From Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 510). — J.R.

Mes Petites Amoureuses

France, 1975

Director: Jean Eustache

Southwest France, circa 1950. Daniel, a schoolboy living with his grandmother, recalls hitting a schoolmate gratuitously, and getting his first erection as a candle-bearer during Mass. Impressed by a sword-swallower in a circus who lies down on broken glass, he duplicates this feat with artifice and fake blood to impress his friends, but later is overcome by a local girl who forces him to the ground and sits on hirn. After he has passed his entrance exams, his mother arrives on a visit with her lover José, a Spanish labourer. Eventually he moves to the city to join his mother and José, but the former forbids him to attend school and has him work without pay as an apprentice to Henri, José’s brother, at a bike repair shop. Spending much of his time looking at women, he goes to see Pandora and the Flying Dutchman at a local cinema where, imitating another boy in the audience, he kisses and caresses a girl seated in front of him, but then leaves the film before it is over. He frequents the local Bar des Quatre Fontaines, where he observes his more amorously active friends, and also attends a local fair where he feels the leg of a girl in the crowd while they listen to the singing of other girls from the nearby convent of St. Marie. He learns that Henri is closing his shop for the summer and that he can visit his grandmother. He is invited by friends on a trip to a dance at St. Marie’s, and he borrows a bike. Arriving at the village that afternoon, he and another boy pick up two girls on the road; wandering into a field with one of them, Françoise, Daniel kisses her but she refuses to have sex with him. Visiting his grandmother somewhat later, he goes out on a walk with his old friends and attempts to make love with the girl who once pinned him to the ground, but she breaks away from him and he joins the others.

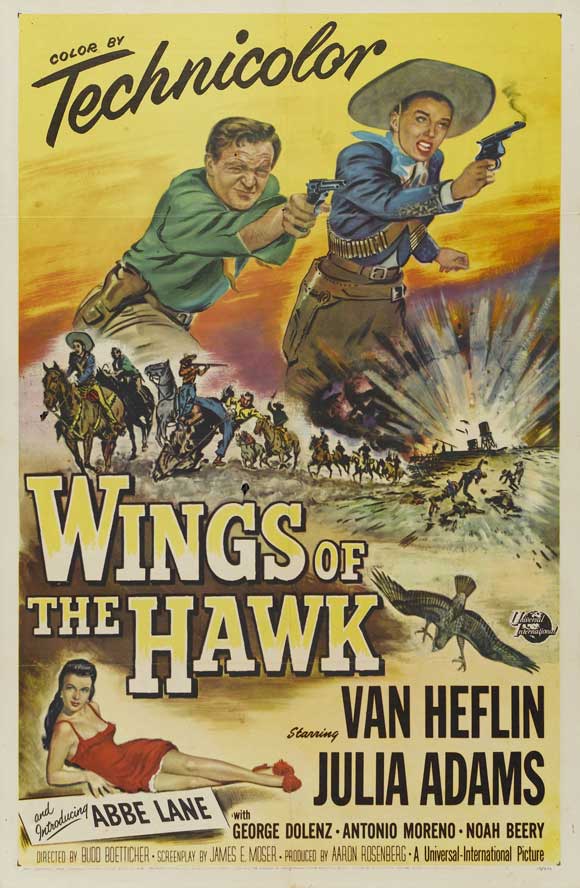

A disappointing follow-up to La Maman et la Putain (1973), Jean Eustache’s latest film of autobiographical recollection reverts to the less rigorous, more episodic form of Le Père Noël a les yeux bleus (1965) while focusing on its hero at a still younger age, on the brink of flustered puberty. Working in a documentary-influenced tradition which he shares with Jacques Rozier and Maurice Pialat (the latter of whom has a small role here) — a strain which can probably be traced back to Renoir’s Une Partie de Campagne, but which has many literary and non-French equivalents, such as Frank Conroy’s Stop-time — Eustache uses a form of ellipsis, an off-screen first-person narration and a deliberate inexpressiveness in his hero’s performance which all seem derived from Bresson. There is also a small quota of carefully selected film references which reek of the Nouvelle Vague and some of its more decadent consequences, like Bogdanovich (not only substantial extracts from a French-dubbed Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, but also comments about Révolte au Mexique. the French title of Budd Boetticher’s Wings of the Hawk). What is regrettably missing from this careful blend is any pronounced urgency or freshness, or a proper sense of distance from the material, of the kind which gave La Maman et la Putain such a powerfully purgative charge. All the tremors of awakening passion and self-definition are recorded with a diligence and sense of social nuance which usually eliminate sentimentality, but still often remain open to charges of self-pity. Admittedly, without the example of Eustache’s previous film these strictures would seem less important: as an overall reconstruction of a time, place and mood, Mes Petites Amoureuses is so conscientious in achieving its modest aims that it might seem unfair to demand more from it. Purely in terms of narrative construction, the oblique and gradual exposition of central facts about the characters is carefully handled, so that, for instance, we only learn that the hero’s name is Daniel when he introduces himself to Françoise near the end, on his first real ‘date’. And the direction of this episode, the longest sustained event in the film, is subtly paced and balanced so that the climactic kiss before the revelation — recorded by a slow, semi-circular Vertigo-like pan round the young couple and accompanied by the chatter of country insects — is effectively prepared for. What ultimately disappoints is the utter familiarity of the material, which Eustache’s control is able to camouflage or minimize in places but not really transform. And what remains perplexing is that, with so many important and fascinating works in the contemporary French cinema still unavailable in this country — by Garrel, Marc’O, Moullet, Pialat, Pollet, Rivette and Rozier, among others — we should be offered such relatively listless and unexciting material in their place.