Written in May 2014 for De Lumière a Kaurismäki: La clase obrera en el cine, coedited by Carlos F. Heredero and Joxean Fernández and published by Colección Nosferatu in 2014. — J.R.

Writing about the reception of Brecht’s Threepenny Opera in pre-Hitler [1928] Germany, Hannah Arendt noted (in The Origins of Totalitarianism) that “The play presented gangsters as respectable businessmen and respectable businessmen as gangsters. The irony was somewhat lost when respectable businessmen in the audience considered this a deep insight into the ways of the world and when the mob welcomed it as an artistic sanction of gangsterism. The theme song in the play, “Erst kommt das Fressen, dann kommt die Moral [First comes food, then comes morals],” was greeted with frantic applause by exactly everybody, though for different reasons. The mob applauded because it took the statement literally; the bourgeoisie applauded because it had been fooled by its own hypocrisy for so long that it had grown tired of the tension and found deep wisdom in the expression of the banality by which it lived; the elite applauded because the unveiling of hypocrisy was such superior and wonderful fun. The effect of the work was exactly the opposite of what Brecht had sought by it.”

My subject is “the presence and/or the protagonist of the working class in the American cinema of the Great Depression and the New Deal” (during the 30s and early 40s), so why am I evoking the German responses to a German play a couple of years prior to this period? Basically because the perception of class in the U.S. — often clouded by intimations of the American Dream that are tied to a faith in social mobility and feelings of shame or embarrassment about being poor, and frequently confused with or hidden behind associations of class with culture and style — can be best approached indirectly, through the distortions and inflections of that confusion, and because, as Brecht apparently discovered in 1928 Germany, intentionality in matters of art in any culture or period is always a hazardous matter. And, most of all, because it is the experience of working-class reality shared by artists and audiences in this period, filtered through both perceptions and fantasies about business, crime, everyday life, war, and strife, that I wish to examine rather than any unfiltered depiction of that reality in movies, which is much harder to locate or describe. Indeed, apart from the portrayals of working-class characters and their jobs in slapstick comedies — most notably, in Chaplin’s City Lights and Modern Times and in the shorts and features of Laurel and Hardy — signs of that reality in Hollywood pictures tended to be infrequent and/or marginalized. The exceptions and the reasons for their being exceptional are both worth noting: the first three American films of Fritz Lang, for example, which might be called his Sylvia Sydney trilogy — Fury (1936), You Only Live Once (1937, see still below), and the neglected and underrated You and Me (1938), the most Brechtian of all his films — are directly focused on struggling working-class couples who are hoping to get by rather than become rich. Although there are other such couples to be found in American films of the Depression, when survival rather than social advancement was becoming a pressing concern, the overall pessimism of Lang’s vision makes these films seem more “European” than most of the others, which typically refused to relinquish the American Dream’s inherent optimism.

Most Americans went to movies in the 30s to escape from their worries, including in many cases the jobs they didn’t have, so focusing on working-class characters who were working was not a way of encouraging them to spend much of their time in cinemas. This was even more apparent in depictions of the working-class in relation to the New Deal, which were found exclusively in independently made shorts and documentaries such as Pare Lorentz’s The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936) and The River (1937), Sidney Meyers and Jay Leyda’s The People of the Cumberland (1937), Ralph Steiner’s The City (1939), Robert Flaherty’s The Land (1940), Joris Ivens’ Power and the Land (1940), and, perhaps the most radical of them all, Leo Hurwitz and Paul Strand’s Native Land (1942). Hollywood studios were typically in competition rather than in cahoots with the U.S. government and were more interested in entertaining the audience than in instructing or politicizing them, at least according to their conscious designs.

According to Carlos Clarens in Crime Movies: An Illustrated History (1980), “A Chicago poll in 1931 disclosed that Hollywood stars and Chicago mobsters topped the list of best-known personalities on the American scene; as a life choice, stardom and grand-scale crime loomed equally out of reach for the average man, as if stars and public enemies existed on a different plane of achievement, creatures of a separate fate.” Due to the combined impact of the Stock Market Crash and Prohibition, this “separate fate” must have seemed like the two likeliest or at least most obvious ways of getting ahead. And in keeping with this folk wisdom, working-class characters were not what most audiences wanted to see, even as identification figures, unless they were tied in some fashion to gangsters and/or stars of the stage or screen — or at least to performers (as in such uncharacteristic yet potent examples as Freaks and Sylvia Scarlett). Consequently, the coexistence of these role models in Hollywood movies seems like a helpful starting point, especially when it comes to such gangster films as The Public Enemy (William A. Wellman, 1931), Little Caesar (Mervyn LeRoy, 1931), Scarface (Howard Hawks, 1932), and Rowland Brown’s Quick Millions (1931) and Blood Money (1933), all of which essentially equated a life of violent crime with “getting ahead”, much as the memorable Baby Face (Alfred E. Green, 1933) equated the prostitution of Barbara Stanwyck’s working-class character with economic advancement. But the coexistence of perceptions and fantasies about what it meant to be working-class in those movies seems equally relevant.

