Commissioned by and written for a collection entitled Time, published in February, 2016 by Punto de Vista, Festival Internacional de Cine Documental de Navarra in Pamplona, Spain. — J.R.

Selected Moments: Some Recollections of Movie Time

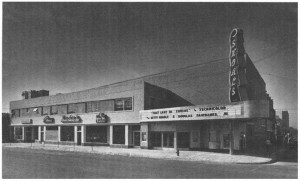

1. My first sixteen years (1943-1959) — growing up in northwestern Alabama as the grandson and son of Jewish movie theater exhibitors — ensured that time and cinema were alternately parallel and crisscrossing rivers that coursed through my childhood, along with the Tennessee River that separated Florence from Sheffield. Florence, where I lived, had three of the Rosenbaum theaters, at least until 1951, all within a three-block radius, while Sheffield, which I could see across the river from my back yard, had two more theaters, one around the corner from the other. For Southerners like myself, the past was always present, a kind of double vision that movies taught me as well — a camera’s recording of the past becoming the present of both a screen and an audience, which then in retrospective memory becomes the past as well. And for Jews like myself, the past was also identity — meaning one’s past, present, and future. This explains why Lanzmann’s Shoah represents a shotgun marriage between the present tense of existentialism and the past tense of Judaism.

1. My first sixteen years (1943-1959) — growing up in northwestern Alabama as the grandson and son of Jewish movie theater exhibitors — ensured that time and cinema were alternately parallel and crisscrossing rivers that coursed through my childhood, along with the Tennessee River that separated Florence from Sheffield. Florence, where I lived, had three of the Rosenbaum theaters, at least until 1951, all within a three-block radius, while Sheffield, which I could see across the river from my back yard, had two more theaters, one around the corner from the other. For Southerners like myself, the past was always present, a kind of double vision that movies taught me as well — a camera’s recording of the past becoming the present of both a screen and an audience, which then in retrospective memory becomes the past as well. And for Jews like myself, the past was also identity — meaning one’s past, present, and future. This explains why Lanzmann’s Shoah represents a shotgun marriage between the present tense of existentialism and the past tense of Judaism.

During my childhood, movies were a way of measuring time and time was a way of measuring movies, even if my easy access into most of the local theaters meant that my own time could easily and often did supersede the movie’s time. As was common for everyone during most of that period, I could go to the movies without specific schedules or timetables, sometimes entering in the middle of a feature and then staying to roughly the same point in the following screening of the same feature, or leaving temporarily in the middle of a film to buy a comic book down the street before returning. An additional privilege that I had, if I wanted to use it, was glancing inside the ticket-taker’s booth in the lobby — an “insider’s” look — to read the precise menu of feature(s) and shorts to be found later in the auditorium, complete with titles and running times. In a manner of speaking, you might say I was able to be inside and outside the film experience at the same time, a privilege afforded today by most digital home viewing. Back then, in a certain fashion, it made me a film critic long before I even knew what the term meant, and I even had a choice of entrances at a couple of theaters denied to ordinary patrons — staff entrances that led directly from my father and grandfather’s upstairs offices into the balcony at the largest Florence theater, the Shoals, which opened in 1948, or from their previous ground-floor offices towards the downstairs seats at the Princess.

Walking from either the street or the offices into the Princess or the Shoals meant stepping from Alabama time into movie time, where Alabama time was suddenly suspended. And movie time wasn’t necessarily or invariably different from literary time: only a few counties away, in Oxford, Mississippi — a dozen years before I was born, a year before he went to work for Howard Hawks in Hollywood — William Faulkner was writing my favorite novel, Light in August, which begins in and periodically reverts to the present tense, the immediacy of movie time: “Sitting beside the road, watching the wagon mount the hill towards her, Lena thinks, ‘I have come from Alabama: a fur piece. All the way from Alabama a-walking. A fur piece.’ Thinking although I have not been quite a month on the road I am already in Mississippi, further from home than I have ever been before. I am now further from Doane’s Mill than I have been since I was twelve years old”. Alfred Kazin’s lovely essay about the novel is called “The Stillness of Light in August,” but it doesn’t acknowledge that the novel’s stillness is cinematic, not photographic or painterly, and Faulkner clearly learned as much from movies as he did from Joseph Conrad (another cinematic writer).

