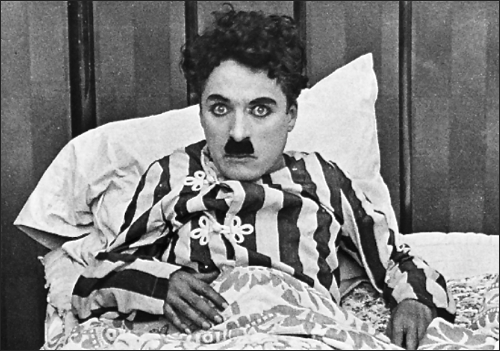

I was interviewed by Estado de Minas, the largest newspaper in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, shortly before and in connection with my plans to teach a ten-hour course on Charlie Chaplin there in mid-August 2012. (They ran some of my comments on criticism but omitted what I had to say about Chaplin.) Here are their questions and my responses….The first photo below shows Chaplin in a London film studio with Cy Endfield (on the left). — J.R.

1. Questions about Chaplin:

Why do we still love Charlie Chaplin? What makes him so relevant in 2012?

These are questions that I hope my course will help to answer. Right now, one of my main reasons for wishing to teach this course is that I don’t know the answers to these questions.

Why do you think Chaplin must be reintroduced to contemporary filmgoers? Isn’t he universally recognized and understood enough already?

It would be presumptuous of me to speak about whether or not Chaplin is adequately recognized today in Brazil —or, for that matter, in any country that I haven’t visited and/or whose language I neither speak nor read. But to make a generalization based on my experience, I would say that Chaplin tends to be universally recognized today as a great performer, but very widely unrecognized, undervalued, and misunderstood as a filmmaker. Consequently, I suspect that I’ll wind up having more to say about the latter aspect of his work than about the former.

Does film history omit or neglect what Charlie Chaplin represents?

Yes, because as the late novelist and critic Gilbert Adair used to say, “Chaplin doesn’t belong to film history; he belongs to history.” According to Adair, Chaplin was even greater than the cinema.

Which lessons does Charlie Chaplin’s cinematography give to contemporary moviemakers?

Above all, I think these are lessons of honesty and precision. Jean-Marie Straub has argued, provocatively, that Chaplin was the greatest film editor in all of cinema because he knew precisely when a gesture started and when it ended. Most contemporary moviemakers that I’m familiar with don’t understand this lesson nearly as well as Chaplin did. And it’s hard to think of many others who are more honest about the way they view both the world and themselves, even when this causes problems with their audience. Another major part of this honesty is, of course, about what it means to be poor. I can think of few other artists in any medium who are more eloquent and informative about this subject.

2. Questions about film criticism:

You’ve said that film criticism is one of the most ephemeral of literary genres. In this case — understanding film criticism not only as a literary genre, but also as a journalistic genre — why do we still read reviews published in the past?

We obviously should, but we don’t do this nearly enough—just as we don’t see older films nearly as much as we should. What sort of view would we have of literature if this were restricted to contemporary books that we can buy in supermarkets? This is the view, alas, that most people have of cinema. And what sort of view can we have of film criticism if this is restricted to reviews of current films? It’s important to add that film criticism can’t and should never be restricted to reviews.

Why? For you, what is the diference between reviews and criticism?

Reviews are evaluations of individual films; criticism considers film in general and therefore deals with many films. Reviews are usually aimed at the present, the contemporary marketplace, and are therefore often meant to be forgotten soon after they’re read; criticism should been meaningful for much longer, quite apart from what’s currently playing at cinemas, and therefore is likelier to be used and remembered for a much longer period of time. In these terms, a film review can also turn out to be film criticism if it proves to be remembered and is useful in the future.

What makes you believe, like half of your friends and colleagues, that we are “approaching the end of cinema as an art form and the end of film criticism as a serious activity”? What do you mean by “a serious activity”? Don’t you consider the contributions of your readers as serious?

