This appeared in the March 3, 1995 issue of the Chicago Reader, under a slightly different title (“TV and Not TV”). — J.R.

Angèle

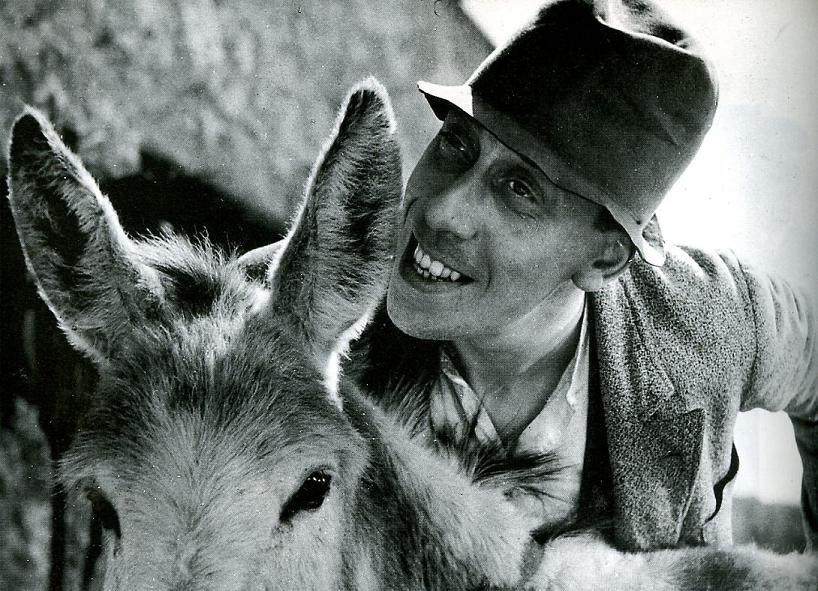

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Marcel

Pagnol

With Orane Demazis, Fernandel,

Henri Poupon, Jean Servais,

Toinon, Delmont, and Andrex.

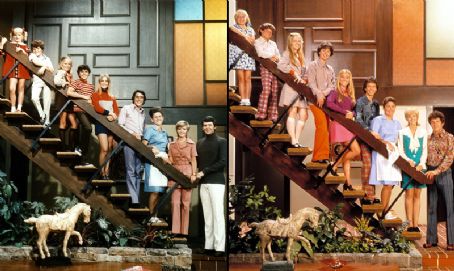

The Brady Bunch Movie

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Betty Thomas

Written by Laurice Elehwany, Rick

Copp, Bonnie Turner, and Terry

Turner

With Shelley Long, Gary Cole,

Michael McKean, Christine Taylor,

Jennifer Elise Cox, and Henriette

Mantel.

When it comes to Marcel Pagnol (1895-1974) and The Brady Bunch (1969-1974), I’m strictly a novice. The Brady Bunch ran on prime time on ABC when I was living in Paris, but even if I’d been in the United States I would have found other things to do with my Friday nights; the show obviously made its deepest imprint on the preteens who had to stay home. I never saw any Pagnol movies during that period either: my French wasn’t fluent enough for me to follow the Provençal patois of the dialogue without subtitles, and anyway, the standard line on Pagnol’s movies back then was that they were “canned theater.” (Pagnol himself was the main culprit in fostering this impression: “Film is the art of imprinting, fixing, and diffusing theater,” he wrote in 1933.)

After I returned to the States I made a stab at catching up with Pagnol via two or three scratchy 16- millimeter prints — César and The Baker’s Wife are the only two I can recall — which left little impression. I made no attempt at all to acquaint myself with The Brady Bunch, despite many TV reruns, until I caught a couple of episodes on TBS shortly after seeing The Brady Bunch Movie.