Walking from either the street or the offices into the Princess or the Shoals meant stepping from Alabama time into movie time, where Alabama time was suddenly suspended. And movie time wasn’t necessarily or invariably different from literary time: only a few counties away, in Oxford, Mississippi — a dozen years before I was born, a year before he went to work for Howard Hawks in Hollywood — William Faulkner was writing my favorite novel, Light in August, which begins in and periodically reverts to the present tense, the immediacy of movie time: “Sitting beside the road, watching the wagon mount the hill towards her, Lena thinks, ‘I have come from Alabama: a fur piece. All the way from Alabama a-walking. A fur piece.’ Thinking although I have not been quite a month on the road I am already in Mississippi, further from home than I have ever been before. I am now further from Doane’s Mill than I have been since I was twelve years old”. Alfred Kazin’s lovely essay about the novel is called “The Stillness of Light in August,” but it doesn’t acknowledge that the novel’s stillness is cinematic, not photographic or painterly, and Faulkner clearly learned as much from movies as he did from Joseph Conrad (another cinematic writer).

This sense of cinematic literary time is no less evident in the beginning of the novel’s sixth chapter, plunging us into the consciousness and memory of the other major character, Joe Christmas, as metaphysical/ expressionistic and as cluttered with debris as Lena Grove’s is physical/ realistic and economically tidy: “Memory believes before knowing remembers. Believes longer than recollects, longer than knowing even wonders. Knows remembers believes a corridor in a big long garbled cold echoing building of dark red brick sootbleakened by more chimneys than its own, set in a grassless cinderstrewnpacked compound surrounded by smoking factory purlieus and enclosed by a ten foot steel-and-wire fence like a penitentiary or a zoo, where in random erratic surges, with sparrowlike childtrembling, orphans in identical and uniform blue denim in and out of remembering but in knowing constant as the bleak walls, the bleak windows where in rain soot from the yearly adjacenting chimneys streaked like black tears.” Cinematically speaking, Lena’s mind is like Rio Bravo and Joe’s is like Eraserhead. Or, in the literary terms of Erich Auerbach’s best essay (“Odysseus’ Scar”), Lena’s mind is Homeric and continuous (or, in Faulkner’s terms, “like something moving forever and without progress across an urn”), whereas Joe’s is as riddled with narrative gaps, unexplained motivations, and sudden leaps forward as the Old Testament.

Today, of course, digital home viewing has altered all these temporal options, so that my time now supersedes movie time. I can stop the movie and start it up again or reverse or fast-forward or freeze the flow, meanwhile altering the shape and size of the image, and Chicago time has relatively little to do with either my time or movie time–which is why I’m fond of saying that I live on the Internet, which has a time and flow of its own, and relatively speaking, only sleep and eat in Chicago.

How, then, can I explain or examine the rift between today’s home-digital movie time and my childhood’s theater-analog movie time, except to say that literary time has more to do with the latter than with the former? Today I can bookmark, scan, retrace, and even quote from my movies, as I’ve just quoted from Light in August, and furthermore feel far more qualified to call them mine because I can handle them like books — turning to favorite passages, skipping certain parts, or freezing their flow whenever I want to.

And in tracing the steps between Alabama and Illinois, between “Now and Then” (the title of my first published work in prose, significantly a tale about time travel), all that I can hope to do here is to list a few temporal way-stations within that yawning rift, a selection of diverse moments, places, and occasions involving movie time—or my own writing or reading at various times about movie time. (Note: all of my own texts quoted from here and some additional texts about all the works cited can be found in their entirety at jonathanrosenbaum.net.)

One effort of mine to navigate this background is my memoir Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), the longest chapter of which, “On Moonlight Bay as Time Machine,” runs through that Doris Day musical in order to access myself respectively at age eight, seeing the film for the first time at the Shoals in October 1951; myself at ten, reseeing it at a Jewish boys’ camp in Maine in July 1953; and myself at age 34, in December 1977, reseeing the film on a rented color TV in southern California while smoking a joint and taping the soundtrack on a cassette recorder, then playing the cassette back and writing about the film at diverse times over the following year. (The joint is worth mentioning because it subjectively slows time down.)

***

2. It was during my two years at a boarding school in Putney, Vermont (1959-61) that I first saw Citizen Kane, and during my year and a half at New York University (1961-62), before moving up the Hudson River to Bard College, that I first saw L’Année Dernière à Marienbad (again and again, over a single week) — two seminal and formative spatiotemporal encounters that fractured and scrambled conventional narrative time frames and spatial parameters, leapfrogging between and within shots, places, events, and mental spaces.

3. During most of my years at Bard (1962-66), running the Friday night film series, I booked and showed such films as Greed, Variety, Freaks, Trouble in Paradise, The Magnificent Ambersons, Ivan the Terrible, Ikiru, The Phenix City Story, Sawdust and Tinsel, This Sporting Life, Jules et Jim, and Zazie dans le métro — essentially conducting my own film history seminar long before such a course could or would have been offered academically at Bard, and meanwhile picking up what I could from these films about other periods and countries.

