Written for a collection edited by Adam Cook, Making the Case: Contemporary Genre Cinema, whose publisher belatedly changed his mind about publishing. This is the article’s first appearance, although it’s also reprinted in my latest book, Cinematic Encounters 2: Portraits and Polemics. — J. R.

Out of his half-dozen comedy features to date as producer-writer-director — Terms of Endearment (1983), Broadcast News (1987), I’ll Do Anything (1994), As Good as It Gets (1997), Spanglish (2004), and How Do You Know (2010) — James L. Brooks has had three big commercial successes (the first two and the fourth) and three absolute flops (the third, fifth, and sixth). And because all six of these movies are concerned equally with personal failure and personal success, functionality (emotional and professional) as well as dysfunctionality (emotional and professional), it somehow seems fitting that each one has represented a highly ambitious as well as a highly risky undertaking.

The above paragraph has the disadvantage of making Brooks seem so unexceptional as a commercial filmmaker that one might wonder, on the basis of this description, whether he’s worth examining at all. Some might also question whether all six of his movies qualify as comedies, despite Brooks’ own insistence that they do. (He’s even suggested that the comedy of Terms of Endearment represents his “solution” to the problem of how to make an entertaining movie about someone dying of cancer.) But arguably the only other assertion that might be considered questionable in my paragraph is the claim that they’re all “high-risk undertakings,” at least insofar as they all have bankable stars in them. Yet the real sticking point, especially among cinephiles, is whether they’re worthy of extended analysis. Because I consider them all profound, troubled, often contradictory, and endlessly fascinating autocritiques, I think they are.

A good illustration of how and why they usually aren’t can be found in the five-paragraph Brooks entry in the sixth edition of David Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary of the Cinema (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014). Thomson’s taste isn’t invariably mainstream — consider his enthusiasm for Jacques Rivette and his dislike of John Ford — yet one could argue that his popularity as a cinephile-pundit often rests on his capacity to engage with mainstream taste without seriously challenging it, and from this standpoint, his treatment of Brooks is exemplary. His first two paragraphs are devoted to praising with justifiable extravagance Brooks’ TV work: “Jim Brooks is living proof that American television, week after week, can deliver smart, well-written, beautifully played comedy series that are devoted to being decent and humane without seeming smug or idiotic. This is an extraordinary achievement, and one to be borne in mind whenever the mood takes us to think the worst of TV.” But before returning to this TV work in his third paragraph, here’s all he has to offer on Brooks’ first three features:

When he moved sideways, into feature films, he took Larry McMurtry’s novel [Terms of Endearment] and made a smart hit for which he won the Oscars for script, direction, and best picture. A few years later, Broadcast News was only a little less successful while being a tender portrait of the confusion and hypocrisy in doing TV. I’ll Do Anything is the least of his movies, but it was a musical once. When test screenings showed that it was failing with audiences, Brooks had the skills (and the freedom) to re-edit it. Nevertheless, it is his single large venture to result in disappointment.

Regarding the second three Brooks features, Thomson ignores Spanglish (which he omits from his Brooks filmography), skates past How Do You Know (which he adds a question mark to in the filmography), and regards As Good As It Gets as “another very effective social comedy for the big screen…which actually embodied TV ethics (be nicer to one another) and paired a movie Star (Jack Nicholson) with a TV star (Helen Hunt). It was a picture like soap in your hands — but, afterwards, you felt cleaner and better.”

But the most damning portion of Thomson’s critical summary is his preceding paragraph:

Brooks has spoken about trying to chart the urge toward decency, a mainstream subject one might suppose, yet one ignored by so much of Hollywood. There is a case to be made, I think, that Brooks remains unknown as a personality — he is a manager of good material, a producer who likes to make things work. He lacks the edge of, say, a Lubitsch or a Buñuel. But, of course, you say — whoever thought that American TV was open to such people? True enough, but then we have to face the fact that mass media may always move in search of a kind of anonymous, benevolent proficiency more suited to politicians than to artists.