But even though I’m not an expert on Pagnol or Angèle (1934) — commonly regarded as his greatest film, playing this Saturday in a beautiful new 35-millimeter print during Facets Multimedia’s long-overdue Pagnol retrospective — or on The Brady Bunch Movie, still playing commercially all over town, these very different films offer fruitful comparisons. Released 61 years apart, they are both highly popular populist entertainments about the way a particular group of people in a particular closed environment live and behave, and together they provide a good many clues about how popular entertainment has changed during those six decades. Furthermore, it’s curious that The Brady Bunch Movie — a product of my own culture and time and in my native language — strikes me as an esoteric object, an artifact from another planet, while Angèle — made in an unfamiliar language about an unfamiliar period and culture — communicates to me fully and directly. Obviously this won’t be everyone’s experience, but I can’t believe that my feeling is unique either. To organize my thoughts about movies that are at once so similar and so different, I’ve grouped my impressions in three categories.

Nationality/regionalism. In most people’s minds, Angèle will be as quintessentially French as The Brady Bunch Movie is quintessentially American, but in each this essence is framed and communicated very differently. In the 50s the late Andre Bazin noted that “together with La Fontaine, Cocteau, and Jean-Paul Sartre, Pagnol completes the average American’s ideal French Academy,” and even recently four French movies based on Pagnol material (Jean de Florette, Manon of the Springs, My Father’s Glory, and My Mother’s Castle) have been enormously successful. But as Bazin went on to say, “Pagnol paradoxically owes his international reputation above all to the regionalism of his work.” The local feeling of Pagnol films — chiefly set in Provence and steeped in the precise details of life in southern France — is what makes them seem so French.

Angèle is one of Pagnol’s rare adaptations of others’ work, loosely based on Un de Baumugnes, a novel by Provençal writer Jean Giono. The story is fairly elementary: a farmer’s daughter named Angèle (Orane Demazis) gets lured away to Marseilles by a fast-talking pimp (Andrex). Some time later a loyal farmhand, Saturnin (Fernandel), goes looking for her and finds her working as a prostitute, with an illegitimate child; all she knows about the long-gone father is that he was a sailor “from the north” who didn’t speak French. Saturnin brings her back to the farm, where her disgraced father (Henri Poupon) hides her and her infant in the barn, saying, “I’m offering you not a home, but a hideout.” Eventually she’s saved by Albin (Jean Servais), a principled mountain peasant who knows about her past but is willing to overlook it, and the remaining drama consists of his efforts to convince her father to let him marry her. The “Frenchness” of the story resides largely in the fully realized details of everyday life in rural Provence: the men’s baggy trousers and striped shirts, the women’s isolation and lack of freedom, the rocky hills, the fixed moral codes, the casual social interactions, the behavioral quirks (such as Saturnin polishing his spoon on his jacket sleeve with a horsey grin as he sits down to a farmhouse meal), the distinctive speech patterns, and so on.

Pagnol was first a very successful playwright in Paris’s boulevard theaters, then formed an independent film production company in his native Provence after the beginning of talkies. What made Angèle, his fourth solo feature, especially innovative was that it was shot exclusively in natural locations, in direct sound, without any recourse to studio facilities (though Pagnol had established a studio of his own by that time in Marseilles); he even shot the Marseilles brothel scenes in the same remote Provençal farmhouse that provided most of the other interiors. And the bustling street scenes in 30s Marseilles followed by Pagnol’s gracefully moving camera have a very exciting vitality and presence, worlds apart from “canned theater.” Angèle has been called the first neorealist film, despite the fact that it uses only professional stage and vaudeville actors, because the natural surroundings are so vivid and play such an integral role in the film. Much of the film’s Frenchness, in other words, is France itself.

The Brady Bunch Movie has its own regional qualities, though whether the “region” is southern California or American television is worth pondering. At the beginning the movie takes great pains to establish the setting as contemporary Hollywood, but once we’re reintroduced to the Bradys and their peculiarly insulated 70s world, the sense of an actual physical location becomes increasingly attenuated. Since most of the comedy is based on the premise that the original Brady family have been preserved as if in formaldehyde while the fashions, folkways, and assumptions of the world around them have radically changed, the movie takes great care to reproduce the look and feel of the original show, minus the laugh tracks and all the original actors: interiors and exteriors alike are as overlit as Bavarian beer commercials, and even the show’s flip-flopping transitions between sequences are revived.

