From The Movie, Chapter 65, 1981.-– J.R.

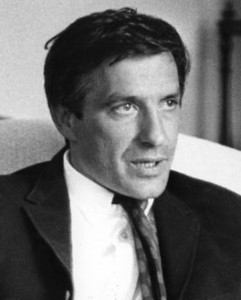

One of the most paradoxical and controversial of all the American independents, John Cassavetes has always placed actors and acting at the center of his film-making conceptions. An actor himself, he has used his craft as a means of financing his own productions — which are themselves celebrations of acting. ‘Directing really is a full-time hobby with me,’ he confessed in an interview in the late Sixties. ‘I consider myself an amateur film-maker and a professional actor.’

Born on December 9th, 1929 in New York City, the son of a Greek immigrant who made and then lost a fortune in business, Cassavetes attended Colgate College as an English major. It was there that his interest in acting was sparked, and he enrolled in the American Academy of Dramatic Arts shortly after graduation.

Delinquent turns director

Following a stage debut in a stock company and a bit part in a Hollywood feature, Fourteen Hours (1951), Cassavetes gradually acquired his reputation as a young actor by appearing in television dramas, where he specialized in juvenile delinquent parts. By the mid-Fifties, budget, he was re-creating one of these roles in a film about a family being held captive by hoodlums, The Night Holds Terror (1955). Juicy parts followed in Crime in the Streets and Edge of the City (both 1956).

Probably the most popular of Cassavetes’ television appearances was as the star of the detective series Johnny Staccato (1959-60). He used his own earnings from that program to support his experimental feature, Shadows (1960), which grew out of an acting workshop that he taught. Shot in 16mm on a miniscule budget, and improvised by a talented cast of unknowns out of sketchy material provided by Cassavetes, the film had an unusual genesis.

The popular Manhattan radio personality lean Shepherd visited the class one night, was mightily impressed by what he saw, and urged Cassavetes to appear on his late-night show, where listeners were asked to send in small donations so that a film could be made. The ploy worked, and the eventually released film created enough of a sensation to secure Cassavetes a Hollywood contract.

Undeniably flawed in many particulars, Shadows had a sensitivity and power in relation to its subject — a closely-knit black family of two brothers and a sister living in Manhattan that came across as a revelation to audiences. The film’s tracing of racism and its effects on an unsuccessful nightclub singer (Hugh Hurd) and his younger siblings — a juvenile delinquent (Ben Carruthers) and adolescent virgin (Lelia Goldoni) — is remarkable for the fact that it remains observable almost exclusively through the nuances of the performers; there is scarcely a reference to the subject of race in the dialogue.

Cassavetes’ directorial stint in Hollywood proved unsatisfactory and frustrating for all parties concerned, although it produced two offbeat features. One was a mawkish yet singularly haunting and memorable saga of small-time jazz musicians, Too Late Blues (1961), made for Paramount, with Bobby Darin and Stella Stevens. The other — A Child is Waiting (1963) — starring Judy Garland and Burt Lancaster, and set in an institution for retarded children, was started for producer Stanley Kramer who had Cassavetes replaced after four months, apparently because of a disagreement over the film’s approach to its subject. (According to Cassavetes, his own thesis, in contrast to Kramer’s, was that retarded children shouldn’t be institutionalized.) Also appearing in this film was the gifted Gena Rowlands, Cassavetes’ wife — a stage actress who has since played the starring role in no less than five of Cassavetes’ seven subsequent movies, all of them independently produced by his own production company.

About Faces

Five long years were to pass, however, before Cassavetes’ distinctively rough-hewn and actor-centered cinema reappeared, dramatically and decisively, in the psychodrama of Faces (1968). By this time, his focus had shifted to a more commercial subject — the American suburban middle-class — which was further explored in his next two features, Husbands (1970) and Minnie and Moskowitz (1971).

