From the Chicago Reader (March 23, 2001). — J.R.

15 Minutes ***

Directed and written by John Herzfeld

With Robert De Niro, Edward Burns, Kelsey Grammer, Avery Brooks, Melina Kanakaredes, Karel Roden, and Oleg Taktarov.

A first-rate Hollywood entertainment, 15 Minutes is more than a little schizophrenic, a shotgun wedding between two seemingly irreconcilable genres — the buddy/cop action thriller and the angry social satire. It can’t even be unambiguous about the reason for its title. Presumably to placate the action-thriller buffs — some of whom are bound to be pissed off because satire is what closes in New Haven — there’s a throwaway line toward the end of the movie in which a vengeful cop is told he’ll have custody of the killer of his slain colleague for 15 minutes. Far more important is the satirical reference the movie bothers to cite only in the press notes: Andy Warhol’s 1968 assertion that “In the future everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.”

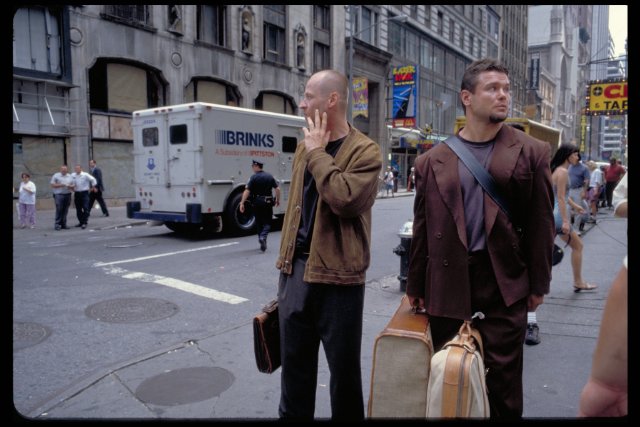

I’m a satire buff, but I have to confess that I do like at least a couple of the straight-ahead and relatively mindless action sequences: several cops chasing a Czech killer through busy midtown Manhattan traffic, while the killer, Emil, and his simpleminded Russian sidekick, Oleg (who videotapes everything and whose hero is Frank Capra), flee toward Central Park; and a fire marshal and a murder witness trying to escape from her apartment after it explodes in flames. Still, if it weren’t for the satire, I doubt that I would have been interested in seeing this picture again.

For the record, I enjoyed it just as much the second time, though it held up better as entertainment than as satire. Part of the reason may be that satire, even more than action, demands clarity and purity of purpose. By the time this movie gets to the homestretch, its attempt to combine a vitriolic anger at the media and the rabble-rousing, vigilantelike efforts of the fire marshal to defeat the villain is more than schizophrenic; by this point, the left hand barely seems to know what the right hand is doing.

Two movie satires that didn’t close in New Haven are Network (1976) and Forrest Gump (1994), neither of which attempted to double as a crime thriller. I suspect that one major reason they didn’t flop is that the targets in both movies — pushy feminists and cynical TV executives, ranting, hypocritical Black Panthers and fake hippie pacifists — are goonish, neocon cartoons, broader than barn doors and hence unthreatening to many in the audience. These movies were probably irritating only to grumpy liberals like myself who refused to accept that these strident parodies were accurate or ideologically neutral. Especially egregious were the supposedly sympathetic figures who reflected how the screenwriters (and presumably spectators) saw themselves: William Holden in Network is a “principled” middle-aged philanderer who can see through all the lies of the lefties while possessing nothing less than the Truth himself (a transparent and somewhat comical stand-in for Paddy Chayefsky in his 50s), and Tom Hanks in Forrest Gump is a saintlike, sweet-tempered, salt-of-the-earth moron who comically epitomizes the innate goodness of innocents everywhere (presumably an idealized version of screenwriter Eric Roth, novelist Winston Groom, or director Robert Zemeckis, each hankering after his lost childhood).

One could argue that the simplifications in 15 Minutes about ruthless TV producers and unethical lawyers aren’t much different, but you don’t have to be a liberal to find these caricatures fairly believable or their real-life counterparts fairly sickening. And even though the Russian videographer might be viewed as a Gump with a foreign accent, he and the even creepier Czech killer, both recent immigrants, are embodiments of our own worst impulses and tendencies, monsters whose excesses stem directly from their observations of us. Theoretically we couldn’t laugh at Gump without recognizing something of him in ourselves, and we’d be inclined to be affectionately indulgent about his foibles. Any laughter provoked by the Russian stooge is bound to be more troubled, because Oleg is clearly a kind of Frankenstein monster our culture has created and his innocence is far more dangerous.