But because the world of 90s Hollywood is as stylized here as the Brady domicile, the movie gives very little sense of being set in a particular place and time, whether the 70s or the present — unless, that is, we accept the world of American TV over the past quarter of a century as a spatiotemporal place, as the movie does. (Indeed, as much of the planet does — the movie’s potential audience is both very broad and very narrow: it includes everyone who’s ever watched The Brady Bunch on TV but excludes everyone who hasn’t.) The Bradys’ AstroTurf lawn and Formica furnishings are no more artificial and crude than the supposed “real” world of 90s Hollywood: according to this movie, such things as lesbianism and high crime rates are the main facts of 90s life; of course lesbians and crime were around in the 70s but didn’t appear much in 70s sitcoms, so their “reality” hasn’t been verified until recently. Apart from a few cellular phones and a metal detector in a high school, most of what this feature reveals about the 90s is every bit as circumscribed as what the TV show revealed about the 70s. (In this respect the movie is a far cry from the Rip Van Winkle-ish satire of Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye, which planted a noble 40s Philip Marlowe in a cynical 70s Hollywood — though even Altman and his writers didn’t sustain the conceit.)

Bear in mind that the original squeaky-clean Bradys flourished during the height of the Vietnam war and the most strident final phases of the counterculture, which suggests that the denial of contemporary reality in this movie parallels the show’s denial during the 70s. But the film’s peculiar mixture of contempt and affection for the Bradys doesn’t offer a clear or fixed vantage point for a coherent satirical attack on the 70s or the 90s. (A rougher version of the same confused mixture can be found in the obscene, incestuous sitcom in Natural Born Killers, “I Love Mallory,” this time with a laugh track.) It’s clear that, regardless of how they value the movie, some audience members in their 30s or younger find a charge in it that’s unavailable to older viewers — a charge that’s undoubtedly related to their disillusionment about growing older. (“Put on your Sunday best, kids, we’re going to Sears,” seems one of the movie’s key lines in this respect.)

The fact that today the Bradys are hopelessly out of fashion seems the focus of the humor and anxiety, but this movie doesn’t come close to articulating the point that the Bradys were no less hopelessly in fashion in the 70s. In fact, even in the 70s the Bradys were both in and out of fashion, and judging by the show’s countless spin-offs — an early-70s Saturday-morning cartoon series (The Brady Kids), a 1977 variety show (The Brady Bunch Hour), a 1981 television sequel series (The Brady Brides), countless trivia books, and Chicago’s own The Real Live Brady Bunch, which has toured nationally and internationally — they have been triumphantly in and out of fashion ever since. Yet undoubtedly their appeal throughout the years has been as crazy mirrors for the audience, and the passage of time has only further displaced the show’s characters in favor of its true subject, its viewers.

To me, as one outside this loop, The Brady Bunch Movie resembles nothing so much as a hate letter to America — a more extreme version of the assault on middle-class glibness and inertia found in W.C. Fields comedies of the 40s, but with one curious difference: the rebellious and bilious Fields character is no longer on-screen but out somewhere in the audience, railing against the show and all it represents. Intertwined with this hatred is a nostalgic recognition that, despite its mendacity, The Brady Bunch is who we are and what we’ve been; like TV itself, it’s all we’ve got. That’s perhaps what’s most American of all about the movie, and it’ll be interesting to see whether this quality makes it suitable for export.

Characters. Both Angèle and The Brady Bunch Movie disperse their focus across all the central characters. There’s no hero in either movie, just lots of crisscrossing intrigues between various factions; what matters most in both is the preservation of the family and the community, not the triumph of any one individual.