3. During most of my years at Bard (1962-66), running the Friday night film series, I booked and showed such films as Greed, Variety, Freaks, Trouble in Paradise, The Magnificent Ambersons, Ivan the Terrible, Ikiru, The Phenix City Story, Sawdust and Tinsel, This Sporting Life, Jules et Jim, and Zazie dans le métro — essentially conducting my own film history seminar long before such a course could or would have been offered academically at Bard, and meanwhile picking up what I could from these films about other periods and countries.

The only film I wound up screening twice at Bard was my favorite at the time, Murnau’s Sunrise, and one of its emotional high points for me was George O’Brien’s walk across the marshes at night towards his secret erotic rendezvous with Margaret Livingstone, accompanied by a camera movement that begins as purely physical and then suddenly rushes ahead of him through the thicket to become metaphysical, arriving at the appointed spot before he does. The lesson of this voluptuous transition was in part grammatical — the realization that just as a single sentence could move from the physical to the metaphysical, so could a camera movement within a single shot or take.

But it’s worth adding that a shot and a take aren’t precisely or necessarily the same thing, especially in relation to time and narrative as they’re perceived. Much of my schooling in the difference between the two came from the Nouvelle Vague of Godard, Rivette, and Truffaut and the critical dimension that informed their filmmaking, leading to an overall sense that they and not their characters were the true heroes of their films. And part of their heroism came from their metaphysical appreciations of American physicality, which influenced an entire generation of subsequent American critics (myself undoubtedly included).

Andrew Sarris once argued (in 1966) that the slow lap dissolves in Josef von Sternberg’s The Docks of New York “serve the same function as Godard’s jump cuts in Breathless, and that is to indicate the meaninglessness of the time intervals between moral decisions.” This is existentialism with a vengeance, ignoring the musical as well as physical differences between slow dissolves and fast cuts for the sake of moral and metaphysical blueprints, and I think it could be argued that this type of reasoning is profoundly American in its implicit privileging of transcendental and symbolic meanings over material realities. (The same sort of impulse has made it impossible for American mainstream discourse to cope with the notion of a Barack Obama — or a Joe Christmas — who is half white and half black, existentially limiting their identities to black by default in both cases. And of course the very terms “white” and “black” to describe these people are more symbolic than physically descriptive.)

4. First encountering Tati’s PlayTime as an American tourist in Paris in 1968, before moving more permanently to that city from New York the following year, I was struck by how successfully the film managed to encapsulate the events of an entire day in only two hours without any obvious ellipses. Like a magician’s sleight of hand, this becomes a trick of implied temporal continuity that is gently imposed over the multiple spatial discontinuities created by architectural uniformity and the diverse confusions of glass reflections and competing focal points. One way in which this film gradually teaches me how to live in cities is its lesson in how to look creatively, carving one’s own spatial symmetries and counter-balances out of the chaos of sensory overload that assaults us whenever we’re walking down a city street. The film gradually evolves in terms of gazes and other human movements from regimented straight lines and right angles into playful and spontaneous curves and circles, with the film’s populace developing in the same fashion, much as the music that we hear gradually evolves from tunes in 4/4 time to waltzes. In fact, the gift of music is what makes this liberation possible by turning one’s own exploratory glances into impromptu dance movements.

4. First encountering Tati’s PlayTime as an American tourist in Paris in 1968, before moving more permanently to that city from New York the following year, I was struck by how successfully the film managed to encapsulate the events of an entire day in only two hours without any obvious ellipses. Like a magician’s sleight of hand, this becomes a trick of implied temporal continuity that is gently imposed over the multiple spatial discontinuities created by architectural uniformity and the diverse confusions of glass reflections and competing focal points. One way in which this film gradually teaches me how to live in cities is its lesson in how to look creatively, carving one’s own spatial symmetries and counter-balances out of the chaos of sensory overload that assaults us whenever we’re walking down a city street. The film gradually evolves in terms of gazes and other human movements from regimented straight lines and right angles into playful and spontaneous curves and circles, with the film’s populace developing in the same fashion, much as the music that we hear gradually evolves from tunes in 4/4 time to waltzes. In fact, the gift of music is what makes this liberation possible by turning one’s own exploratory glances into impromptu dance movements.

5. In the first of my Paris Journals written for Film Comment, (Fall 1971), published almost halfway through my five years in that city (1969-74), the two films that excited me most, both of which I was belatedly catching up with at the time, were two tales about encroaching madness, Jean-Daniel Pollet’s 37-minute Le Horla (1966) and Jacques Rivette’s 252-minute L’amour fou (1968), each of which excelled in a different way through its treatment of time.