Leaving aside the question of whether Lubitsch and Buñuel belong in the same category (or whether Lubitsch is really inimical to contemporary American TV), one of my underlying premises in everything that follows is that James L. Brooks is every bit as personally embedded in his features as Lubitsch or Buñuel are in theirs. Moreover, the fact that his personal presence and investment remains invisible to Thomson and many other cinephiles doesn’t mean that I’m the only one who thinks otherwise: in the 97th issue of the French quarterly Trafic, dated Spring 2016, Murielle Joudet’s provocative 18-page essay, “James L. Brooks, le secret magnifique”, even goes so far as to identify “a Brooksian touch” (“une touché brooksienne”) in such features as Alan J. Pakula’s 1979 Starting Over (which Brooks wrote and produced), and Penny Marshall’s 1988 Big and her 2001 Riding in Cars with Boys (both of which Brooks produced).

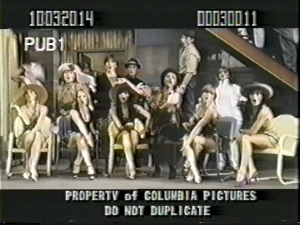

Furthermore, though I wouldn’t necessarily dispute Thomson’s claim that I’ll Do Anything, as released, is the “least” of Brooks’ movies to date, I would also argue that the original musical, which I’ve managed to see, is in many ways his most substantial and exciting achievement. (The slim likelihood that this will ever surface commercially is said to be a matter of costly song rights.) Therein lies the Brooksian paradox that I wish to explore here, tied in many ways to his success as cowriter and producer in TV comedy (e.g., The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Taxi, The Simpsons), where test-marketing might be said to play an even greater role than it does in Hollywood features. And it’s important to add that, in spite of what Thomson has to say about Brooks’ “skills” and “freedom” in re-editing that movie (which is largely and ironically concerned with Hollywood test-marketing, and in many respects can be regarded in part as a sort of west-coast “remake” of Broadcast News), the re-edited version grossed only slightly more than a fourth of the film’s total budget of $40 million (approximately double the budget of Broadcast News). This raises the question of whether the original musical version might have ultimately fared better. (We might also wonder what material we might have lost in other Brooks features; Spanglish reportedly went through thirteen previews.) For it’s a an axiom of movie test-marketing that it can test only immediate responses, not lingering impressions, and the undeniable strangeness of what Brooks was originally up to — which combined nine original songs by Prince and at least two others by Carole King and Sinéad O’Connor with twitchy choreography by Twyla Tharp — was the most obvious risk factor in that project.

***

For better and for worse, Brooks’ features are marked by his TV training. The negative side was noted by Dave Kehr in reviewing Terms of Endearment: “Brooks was one of the architects of the [Mary Tyler Moore] sitcom style, and he has television in his soul; his people are incredibly tiny (most are defined by a single stroke of obsessive behavior), and he chokes out his narrative in ten-minute chunks, separated by aching lacunae.” The positive side is the way that he orchestrates and juxtaposes his ten-minute chunks, single-trait portraiture, and stylistic overkill, yielding arresting, dialectical collisions that produce something richer than can be found in his sitcoms. The casualties of this approach — such as the overwrought , strident gargoyles of Jack Nicholson in As Good As It Gets and How Do You Know, and Tea Leoni in Spanglish — can’t be wished away, but neither can the fruitful collisions that they make possible.