In the musicals that became popular at Warners — the most working-class in orientation of the major studios — the most persistent image of workers working was that of chorus girls tirelessly and desperately rehearsing their dance routines. And it seems that the evocation of working-class men, especially in musicals and crime pictures, often came through most vividly, if indirectly, through the recurring image of jobless war veterans — not just the figure of the “forgotten man” in Busby Berkeley’s famous “Remember My Forgotten Man” sequence in Gold Diggers of 1933 (Mervyn LeRoy), but also the hero played by Paul Muni in I Was a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (Mervyn LeRoy, 1932), an old timer in The Petrified Forest (Archie Mayo, 1936), and the leading characters played by James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart (along with some secondary characters) in The Roaring Twenties (Raoul Walsh, 1939), as well as the hero (Richard Barthelmess) in Heroes for Sale (William A. Wellman, 1933). Part of this relates to the alleged (and relative) classlessness of military service, a situation reflected in some of the ironies maintained in Three Comrades (Frank Borzage, 1938), but a more important part relates to a historical memory in the 30s that tends to be forgotten today. In the spring and summer of 1932, 17,000 jobless World War I veterans, their families, and various supporters gathered in Washington, D.C. to demand immediate cash-payment redemptions for their service certificates, a movement labeled the Bonus March in the news. In late July, these demonstrators were ordered by the attorney general to leave, several were killed in the subsequent skirmishes with police, and President Herbert Hoover ordered the army, led by Douglas MacArthur with six tanks, to drive out the veterans and their families, and their shelters and belongings were burned. Although a second and smaller march in the early part of the Franklin Roosevelt administration was defused in May 1933 with the offer of government jobs, and in 1936 Congress finally agreed to pay the veterans their demanded bonuses, overriding Roosevelt’s veto, bitter memories of the 1932 events lingered in the public imagination, and found expression in such films as Gabriel Over the White House (Gregory La Cava, 1933). Yet significantly, by the time of La Cava’s comedy My Man Godfrey (1936), the term “forgotten man” was employed to refer to the jobless title hero (William Powell), a former millionaire who gets hired by a wealthy family as a butler and who apparently isn’t a war veteran at all; similarly, when “forgotten man” turns up in the lyrics of one of the songs in You and Me (1938), the connotations of “war veteran” are elided.

In the musicals that became popular at Warners — the most working-class in orientation of the major studios — the most persistent image of workers working was that of chorus girls tirelessly and desperately rehearsing their dance routines. And it seems that the evocation of working-class men, especially in musicals and crime pictures, often came through most vividly, if indirectly, through the recurring image of jobless war veterans — not just the figure of the “forgotten man” in Busby Berkeley’s famous “Remember My Forgotten Man” sequence in Gold Diggers of 1933 (Mervyn LeRoy), but also the hero played by Paul Muni in I Was a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (Mervyn LeRoy, 1932), an old timer in The Petrified Forest (Archie Mayo, 1936), and the leading characters played by James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart (along with some secondary characters) in The Roaring Twenties (Raoul Walsh, 1939), as well as the hero (Richard Barthelmess) in Heroes for Sale (William A. Wellman, 1933). Part of this relates to the alleged (and relative) classlessness of military service, a situation reflected in some of the ironies maintained in Three Comrades (Frank Borzage, 1938), but a more important part relates to a historical memory in the 30s that tends to be forgotten today. In the spring and summer of 1932, 17,000 jobless World War I veterans, their families, and various supporters gathered in Washington, D.C. to demand immediate cash-payment redemptions for their service certificates, a movement labeled the Bonus March in the news. In late July, these demonstrators were ordered by the attorney general to leave, several were killed in the subsequent skirmishes with police, and President Herbert Hoover ordered the army, led by Douglas MacArthur with six tanks, to drive out the veterans and their families, and their shelters and belongings were burned. Although a second and smaller march in the early part of the Franklin Roosevelt administration was defused in May 1933 with the offer of government jobs, and in 1936 Congress finally agreed to pay the veterans their demanded bonuses, overriding Roosevelt’s veto, bitter memories of the 1932 events lingered in the public imagination, and found expression in such films as Gabriel Over the White House (Gregory La Cava, 1933). Yet significantly, by the time of La Cava’s comedy My Man Godfrey (1936), the term “forgotten man” was employed to refer to the jobless title hero (William Powell), a former millionaire who gets hired by a wealthy family as a butler and who apparently isn’t a war veteran at all; similarly, when “forgotten man” turns up in the lyrics of one of the songs in You and Me (1938), the connotations of “war veteran” are elided.