Regarding the first, “Pollet has indicated in an interview that his interest in the project was not so much De Maupassant’s horror story itself but the problem of integrating the text into a cinematic structure. Part of his solution is to maintain a fluid continuity in the spoken first-person narration while locating this discourse through montage in three alternating ‘relative’ tenses: past (the plot unfolding beneath the narration), present (the narrator recounting the action into a tape recorder), and future (the tape recorder playing his voice in an abandoned rowboat). Thus while the story’s chronology and continuity are respected, the montage enables the film to achieve a semi-autonomous achronological structure of its own, and the tensions between these coexisting forms produces some extraordinary effects — effects, moreover, which serve the original story admirably, enclosing its intimations of possession and madness in a rigid continuum of haunting finality. Equally striking is a bold thematic use of color, with the richest blues this side of Pierrot le fou.” Even more, the solitary hero’s crazed intimations of an invisible doppelgänger lurking nearby and waiting to replace him, even reading the same texts over his shoulders, are neatly replicated by the camera’s own positions and activities, and the hero’s fear of being supplanted by the monster seems borne out by the way that the tape recorder replaces Laurent Terzieff in the otherwise empty rowboat.

Bulle Ogier’s monologues into a tape recorder in L’amour fou are no less unsettling, but in this case the main temporal issue is duration rather than tense — the consequences of living with the principal characters for over four hours — and the main source of visual contrast is the oscillation between 16-millimeter and 35-millimeter during the theater rehearsals. In both of these seminal film experiments, the shifts between recording mechanisms disrupt the transparency of what’s being recorded, so that our grasp of any firm distinction between storytelling and subject becomes as unhinged as our grasp of the differences between sanity and madness. (In Light in August, a comparable form of madness known as racism arises from the inability of determining whether Joe Christmas is “white” or “black”, an abstraction in either case—which forces us to acknowledge that “sanity”, “insanity”, “white,” and “black” are ultimately social definitions, not material attributes.)

6. From “Gertrud as Nonnarrative: The Desire for the Image” (Sight and Sound, Winter 1985-86): “There are narrative and nonnarrative ways of summing up a life or conjuring a work of art, but when it comes to analyzing life or art in dramatic terms, it is usually the narrative method that wins hands down. Our news, fiction, and daily conversations all tend to take a story form, and our reflexes define that form as consecutive and causal — a chain of events moving in the direction of an inquiry, the solution of a riddle. Faced with a succession of film frames, our desire to impose a narrative is usually so strong that only the most ruthless and delicate of strategies can allow us to perceive anything else.

“Carl Dreyer allows us to perceive something else, but never without a battle. The nonnarrative specter that haunts the narrative of Gertrud (1964), contained in the figure of Gertrud herself, is threatened at every turn by dogs snapping at her heels — a narrative world of men with pasts and futures who stake a claim on her. But Gertrud, who lives only in a continuous present, persistent and changeless, eludes them all. And if she eludes us as well, this may be because our narrative equipment can read her only as a monotone — an arrested moment (as in painting) or a suspended moment (as in music) that can lead to no higher logic. Yet from the vantage point of her refusal to inquire, she has a lot to say to the men.”

7. Another film that superimposes past over present within the same shots is Françoise Romand’s highly unorthodox TV documentary Mix-up (1985), tracing the extended repercussions on two extended families of an accidental mix-up of babies in an English hospital in the 1930s and the confirmation of this error only three decades later. Because various stages in this long narrative are made to coexist in the present, the plot and characters eventually register with the density of a 500-page novel. And the subject is treated so exhaustively that the film’s 63 minutes register like a much longer film. Interviewing virtually all the members of both families, including the daughters who grew up with the wrong parents, Romand also restages some key scenes in the midst of these interviews, conducting a sort of collective psychoanalysis, so that when one brother “crouches as an adult under a table to describe a conversation he overheard under the same table at age 13, the moment is uncanny.” (Sight and Sound, October 2010).

7. Another film that superimposes past over present within the same shots is Françoise Romand’s highly unorthodox TV documentary Mix-up (1985), tracing the extended repercussions on two extended families of an accidental mix-up of babies in an English hospital in the 1930s and the confirmation of this error only three decades later. Because various stages in this long narrative are made to coexist in the present, the plot and characters eventually register with the density of a 500-page novel. And the subject is treated so exhaustively that the film’s 63 minutes register like a much longer film. Interviewing virtually all the members of both families, including the daughters who grew up with the wrong parents, Romand also restages some key scenes in the midst of these interviews, conducting a sort of collective psychoanalysis, so that when one brother “crouches as an adult under a table to describe a conversation he overheard under the same table at age 13, the moment is uncanny.” (Sight and Sound, October 2010).