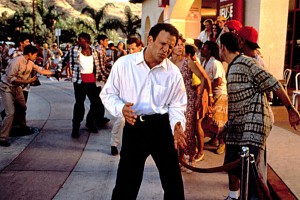

Broaching what makes all of Brooks’ features personal, it makes sense to start with Broadcast News and I’ll Do Anything because they’re the two whose subjects come closest to his own experience. (He began his career in television working for CBS News, and he has said, in reference to the years of research he usually spends in preparing his features, that I’ll Do Anything was the only one that required none.) In both films, he’s concerned with ethical issues involving talented people in media who fail (Albert Brooks in News, Nick Nolte in Anything) as well as succeed (William Hurt in News, Nolte’s character’s daughter Jeannie [Whittni Wright] in Anything), and equally concerned with talented successful people (Holly Hunter in News, Albert Brooks in Anything) with massive, neurotic personality disorders. Much of the plots in both films come from pitting these various types against one another dialectically, personally as well as professionally. Thus Albert Brooks’ Aaron in News, who sweats too much to succeed as an anchorperson and is romantically smitten with his best friend, Hunter’s Jane (who is attracted in turn to Hurt’s more camera-ready Tom), feeds ideas to Jane by phone during Tom’s news report on Libya, and Jane speaks into a concealed earpiece to Tom. (The complex means by which Aaron’s expertise gets translated into Jane’s editorial savvy, which is in turn translated into Tom’s charismatic delivery, is excitingly conveyed.) Nolte’s Matt in Anything fails his screen-test with Burke (Albert Brooks) but is hired as his part-time chauffeur and sleeps with Burke’s script-reader Cathy (Joely Richardson) — who has set up his screen-test, but winds up betraying him during its evaluation due to Burke’s hectoring — meanwhile befriending Burke’s mistress Nan (Julie Kavner) while his bratty little girl Jeannie, whom he mentors, succeeds in a sitcom that is then canceled.

The intricate webs of succeeding and failing professionally and/or personally in these worlds, set respectively in Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles, are far more elaborate, even in their dialectical crosscurrents, than these bald if breathless summaries can suggest, and the close relationship between these two worlds is even pinpointed in an early speech given by Nan in Anything that compares Washington to L.A.: “Both places have a lot in common: Overprivileged people crazed by their fear of losing their privileges. Alcoholism. Addiction. Betrayal. The near-total degradation of what once were grand motives. The same spiritual blood-letting.” And in keeping with Brooks’ ongoing ethical obsessions, these are basically the concerns of all his pictures. The fact that Burke and Jeannie figure as virtual doppelgängers illustrating Nan’s description only begins to account for their status as Brooksian staples.

“I conceived the story [of I’ll Do Anything] as a musical because musicals have a heightened sense of reality,” he has said. “Through song you can get closer to the truth.” In fairness to both Brooks and to test-marketing, I should concede that some of the musical numbers in the original I’ll Do Anything — such as two that are sung by Albert Brooks, including the title tune — fail both as memorable songs and as “truthful” expansions of the dramatic material. But the fact that all the numbers comprise logistical as well as aesthetic gambles, and ones which pay off in some other cases, is clearly what gives them part of their dynamic value. And the two that are, for me, the most affecting and powerful are the ones where dialectical forces are most hyperbolically at play: a production number devoted to actors hysterically rehearsing their auditions (punctuated by the contradictory mantras, “You’ve got to make believe!” and “It’s only a movie!”) and an even more emotionally wrenching and complex number in a chic restaurant where Nan is breaking up with Burke because of his compulsion to glad-hand all the other customers — her declaration given in a mournful song on the upper level (“I can’t love you anymore,/So I’m walking out the door…”) while his grotesquely cavorting behavior is seen below in comic choreography.

So it isn’t surprising that As Good As It Gets periodically evokes the hyperreality of musicals: Greg Kinnear’s gay Village painter calls to mind Gene Kelly in An American in Paris — a notion planted when he plays some of the Gershwin suite on his stereo — while Jack Nicholson’s neurotic writer noodling on his piano next door becomes a clear stand-in for Oscar Levant; and when the writer gets ejected for his boorish behavior by Helen Hunt’s waitress from a coffee shop and the other customers applaud, we still might be on an MGM soundstage, even if it looks like a real location.

Similarly, Nicholson’s monstrousness here and in three other Brooks films makes him the natural partner of another monster (Shirley MacLaine) in Terms of Endearment, and the veritable/virtual soul brother of such Brooksian misfits as Anything’s Burke and Spanglish’s Deb (Tea Leoni), to cite the only two films where he doesn’t appear. All these walking disasters periodically register as ferocious autocritiques of Brooks’ own obsessiveness as a filmmaker, and the fact that we wind up cherishing the witty putdowns they receive from their mates and/or family members (such as Cloris Leachman as Leoni’s mother in Spanglish) only intensifies the self-inflicted spiritual bloodletting. Even though Albert Brooks has confirmed that the ostensible model for Burke was Joel Silver, the man who wrote this character has also admitted that he was thinking partially of himself.