In his exemplary book We’re in the Money: Depression America and its Films (1971), Andrew Bergman, the future screenwriter (Blazing Saddles) and writer-director (So Fine, The Freshman), who is particularly sharp in citing many of the political and ideological dodges of Hollywood pictures of this period in relation to social consciousness — rightly singling out King Vidor’s 1934 Our Daily Bread as “unique in expressing a need for escape from some unreal assumptions about life and work prevalent in an increasingly concentrated political and economic order,” and helpfully detailing many of the institutional barriers this film had to circumvent in order to get made at all — identifies the “shyster” (crooked lawyer or politician) as an emblematic figure of urban corruption in many key Hollywood movies. No less emblematic was the con-artist and confidence man, played most memorably by James Cagney in such Warners pictures as Blonde Crazy, Hard to Handle, Picture Snatcher, Lady Killer, and Jimmy the Gent — a charismatic, street-smart punk contriving to climb to the top with whatever swindle he can dream up, and usually retaining the audience’s sympathy en route because his wealthier targets are invariably shown in a far less sympathetic light. Cagney was too skillful and inventive a performer to ever play the same character twice, but a common trait in all these characters was a certain form of creative energy in dreaming up scams (one of which, significantly, was “hiding out” from the law by actually becoming a Hollywood movie star, in Lady Killer). In Hard to Handle (Mervyn LeRoy, 1933), perhaps the most cynically exuberant of these pictures, the universe that Cagney’s hero, Lefty Merrill, swims through is so relentlessly corrupt that dishonesty quickly becomes the only recognized means of survival, and the only character of any importance who has a legitimate job — his romantic rival for winning over the heroine — automatically becomes a figure worthy of scorn and ridicule. And in Jimmy the Gent (Michael Curtiz, 1934), where Cagney plays a crude racketeer who specializes in “finding” (i.e., counterfeiting) heirs to unclaimed fortunes, trying to win back the affection of a former secretary (Bette Davis) now working for a “straight” lawyer (Alan Dinehart) who appears to be finding heirs more legitimately. But as she and we eventually discover, the principal difference between the two con artists is a matter of professional style — serving tea and handing out copies of Vanity Fair to clients in the waiting room.

All these films are essentially celebrations of bluff, and the same applies to the opening of Frank Borzage’s exquisite Man’s Castle (1933, see above still) — a film that may be better known today in Spain than elsewhere because the only commercial DVD of it available is Fueros Humanos — where Spencer Tracy, dressed in a tuxedo, treats a starving Loretta Young, whom he meets in a park, to a lavish meal before revealing to the manager than he’s one of the eight million Americans currently out of work and revealing to Young that he’s able to wear a tuxedo, which he doesn’t own, only because it’s part of an advertising gimmick. And his brashness and bluff aren’t just a matter of tricking those with money; he’s equally willing to forge Babe Ruth’s autograph on a baseball that he gives to a needy boy (Dickie Moore). Despite his wanderlust, his ultimate allegiance is to whomever he perceives as part of his community (which is mainly other poor people living in adjacent shacks) and his putative family (Young, carrying their expected child, who joins him in a boxcar going to nowhere in particular, in the final scene) — with the sole exception of a self-centered and stereotypical villain significantly called Bragg (Arthur Hohl).