Sometimes the contributions of readers qualify as criticism and sometimes they don’t; sometimes they’re serious and sometimes they aren’t serious. (What I mean by “serious” usually means something relating to life and the world and something more than light diversion or inconsequential entertainment.) In any case, as a rule I tend to disagree with friends and colleagues who argue that we’re “approaching the end of cinema as an art form and the end of film criticism as a serious activity,” but this is mainly because, unlike them, I don’t necessarily equate cinema with celluloid and analog projection and what’s currently playing at commercial cinemas, and I don’t necessarily equate criticism with what’s published on paper in magazines or books

If, as you also wrote, “we’re enjoying some form of exiting resurgence and renaissance” in film criticism, what makes it different from the other — and older– forms of film criticism?

Thanks to digital forms of cinema, we have a wider choice of what films we can see and discuss and write about, and thanks to the Internet, we have a much wider and more global choice of whom we can communicate with. Also, thanks to video essays, we can sometimes quote more directly from the films we discuss, and therefore discuss them in closer detail, and more accurately. Thanks to links, we can access some texts much more easily than we previously could—although I hasten to add that texts which aren’t available online are now much harder to access than they were before.

When I taught film for a year recently in Richmond, Virginia (2010-2011), I was appalled that most of my students seem to believe that they could learn everything they needed to know without reading. This is complicated, of course, by the fact that in some cases they didn’t regard their own accessing of anything on the Internet (as opposed to books, newspapers, and magazines) as reading. But maybe learning to communicate with misspellings and typos on Twitter is not exactly the same thing as what we used to mean by reading and writing.

If film criticism is ephemeral, what about film criticism on the Internet? Speaking about the journalistic genres, is film criticism on the Internet a new genre or a new format of the same genre?

It can be both; see my answers above. And truthfully, whether anything is ephemeral or not, on the Internet or elsewhere, is largely up to us.

In your opinion, what kind of “mutations” feature criticism on the Internet? Do you think features like interactivity, multimedia or hypertextuality are changing the way critics write about films and also how people read about movies? In which ways?

Yes, interactivity, multimedia and hypertextuality all change the ways critics write about films and the ways that readers read film criticism. The ways this happens are indicated in the words themselves: the reading and writing is more interactive than before, and they use multimedia forms and hyperlinks in ways that didn’t exist previously.

Do you think there are some kinds of forces that cause mutations of this kind? Which ones, in the case of film criticism on the Internet?

The major forces at play are capitalism and sharing—and this includes piracy, which can be a form of capitalism and/or a form of sharing.

Nowadays, everyone who wants to discuss movies can do it on his or her own, on blogs, Facebook, Twitter, etc. In this case, what’s are the differences for a film critic in the 21st century?

More choices in terms of both viewing and reading, at least if you wish to be aware of those choices and are focused about following your own particular interests. Fewer choices in terms of both viewing and reading if you choose to be unadventurous and conform to what most people are doing.

Do you believe that, in the future, a film review can be in the form of a dialogue? Is it possible?

Of course, and this is already happening in the present; the possibilities of email and blogging make it much easier than it used to be. Over the past couple of years, for instance, I’ve been involved in one roundtable discussion about Robert Bresson and in a series of exchanges with another critic, Kent Jones, about Bresson and Jean-Luc Godard. The same concept already exists in DVD and Blu-Ray audio commentaries that take the form of dialogues—the form that I personally prefer in most cases when I’m asked to do them. (So far, I’ve done two audio commentaries with James Naremore about Orson Welles films, one with Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa about Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-up, and one with David Kalat about the longer version of Metropolis.)

Do you know if your books will be published in Portuguese?

Apart from an unauthorized (i.e., pirated) 1999 Brazilian edition of my 1993 book about Eric von Stroheim’s Greed called Ouro e Maldição (unauthorized, that is, by me; the original publisher, the British Film Institute, may have authorized it, but they neither told me about it nor even admitted to its existence when I asked them about it several years ago) and a Brazilian/Portuguese edition of Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich’s This is Orson Welles, which I edited around the same period, I’m unaware of any of my books having been translated into Portuguese, or any plans for this to happen. I hope this situation will change.