8. “It’s obvious that most of us watch films while we’re seated. But just because it’s obvious doesn’t mean that it isn’t worthy of some reflection — and reflection, after all, is something else that’s often best done while we’re sitting. Yet the artificial sensation of speed that characterizes so much of contemporary commercial cinema, American cinema in particular — the speed of fast cars and explosions and what we call ‘action’, not to mention the speed of much TV editing, all of which tends to make Ozu seem ‘conservative’ and ‘old-fashioned’ by comparison — tends to deny this fact, to operate as if we were literally watching films on the run, without any opportunities for reflection.

8. “It’s obvious that most of us watch films while we’re seated. But just because it’s obvious doesn’t mean that it isn’t worthy of some reflection — and reflection, after all, is something else that’s often best done while we’re sitting. Yet the artificial sensation of speed that characterizes so much of contemporary commercial cinema, American cinema in particular — the speed of fast cars and explosions and what we call ‘action’, not to mention the speed of much TV editing, all of which tends to make Ozu seem ‘conservative’ and ‘old-fashioned’ by comparison — tends to deny this fact, to operate as if we were literally watching films on the run, without any opportunities for reflection.

“Ozu’s acknowledgment that we watch films while sitting seems to me a fundamental aspect of his style, and a great deal that is considered difficult or problematical or simply ‘slow’ in his style derives from this essential fact. As a rule, characters in Ozu films are seated when they eat and when they converse. In I was Born, But…, the two little boys who are the central characters are mainly seen on their feet, but early in the film they are seated when they have breakfast, when they put on their shoes before leaving their house, and then when they decide to skip school and have their lunch in a field. They are also seated when they attend school the following day, when they watch home movies at the home of the father’s boss, and later, after their fight with their father, when they refuse to eat. All of these occasions might be described as times of relative reflection.

“But this is a film in which social behavior and social conditioning are at least as important as reflection, and the issue of speed is relevant to all three activities. Early in the film, after the boys skip school out of fear of getting beaten up and have their lunch in the field, one of the brothers reminds the other, ‘We’re supposed to get an A in writing today.’ Soon afterwards they both stand up to finish their lunch on their feet, an action which implies, as much else in the film does, that getting ahead in the world requires alertness and motion, both of which are usually more obtainable from a standing position.” (From “Is Ozu Slow?”, a lecture delivered at a symposium, “Yasujiro Ozu in the World,” in Tokyo, December 11, 1998.)

“But this is a film in which social behavior and social conditioning are at least as important as reflection, and the issue of speed is relevant to all three activities. Early in the film, after the boys skip school out of fear of getting beaten up and have their lunch in the field, one of the brothers reminds the other, ‘We’re supposed to get an A in writing today.’ Soon afterwards they both stand up to finish their lunch on their feet, an action which implies, as much else in the film does, that getting ahead in the world requires alertness and motion, both of which are usually more obtainable from a standing position.” (From “Is Ozu Slow?”, a lecture delivered at a symposium, “Yasujiro Ozu in the World,” in Tokyo, December 11, 1998.)

9. “The Clock is certainly dumb: a 24-hour movie made entirely from other movies in which the depicted screen time corresponds precisely to the actual time of the screening with plenty of clock inserts and shots in which clocks appear, sometimes incidentally. I’m sure I’m not the first to ask, why didn’t I think of that? But is The Clock dumb enough?” (Thom Andersen, “Random Notes on a Projection of The Clock by Christian Marclay at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 4:32 pm, July 28, 2011-5:02 pm, July 29, 2011” (Cinema Scope, Fall 2011).

10. A few other things I could have discussed: films involving real time and long takes (e.g., Robert Frank’s 1990 One Hour, Béla Tarr’s 1994 Sátántangó, László Nemes’ Son of Saul — all three masterpieces); Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour, Je t’aime, Je t’aime, Providence, and Mélo (among many others); evocations of cosmic time in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker (1937), and the 2014 TV series Big History; and implications of psychoanalytical time in the first four films of Peter Thompson (1982 and 1986).

10. A few other things I could have discussed: films involving real time and long takes (e.g., Robert Frank’s 1990 One Hour, Béla Tarr’s 1994 Sátántangó, László Nemes’ Son of Saul — all three masterpieces); Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour, Je t’aime, Je t’aime, Providence, and Mélo (among many others); evocations of cosmic time in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker (1937), and the 2014 TV series Big History; and implications of psychoanalytical time in the first four films of Peter Thompson (1982 and 1986).