suicidio (Suicide Attempt), his remarkable contribution to the 1953 neorealist feature Amore in citta (Love in the City), made the same year he turned 40 and after he already had three features under his belt. A number of men and women who have attempted to commit suicide (as we learn from the male offscreen narrator) are seen filing into the bare white confines of a film studio and are framed in various clusters. Then the stories of a few women among them are recounted, both by the narrator and by the women themselves, most often in the original settings where these attempts took place, with the narrator often asking questions and the women, in the process of answering, restaging certain portions of what originally happened.

In the second story, the camera itself partially “restages” a woman’s trying to drown herself in the Tiber by moving toward the center of the river and then lingering on the choppy surface of the water around the base of a bridge while she narrates offscreen — not exactly point-of-view shots, yet images that clearly imply someone’s subjectivity. In the final story, a young aspiring actress lying on her bed describes slitting her wrist and rather unconvincingly re-creates the gesture with a razor before suddenly showing the camera the actual scar on her wrist; then she continues to describe what happened, in the past tense.

For critics like Chatman, who echoes the objections of many of Antonioni’s contemporaries, such procedures qualify only as failed neorealism: the aspiring actress, for instance, is “suspiciously photogenic” and “one could perversely imagine her attempting suicide just to get into Antonioni’s movie. . . . No real effort is made to find out what lies under the surface.” But it might be argued that for Antonioni, the mysteries he is investigating exist precisely in surfaces — the recitations and actions of these women, the settings, even the ugly scar revealed on a woman’s wrist. We quickly perceive that the original suicide attempts themselves may have been partially feigned — staged gestures designed to produce certain effects — and that their restaging can only compound our uncertainties rather than dissipate them. The fact that the narrator remains unseen further foments our doubts and suspicions without confirming any of them. Chatman’s self-admittedly perverse imagination is not shared by Antonioni. The filmmaker is not interested in “penetrating” artificiality to “get at” the truth — as Chatman, with his comic-book version of the neorealist aesthetic, would have him do. In the context of this sketch, it would constitute a violation of the women involved.

Antonioni is interested, rather, in the truth of not knowing, the truth of surfaces, the truth of reality and falsity alike. Agnostic toward what is commonly labeled “real,” he is ultimately more interested in posing the right questions than in coming up with easy answers, and in this respect he becomes the blood brother of a true neorealist like Rossellini. The Italian title of The Passenger, one should note, is Professione: reporter. If we consider Antonioni an investigative journalist in all of his features, he is one with a painter’s eye, a choreographer’s sense of movement and rhythm, and a metaphysical imagination — a journalist whose questions never stop.

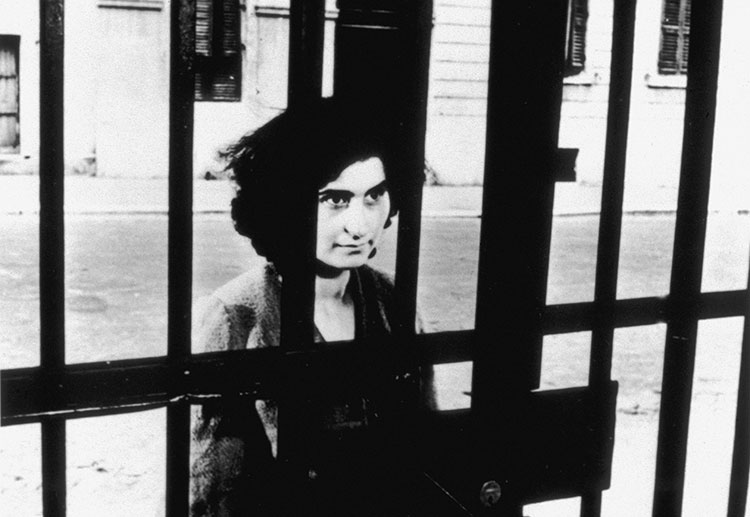

Indeed, many of Antonioni’s features — Cronaca di un amore, Le amiche (The Girlfriends), L’avventura, Blowup, The Passenger, Identification of a Woman — resemble detective stories for long stretches. But especially in the case of the last four, their mysteries are not solved but eventually displaced by other mysteries. The pivotal narrative event in L’avventura is the sudden disappearance of Anna (Lea Massari) from a volcanic Sicilian island during a pleasure cruise she is taking with her lover Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti), her best friend Claudia (Monica Vitti), and a few others. Her affair with Sandro, a once-idealistic architect who has become more concerned with money than creativity, has not been going well, and her earlier behavior leads us to suspect that she has either committed suicide or escaped from the island on a passing fishing boat as a malicious prank. (Interestingly, until Anna disappears, the island itself is simply a picturesque setting for a yachting party. But once Sandro and Claudia begin to search for Anna, covering and re-covering the same areas, it comes alive with clues and potential meanings, as if a character in its own right.)