The sense of community conveyed in this film and the earlier Tracy vehicle Me and My Gal (Raoul Walsh, 1932), where he plays a neighborhood cop, fully bears out an observation once made by film critic Manny Farber while comparing the human iconography of movies in the 30s and the 70s, that in the 30s “every shape was legitimate” — you could be fat, short, or even one of the title leads in Freaks, and still be OK, still be taken as an ordinary person. In an exuberant low-budget romp like Sailor’s Luck (Walsh, 1933), we casually encounter working-class characters who are Italian, Jewish, gay, drunk, and/or Eastern European; virtually all of these figures are stereotypes of one kind or another — Walsh films are never “politically correct” — and most are periodically mocked for their stereotypical traits, yet they’re all accepted as integral parts of the urban community and social landscape. In a typical 30s film of this kind, you don’t have to look for identity in some organizational abstraction like ethnicity or correct body shape; most often, just being human is enough. And having the right kind of personal style always counts for more than one’s purchasing power.

A confusion of class with style and dress code exploited by Tracy’s hero in the opening of Man’s Castle is no less central to the Depression comedies of Ernst Lubitsch at Paramount, with the key difference that the leading characters in those films are seen most often in sleek European settings, regardless of where they come from in terms of class. Significantly, Trouble in Paradise (1932, see first still above), the sleekest of the Lubitsch comedies, opens with a Venice gondolier emptying garbage, and the romantic couple we meet soon afterwards, played by Herbert Marshall and Miriam Hopkins, are struggling jewel thieves pretending to be upper-class types. One might even say that their personal style becomes their class, which is even the case for the “gentleman” jewel thief played by William Powell (again, opposite Kay Francis as a wealthy victim and romantic partner) in William Dieterle’s neglected Jewel Robbery (see second still above), released by Warners earlier the same year. In both these films, our comic scorn is reserved for the upper-class or working-class types who lack the elegance of the romantic leads — stuffy suitors and a pompous family retainer in Trouble in Paradise, dull high-society types and a clueless night watchman and chief of police (both pacified into giggles with marijuana joints) in Jewel Robbery — while the servants, apart from Kay Francis’s mumbling butler in Trouble in Paradise, are basically ignored and/or treated as part of the décor.

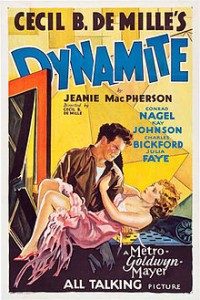

One indirect way of depicting the working class as a class was by focusing on children, in such films as The Mayor of Hell (Archie Mayo and an uncredited Michael Curtiz, 1933) and Wild Boys of the Road (William A. Wellman, 1933), and in Rowland V. Lee’s beautiful and neglected Zoo in Budapest (1933), even the exploited zoo animals might be said to serve a similar function. But there also a few outstanding films which pit the wealthy and the poor against each other in a stark and uncompromising matter, such as Cecil B. De Mille’s overlooked but potent first talkie, Dynamite (1930). Drawn from three separate news stories, the plot contrives to have a sophisticated city heiress (Kay Johnson) marry a coal miner (Charles Bickford) on the eve of his execution for a crime he didn’t commit so that she can inherit a fortune and thereby “purchase” a husband from a friend her own social set by persuading her to divorce him. Then, after the coal miner gets saved from the gallows at the last minute, she has to live with him as a pretended housewife in a mining village in order to receive her inheritance. Part of this is played as comedy, but the most remarkable thing about De Mille’s handling of the subject is his treatment of both the heiress and the coal miner with equal amounts of critical respect.

Frank Capra’s The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933) and It Happened One Night (1934), arguably his two greatest films, plot out equally improbable romantic encounters between a Chinese warlord (Nils Asther) and a working-class missionary (Barbara Stanwyck) in the first film, and between a spoiled heiress (Claudette Colbert) and a newspaperman (Clark Gable) in the second, with equally dynamic results. But perhaps the most cosmically dialectical couplings of this kind are found in my two favorite eccentric musicals of the period, Love Me Tonight (Rouben Mamoulian, 1932) and Hallelujah I’m a Bum (Lewis Milestone, 1933), both cinematic as well as ideological tours de force with Rodgers and Hart scores. In the first, a Parisian tailor (Maurice Chevalier) impersonating a baron winds up with a fairy-tail princess (Jeanette Macdonald); in the second, the “mayor” (Al Jolson) of the homeless tramps in Central Park winds up briefly with the mistress (Madge Evans) of the mayor of New York (Frank Morgan). The former is a Lubitsch-style fantasy while the latter is bracketed as a sort of accident (the mistress suffers amnesia, like the millionaire in City Lights, until she belatedly recovers her class and her senses) occurring within an even more outlandish fantasy in which the two mayors are best friends. But the latter is also still sufficiently “contemporary” to include in its cast of hobos a Trotskyite trash collector played by Harry Langdon.