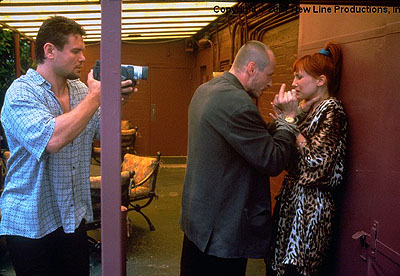

Roseanne Barr is one of the people thanked in this movie’s closing acknowledgments. It isn’t clear whether the segment of her touchy-feely daytime talk show — about a man who confesses to sleeping with his daughter-in-law, then, after she offers her own tearful confession, kneels on the floor and remorsefully hugs his son — is an actual clip or a simulation, though I don’t suppose it matters. More significant is that shots of Emil and Oleg watching this segment (which ends with a freeze frame and the title “Next up: forgiveness”) alternate with the footage Oleg has just taken with a stolen video camera of Emil stabbing to death his former partner and the partner’s wife.

Writer-director John Herzfeld implicitly treats these two segments as practically interchangeable bits of shameless, pornographic spectacle. The Roseanne segment is already commodified; the snuff video hasn’t yet been, but as a subsequent development in the plot implies — a bit hysterically and implausibly, unless one allows Herzfeld some satiric leeway — this is only accidental. The media are equally willing to put either spectacle on display, complete with hypocritical justifications, to boost ratings. From this standpoint, the stupidity of a Russian Gump, the venality of a sensationalist TV newscaster and of a lawyer who’s ready to defend anybody, and the connivance of a killer trying to get off on an insanity plea and then make another kind of killing by selling the movie rights, are all morally equivalent — it’s no wonder that all four scummy characters wind up striking various deals. Herzfeld underscores his point by having the media happily allow a mugger with a knife in Central Park to portray himself as a hapless victim speaking earnestly about kids’ need for role models.

This sort of misanthropy may not add up to a complex analysis, but it makes for a much more satisfying notion of villainy than we usually get in cop thrillers. It also suggests that two sets of genre cliches can be a lot better than one, especially if alternating between them throws the viewer off balance by objectifying aspects of the suspense with the satire and undercutting aspects of the satire with the suspense. (Herzfeld’s previous feature, the 1996 2 Days in the Valley, negotiated its own numerous miniplots with somewhat less irony, apart from a penchant for including dog reaction shots — a veiled comment about the good-natured slavishness of his audience?)

For all the confusing signals it generates, Herzfeld’s contradictory approach encourages thought and reflection — something few cop thrillers do. The dialectic between the genres parallels the contrast between the lead buddies — a media-friendly, middle-aged gumshoe (Robert De Niro) and a younger fire marshal who shuns the media (Edward Burns), slightly tetchy rivals who find themselves paired in the investigation of Emil’s murders. Which one is the hero? First you think it’s the cop — not only because it’s De Niro, but also because he practices proposing to his girlfriend in front of a mirror, a hokey bit of business clearly intended to remind us of Taxi Driver. But the real hero turns out to be the fireman, who gradually becomes so pissed off by the media that he becomes another potential psycho/avenging angel like De Niro’s heroically demented vet — a nutcase we’re meant to cheer for. Whoever the hero is, he’s not what you might call consistently heroic, but we’re still supposed to be on his side whenever he’s ready to commit murder.

Herzfeld winds up getting his own hands just as dirty as those of his four villains — and he dirties us in the process, though he doesn’t make it easy for us to overlook his or our duplicity. That’s what I like about 15 Minutes. It expands Warhol’s witticism to say, more or less, “In the future, everyone will be a world-famous psycho killer for 15 minutes, and everyone will also be a world-famous psycho killer’s victim for roughly the same amount of time. In this future democracy of fame and attention, where equal employment opportunities rule, trying to distinguish between stars and fans, cynical media perpetrators and gullible spectators, predators and victims, will be pointless.” Which is precisely my idea of satire.