Following a trail of leads back on the mainland, Sandro and Claudia travel together from town to town in search of Anna, and embark on an affair of their own in the course of their investigation. Much of what they encounter on their journey expands the thematic scope of the film — with reference to eroticism, love, and lost ideals — but none of it solves the mystery of Anna’s disappearance. Our growing suspicion that the movie isn’t “going anywhere,” that it’s constantly in danger of collapsing into random incidents, corresponds precisely to the characters’ doubts — emotional, ethical, and existential — about their own experiences. The slow pacing central to Antonioni’s masterful establishment of mood and atmosphere grants us ample space in which to wander and worry, just like Claudia and Sandro. At the same time, the sheer and constant beauty of Antonioni’s framing, his choreography of camera and actors, his musical sense of duration and editing, and his sculptural sense of space all leave powerful and lingering aftereffects. In contrast, aesthetically empty movies usually satisfy our narrative needs and leave us with nothing after they’re over — except room for more of the same.

Still, given this unsettling displacement of our narrative expectations, which occurs in different forms in the other films, it’s not difficult to understand why Antonioni’s films can provoke anger. It’s rather as if Citizen Kane concluded without telling us what Rosebud meant — and significantly, perhaps no other filmmaker ever expressed more irritation with Antonioni’s methods than Orson Welles, whose similarities with Antonioni in terms of deep-focus and mobile mise en scène and black-and-white chiaroscuro are offset by radical differences in his approaches to actors and various theatrical elements. (For all his profound links with architecture, sculpture, painting, music, dance, and the novel, Antonioni has virtually no relation at all to theater, and he isn’t even remotely a director of actors in the sense that Welles was. For him, actors are Jamesian “figures in the carpet,” not fellow weavers.)

But Antonioni’s thwarting of narrative conventions fails to account for the fury of the American responses to Zabriskie Point, the Chinese responses to his documentary China (which inspired Umberto Eco’s essay “The Difficulty of Being Marco Polo”), or Vincent Canby’s review of Identification of a Woman in the New York Times, which virtually terminated Antonioni’s career a little over a decade ago. (A subsequent stroke has rendered Antonioni paralyzed, so the odds of his working again are practically nil, though I’m told that he remains alert: he was present at symposia on his work accompanying this touring retrospective held in New York and Los Angeles.) The reasons his work as a whole poses profound threats to any number of ideologies is too vast a subject to be broached here, but brief considerations of the first and last of these “disasters” may offer a few helpful clues.

Zabriskie Point, Antonioni’s only American feature, came on the heels of his biggest success, Blowup, a movie that put sexy, “swinging London” on the map even more decisively than either Darling or A Hard Day’s Night did. Evidently expecting Antonioni to similarly glamorize radical youth in the U.S., MGM was disappointed with the spectacular and fanciful poetic fable that resulted, as was almost everyone else. Intellectuals and ordinary spectators, radicals and conservatives, and everyone else in between — including the romantic leads — denounced the movie in no uncertain terms. But today it’s clear that the film has aged a lot better than its detractors. Perhaps because Antonioni regarded “America” as a natural site for iconographic fantasies, he worked more expressionistically and less realistically than he had in any of his Italian movies, even including the color experiments in Red Desert, and he did at least as much with billboards as any of the best pop art. And in the final, apocalyptic sequence — a dream of destruction in which a striking desert ranch house repeatedly explodes, raining down a profusion of consumer products that add up to an astonishing catalog of the modern world — Antonioni created what is surely one of the most powerful and beautiful images of his career. (It’s the precise antithesis of the lovely fantasy sequence near the end of Red Desert–a peaceful, utopian story recounted by the neurotic heroine to her little boy about a girl and the sea.)