Not that Cassavetes had remained idle in the intervening five years. Apart from shooting and editing the 16mm Faces piecemeal over most of this period, he was doing some of his best-known work as a Hollywood actor –- still usually playing heavies — in such films as The Dirty Dozen (1967) and Rosemary’s Baby (1968), which were helping to finance his independent project. (His role in the latter, as an egotistical actor who sells his wife to the devil for procreative purposes in exchange for a good part, may have reflected some of his own tenacity in getting Faces made.) Somewhat earlier, he played in a version of The Killers (1964) — directed by Don Siegel — in which he was clearly out-ranked in villainy by one Ronald Reagan, who was giving his last film performance.

After editing Faces down from a six-hour version to 129 minutes and blowing it up to 35mm, then devoting a lot of time and energy to promotion, Cassavetes went on to enjoy a substantial success with the film. A saga of sexual frustration set in Southern California which involved, among others, an estranged suburban couple (Lynn Carlin and John Marley), a call girl (Rowlands) and a gigolo (Seymour Cassel, a Cassavetes regular), the film obviously hit a raw nerve. Spectators identified closely with the nervous laughter, embarrassment and anguished responses to loneliness of the characters, and the Cassavetes manner — which less sympathetic viewers could describe as giving actors enough space and rope with which to hang themselves — was firmly established.

Husbands, Cassavetes’ flrst independent feature in color and 35mm, is also his only attempt to date to write, direct and play a leading part in one of his films (and the film was produced by his production company). He joined forces with two actor friends, Ben Gazzara and Peter Falk, to depict a trio of drinking companions out on an extended spree to mourn the recent death of a friend. In the ensuing jaunt that takes the men all the way from suburban New York to London and back again, Cassavetes pushed the compulsively macho, carousing side of his style about as far as it could go.

Around the beginning of the Seventies, Cassavetes was preparing one of his most remarkable acting roles in a film written and directed by Elaine May. This was the nightmarish and infernal Mikey and Nicky — a paranoid parable of betrayal between gangster friends, set in Philadelphia during a single night, and a film that, due to diverse complications, wasn’t completed or released until six years later in 1976.

Cassavetes’ next film, Minnie and Moskowitz,was a more relaxed and conventional romantic comedy about a parking-lot attendant (Seymour Cassel) and museum curator (Rowlands). Following this, he returned to whipped-up psycho-drama with a vengeance in A Woman Under the Influence (1974), another big commercial success. Charting the nervous breakdown of a working-class wife and mother (Rowlands, married to Falk) over two and a half hours, the film resumes the almost ‘pointillist’ manner of Faces in which fleeting behavioral tics are liberally applied by the actors on a broad canvas as if they were tiny dabs of paint.

All in the family

In the same film, one can see Cassavetes’ impulse to enlist friends and family reaching some sort of apogee: members of the Cassavetes, Rowlands and Cassel families — including parents and children — are all present in the cast. And it seems worth noting that familial groupings, both real and enacted, are at the center of Cassavetes’ three subsequent features — The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976), Opening Night (1977) and Gloria (1980).

‘I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,’ the sentimental anthem that resounds so significantly throughout the closing moments of The Killing of a Chinese Bookie — might not be too inappropriate an expression of what Cassavetes’ warm, loose and intuitive cinema is all about. It implies a radical commitment to people and their outsized emotions that goes beyond the usual dictates of thought and logic, and a position that necessarily accepts more than it can understand.

Even while Cassavetes continues to play unsympathetic parts in the films of others, as in Brian De Palma’s The Fury (1978), his own productions reveal nothing but unconditional empathy for the varied plights of a soft-hearted nightclub owner (Gazzara in The Killing of a Chinese Bookie), an ageing actress (Rowlands in Opening Night) and a tough broad with little taste for kids (Rowlands again, in Gloria). As we find him coming full circle from his juvenile delinquent acting parts in the Fifties to the violent gangster melodramas of The Killing of a Chinese Bookie and Gloria, what has grown in the process is a sense of character rich, vibrant, and full of life.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM