Here’s the unedited version of a review I wrote for In These Times, published in their September 3, 2008 issue. — J.R.

I can’t quite follow all of the offscreen sound bites preceding the main title of Tia Lessen and Carl Deal’s Trouble the Water. But it’s clear from the media voices I can transcribe that they concisely present this documentary’s agenda — at the same time we see the intertitle “September 14th 2005/Central Louisiana” appear onscreen and then get our first glimpses of some of the people who’ll shortly become this documentary’s central characters, seated around a picnic table.

Two of the offscreen voices come from George W. Bush; the others all sound like they come from newscasters or interviewees:

1. “About 300,000 people displaced by Katrina have been scattered to at least a dozen states.”

2. “Surviving Katrina was one thing; now people are just trying to survive the aftermath.”

3. “[inaudible]…evacuees were rolling in…”

4. “It’s been called the largest migration in the country since the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.”

5. Bush: “I don’t think anybody anticipated the breach of the levees.”

6. “For years officials have warned that the levees could break.”

7. “I don’t believe for one minute that anybody allowed people to suffer because they were African Americans.”

8. “[inaudible]…had the same reaction that they were all white people.”

9. Bush: “We’ve got a job to defend this country in the War on Terror and we got a job to bring aid and comfort to the people of the Gulf Coast, and we’ll do both.”

An apt evocation of The Grapes of Wrath and its own celebration of heroism, survival, and community grows out of #1-#4, especially #4, while the remaining sound-bites all seem devoted to exposing or in two cases countering the lies and/or denials in #5, #7, and #9. It might even be said that the two most important characters in this real-life saga, 24-year-old Kimberly Roberts and her husband Scott, both heroic residents and victims of New Orleans’ Ninth Ward, register at times as updated versions of Ma Joad and Tom Joad —- Jane Darwell and Henry Fonda in the 1940 movie — even though Steinbeck’s duo are mother and son, not wife and husband, and white, not African-American.

One could hypothesize that the key turning point in many Americans’ perception of Bush —- a shift in his image from heroic warrior to inept, hypocritical poseur — was the TV coverage of Hurricane Katrina and its devastating aftermath as well as the wholly inadequate ways it was officially anticipated, making the government’s indifference to large portions of the population both palpable and inescapable. The follow-up perception — that you can’t be a warrior without an actual war (as opposed to a couple of metaphorical ones) — has regrettably been much slower in forming, thanks to a deceitful media vocabulary that remains firmly in place, using “war on terror” to stand for diverse security measures and “war in Iraq” to stand for a military occupation. This makes it easier to postulate in both cases a war that can only be waged permanently–without any clear definition, much less hope, of victory. (This was at least obliquely clarified when the New York Times recently rejected an Op Edit piece by John McCain for its failure to pinpoint what a victory in Iraq might entail.)

But we can at least see the sort of aid and comfort that Bush has in mind when we hear about Naval officers at gunpoint preventing Kimberly, Scott and a crowd of their neighbors from finding even temporary shelter from the flood in a closed but dry naval base ten blocks from their house, with 200 empty family-housing units and over 500 evacuated rooms. “We had to do our job and protect the interests of the government,” one of those officers calmly explains; and if this leaves any doubts about whose government he’s referring to, the commendation that Bush subsequently gave to those officers for “defusing a potentially violent confrontation” should clear that matter up. “If you don’t have money, if you don’t have status, you don’t have a government,” one of Kimberly’s Memphis relatives remarks, after Kimberly laughingly describes having been treated as “un-American, like we lost our citizenship.”

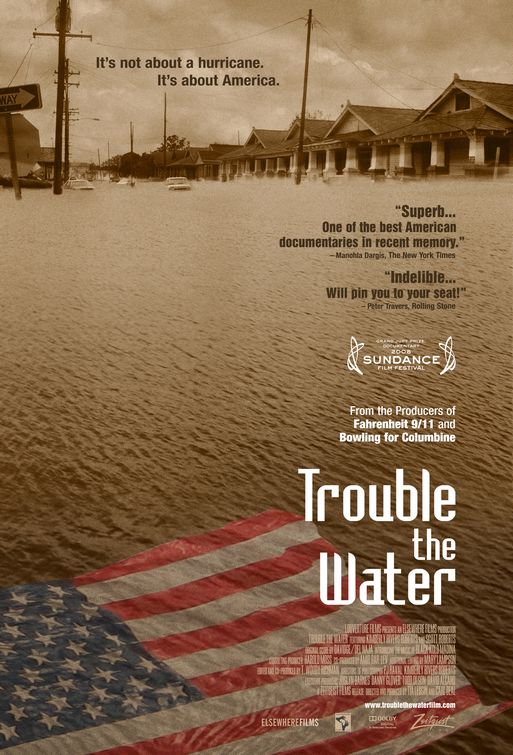

Ironically, it was the National Guard’s public relations team that inadvertently helped to set the agenda for this documentary. Flying to Louisiana a week after Katrina struck, Lessin and Deal —- producers of Fahrenheit 9/11 and veterans of other Michael Moore documentaries — originally wanted to film the return of National Guard troops from Baghdad to New Orleans. But the p.r. people blocked their access, reportedly saying, “Fahrenheit 9/11 screwed it up for all you guys.” Even though some vestiges of their original plan remain in the film, Lessin and Deal luckily met Kimberly Roberts soon afterwards — an aspiring rap artist with the rap alias Black Kold Madina who’d coincidentally bought a cheap video camera shortly before the storm hit and had then documented her own immediate experience of it. So the producers-directors decided to let her story—-her raw footage and their recounting of her further adventures–become their focus.

As storytelling this has certain glitches. The film keeps cutting between Kimberly’s free-wheeling footage (supplemented by various smooth TV news reports) and Lessin and Deal’s footage, which either documents or retraces subsequent events (such as Kimberly and Scott driving a truck full of evacuees to a town in northeast Louisiana, or eventually returning from her cousin’s place in Memphis to their old neighborhood in the Ninth Ward), and some plot details remain fuzzy. Even after two viewings, I’m still not clear about how they acquired the truck.

But as a portrait of the couple and their extended family–including two dogs and a cat as well as various relatives and neighbors — Trouble in Water is wonderful, and what it has to say about whom you can trust in a crisis if you’re poor and black couldn’t be more lucid and direct. Evidently it’s this underlying message that prompted some potential distributors at Sundance to shy away from the film, even after it won the grand jury prize there, with the reported complaint that it was “too black” and didn’t have enough white people in it. But it’s really less the absence of white people in this documentary than their placement in the slicker sections that’s at issue. The single most hilariously shocking bit is a musical commercial for New Orleans tourism made just before Katrina hit, enthusiastically hawked by a young white woman afterwards. While there are certainly a few black musicians in it playing Dixieland, the white dominance of the band and its audience is so glaring that no commentary on it is needed.

It’s also clear that part of what makes Kimberly, Scott, and their friend Brian so positive, generous, and indestructible is their having managed to overcome their drug-related pasts, which they all talk (and, in Kimberly’s case, marvelously rap) about. To their wondrous credit, having survived that particular disaster, they miraculously seem to regard the cataclysmic greenhouse effect, the loss of their worldly possessions and several loved ones, the government’s callous lack of concern and ineffectuality, and the subsequent profiteering of mercenaries (succinctly documented by Naomi Klein in The Shock Doctrine) as lesser setbacks they can somehow triumph over.