For all its beauty, Identification of a Woman (1982) is probably not one of Antonioni’s best films, though it’s still one of the great Italian films of the past decade. It represents such a departure in terms of its studio filmmaking style and its theme (the personal life of a filmmaker) that when I saw it at the New York film festival over ten years ago I found it difficult to come to terms with (even while I found myself passionately defending it for its highly erotic handling of female sexuality and its distinctive view of life in contemporary Italy). It’s certainly every bit as mysterious and enigmatic as his previous work, but by 1982 the lack of instant certainty that is the staple of today’s reviewing, especially on TV, was becoming harder and harder to defend.

Prior to its festival premiere, the film had found a small U.S. distributor and tickets to its screenings were sold out. Then came Canby’s review, which suggested that “Mr. Antonioni” make a careful study of the films of Woody Allen so that he could learn to be less pretentious, and immediately afterward hundreds of tickets were returned to the festival box office and the distributor promptly dropped the film. The movie was never released in the U.S., and thanks in part to this loss of potential revenue, Antonioni was never able to finance another feature, though he had many projects. The biggest irony of all came when Woody Allen — who’d paid extended homage to Antonioni in an episode of Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex . . . but Were Afraid to Ask ten years earlier — hired Carlo Di Palma, who shot Identification of a Woman (as well as previous Antonioni pictures in color), for many of his own pictures.

I don’t mean to imply that Canby’s imbecilic review — written four years after unpretentious Woody’s Interiors — was responsible for ending Antonioni’s career. I’d place most of that blame on the shoulders of Canby’s hip New York audience (including distributors), who were so fearful of having to make up their own minds that they forfeited that privilege for audiences everywhere else. (With our tacit consent and approval, they’re still doing it to other pictures, too.)

In all fairness, one can’t accuse Antonioni’s pictures of fostering uncertainty about everything. The stories and even the characters and their identities may eventually start to dissolve, forcing us to reconsider various elements in the pictures that we have taken for granted, but the sheer persistence of certain locations is so strong that it calls to mind a famous remark by the French Catholic writer Charles Péguy: “Nothing will have taken place but the place.” These locations haunt our memories like sites with highly personal associations from our own pasts. A few examples among many would include the English parks where corpses are discovered in both I vinti (1952) and Blowup, an abandoned set of newly constructed buildings in the middle of nowhere in L’avventura that suggest Giorgio De Chirico’s surrealist paintings, and a marshy industrial wasteland bordering a factory — presented as surprisingly beautiful in certain shots — in Red Desert (1964).

The aforementioned apocalypse at the end of Zabriskie Point is only one of three extraordinary codas in Antonioni’s work, each involving a startling rupture in style and narrative, while at the same time centering on the spell cast by a specific location as dusk approaches. At the end of The Passenger — a film that, like Blowup, is much better in handling physical environments than in grappling with literary conceits — the hero’s mysterious death on a motel bed in rural Spain occurs offscreen; the camera has momentarily turned away from him and drifted out the window to contemplate the seemingly everyday comings and goings of people in a village square. As in the sequence at the end of Zabriskie Point — and in the majority of other great moments in Antonioni’s cinema, for that matter — the absence of dialogue helps a lot. Antonioni’s selective use of sound and choreographed images tend to be a lot more potent and intuitive than his words. Unfortunately, it’s only the latter that can get quoted in reviews; the charges of pretentiousness lodged against Antonioni nearly always derive from this disproportionate emphasis.

In the final scene of Eclipse (1962) — my favorite Antonioni feature, and the one that concludes the loose trilogy started by L’avventura and La notte — a lingering over an urban street corner while night begins to fall, effected through montage rather than an extended take, becomes one of the most terrifying poems in modern cinema simply through its complex poetry of absence. The lead couple in this film, played by Alain Delon and Monica Vitti, have previously planned to meet at this corner, in front of a building site. (Another building site figures in the opening sequence of L’avventura.) The unexplained fact that neither character shows up is perturbing, but because their affair has been more frivolous than serious, it hardly accounts for the overall feeling of desolation and even terror in this sequence.

It’s almost as if Antonioni has extracted the essence of the everyday street life that serves as background throughout the picture, and once we’re presented with this essence in its undiluted form, it suddenly threatens and oppresses us. The implication here (and in every Antonioni narrative) is that behind every story there’s a place and an absence, a mystery and a profound uncertainty, waiting like a vampire at every moment to emerge and take over, to stop the story dead in its tracks. And if we combine this place and absence, this mystery and uncertainty into a single, irreducible entity, what we have is the modern world itself — the place where all of us live, and which most stories are designed to protect us from.