Sherwood Schwartz — the producer of the original Brady Bunch and coproducer of the movie — has said that his inspiration for the TV show was, first, a newspaper report that 30 percent of all marriages included a child or children from a former marriage and, second, a story from his daughter about a friend in junior high who had to decide whether to give a ticket to the school play to his mother or his new stepfather. The eight Bradys are a mother and her three daughters from a previous marriage and a father and his three sons from a previous marriage — a combo that turns the household into two armed camps usually split by gender, though in many disputes Alice the maid serves as tiebreaker and moral arbiter. The only other significant characters in the movie were mentioned on the original show but never seen: next-door neighbors Mr. and Mrs. Ditmeyer (Michael McKean and Jean Smart). He’s an evil real estate salesman conniving to make the Bradys sell their house so a mini-mall can be built on their block, and she’s a lush who flirts with the Brady males.

The world of Angèle is more profoundly patriarchal. There are only two women of any significance, the eponymous heroine and her mother, and except for Angèle’s decisions to flee Marseilles, return to the farm, and accept Albin as a husband, all decisions are made by the menfolk: the pimp, Angèle’s father, Saturnin, Albin, and Amedee (a geezer who’s Albin’s friend, roommate, and accomplice). But the characters in Angèle are split more by social propriety than by gender — the question of what to do about Angèle, a once-dutiful farmer’s daughter who’s come home in disgrace. One can’t really speak of armed camps here despite the father’s recalcitrance, because in this rural universe everyone knows everyone else’s business and everyone talks to everyone else about it. What lingers most in the mind about these country folk is their sincerity, earnestness, and integrity and the patient way they iron out their differences, a kind of firmness that Pagnol unpatronizingly appreciates and understands without ever idealizing. There are no villains in this universe and, even more unexpected, very little sentimentality (a quality that is allegedly more prominent in some of Pagnol’s other movies).

Dimensions and durations. The Brady Bunch Movie resolves the whole mini-mall problem — fostered by the fact that all the Bradys’ neighbors have already sold their homes, while the Bradys have recently discovered that they owe $20,000 in back property taxes — virtually by fiat rather than through any ingenuity of plot construction. But the family conflict in Angèle is worked through carefully and honestly, point by point, without the constricting rhythms of sound bites and punch lines. Of course the TV format necessitates defining and resolving difficulties within the tight segments created by commercial breaks, a fact the movie chooses to flaunt as camp. The assumption is that TV is by definition fake and unimportant, though nothing else is sufficiently real or important to be offered in its place; maybe we don’t know who we are, but at least we know who the Bradys are, and since our very lives are intertwined with theirs, they automatically have a resonance of a very special kind.

Pagnol certainly knows who his characters are, and much of the relaxed density of Angèle derives from that intimate knowledge. (Probably the only other filmmaker who knows his characters, their settings, and their life-styles as thoroughly is Yasujiro Ozu.) Part of what Pagnol knows about them is that they’re long-winded; circumlocutions and digressions are the order of the day, a sort of lazy, southern speech that seems to echo the rises and declivities of the surrounding terrain. To go anywhere in this countryside, it seems, you have to walk or ride up and then down again, around and about — there are no straight lines here, and Pagnol’s dialogue and plot, unrestricted by the need for commercial breaks, are similarly meandering.

According to the film’s sound engineer, the original rough cut of Angèle lasted eight hours; the final version runs 132 minutes despite the slender plot. The original length of Pagnol’s 1952 version of Manon of the Springs (a film regrettably missing from the retrospective at Facets) was five or six hours; the distributors reduced it to slightly over three. As Bazin put it, “To ask Proust to write À la recherche du temps perdu in 200 pages would be senseless. For quite different but no less imperative reasons Pagnol could not tell the story of Manon des sources in less than four or five hours, not because essential things take place, but because it’s ridiculous to stop the storyteller before the thousand and first night.”

Which is another way of saying that Angèle rambles, but always with a purpose; every time the plot or characters dawdle, the real world leaks through in all its wonder. Pagnol’s people have lots of air around them, and the sun splashes their faces and the rocky countryside like a glittering paintbrush so that the light exuberantly overflows the borders of every frame. One emerges gratefully drenched in the warmth of these people, this time, and these places.