***

Even though only two of the Brooks features are about media, all of them are about performers who are conscious of performing and are continually critiquing and correcting their own and one another’s performances to each other. This process of compulsive revision becomes literalized in How Do You Know when a character named Al whom we barely know hands the hapless executive hero (Paul Rudd) a video camera to record his impromptu marriage proposal to his girlfriend — the hero’s former secretary and best friend, who has just given birth to their baby boy in a hospital. The hero’s own “performance” in recording Al’s speech fails because he forgets to hit the red button, so the proposal then has to be given a second time, with prompts from everyone else present, in a second “take”, this time correctly recorded. “We’re all just one small adjustment away from making our lives work,” this hero says to the heroine at the film’s climactic juncture, and it’s probably the closest Brooks has ever come to formulating an epigraph (or epitaph) to his cinematic oeuvre, which is obsessively composed of nothing but small adjustments. It’s the credo of an optimistic gambler and a compulsive reviser, recklessly going for broke.

If the trade papers are to be believed (a dubious concept in itself), Spanglish had a production budget roughly double that of I’ll Do Anything, and although it grossed over five times as much, it still lost money. By contrast, How Do You Know cost ten times as much as I’ll Do Anything and made slightly less than half of that budget back — which suggests that we may have to wait some time before a seventh Brooks feature comes along.

Without presuming to guess where and how all that money was spent, the subject and focus of both these features already earmark them as high-risk ventures: the experiences of a Mexican immigrant (Paz Vega) as a maid with the family of a wealthy chef (Adam Sandler) in Bel Air and Malibu, as recounted in flashback by her teenage daughter (Shelbie Bruce); a 31-year-old professional softball player (Reese Witherspoon) who loses her professional status because of her age and then has to choose romantically between a cheerful, promiscuous, self-involved pitcher (Owen Wilson) and a hapless but honest executive (Paul Rudd) who has just lost his job at the company run by his father (Jack Nicholson) after being targeted by a federal criminal investigation for a crime committed by his blustery dad. Spanglish was probably further hampered commercially by having a lot of unsubtitled Spanish dialogue (a language Brooks didn’t speak himself), and How Do You Know may have been further handicapped by appearing to deal with baseball while retaining only the barest minimum of sports footage. Both of these commercial liabilities point to Brooks’ seriousness in addressing his chosen topics, which have much more to do with ethical performance, familial obligation, romance, and class than they do with translingual communication, sports, or corporate crime.

Both News and Anything stage crises around moments when performers produce tears on-camera. In News, these tears are faked by Tom while giving a report about date rape, and Jane, his producer, about to run off with him on a tryst, changes her mind after she learns from Aaron about his fakery. In Anything, Jeannie knows she’ll be required to cry in the kids’ TV show she’s appearing in and is afraid she won’t be able to. Matt advises her to either think of something that makes her sad or to forget that she’s pretending; she opts for the former, enabling Matt to succeed finally in his futile efforts at parenting. In this case, producing tears is seen as unambiguously desirable (in contrast to Jeannie’s previous crying jags that manipulate her father) whereas in News it’s regarded as odious, but curiously, in neither case is the effect or quality of the TV show made an issue. This implies that Brooks is either rethinking his moral position or reasoning that authentic emotion matters in a news show but is irrelevant in a staged fiction (even if the kids watching it or the kid performing it may not grasp the difference). You might say he’s stuck in the existential dilemma of show biz itself and all that it entails, and whether he wills this or not, we’re stuck in the same conundrum. You might even say that vexing, ambiguous, and delicate ethical questions of this kind are what all his films are about. And in an era when reality TV and celebrity culture have yielded a Donald Trump, it’s hard to think of a subject more contemporary or relevant.