From The Soho News (October 29, 1980). — J.R.

Nicholas Ray — supreme Hollywood hero of Godard, Rivette, Rohmer, Truffaut; passionate outlaw and bullshit artist; director of They Live By Night, In a Lonely Place, Johnny Guitar and Rebel Without a Cause – died last summer at the age of 67. But he made two films about his dying before he went. Actually it would be more precise to say he worked on two films about his dying, neither of which is complete, both of which I’ve been able to see this year.

The first of these is We Can’t Go Home Again, an epic 35mm feature made by Ray in collaboration with his wife, Susan, and his film students in the early ’70s. Susan is trying to raise money to complete the film, and I’m hoping that she can find it. When she showed the tattered workprint to me and a few other interested parties on a Steenbeck early last July, pieced together from about 30 percent of the material, it was apparent that this remarkable, impossible, impressive and irritating work in progress is all of a piece — unlike the version that I’d seen at the Cannes Festival in 1973.

At the time I’d written about the film for Sight and Sound within the wider context of an appreciation for (and some ambivalence about) Ray’s work:

“Surfacing in Cannes in the worst of conditions — not quite finished, unsubtitled, shreiking with technical problems of all kinds, and dropped into the lap of an exhausted press fighting to stay awake through ther 15th and final afternon of the festival — Nicholas Ray’s We Can’t Go Home Again may have actually hurried a few critics back to their hiomes; but it probably shook a few heads loose in the process. Clearly it wasn’t the sort of experience anyone was likely to come to terms with, much less assimilate, in such an unfavorable setting, although the demands it makes on an audience would be pretty strenuous under any circumstances.

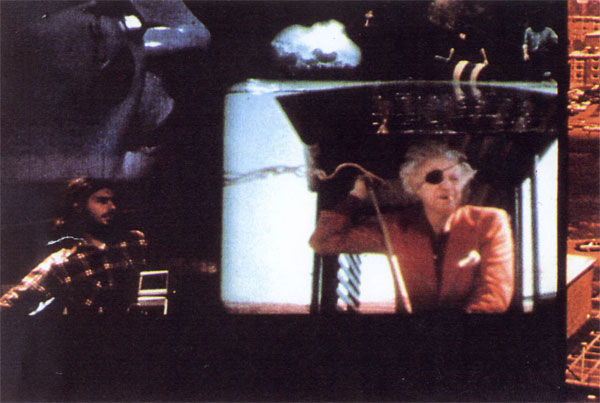

“Created in collaboration with Ray’s film class at the State University of New York at Binghamton, and featuring Ray and his students, the film attempts to do at least five separate things at once: (1) describe the conditions and ramifications of the filmmaking itself, from observations at the editing table to all sorts of peripheral factors (e.g., a female student becoming a part-time prostitute in order to raise money for the film); (2) explore the political alienation experienced by many young Americans in the late ’60s and early ’70s; (3) demystify Ray’s image as a Hollywood director, in relation to both his film class and his audience; (4) implicate the private lives and personalities of Ray and his students in all of the preceding; and (5) integrate these concerns in a radical form that permits an audience to view them in several aspects at once. Thus, for the better part of two hours, six separate images are projected on the screen together, juxtaposing super-8 and 16mm footage against a 35mm backdrop (with the aid of a video synthesizer) in one crowded fresco.”

***

Today, thanks to further work done on the film by Ray in the mid-’70s — editing, labwork, and a narration that he added himself — the film is in a much more coherent and lucid shape. Susan estimates that it needs about nine more months of editing. This means incorporating material that wasn’t available when Ray was doing his last assemblage in 1976, “researching 40 boxes of film and sound to do full justice to the material and to insure technical consistency.”

“It’s funny,” she said to me last June, “there’s a lot of work, and there’s not a lot of work. The film has a life of its own which can’t and won’t be tampered with. It’s a complete statement. It’s just grammatically inexact.”

As before, the film oscillates between the lives, political engagements and problems of the students and Ray’s own problems and ambivalent stances in relation to them and himself. Early on, wearing a red jacket that inevitably recalls James Dean’s in Rebel, he’s shown going into a barn with a rope, bent on hanging himself — a project that he fumbles. (”I made 10 goddam Westerns and I can’t even tie a noose,” he mutters hyperbolically after the noose slips free.)

Soon afterward, dressed as a Santa Claus on a highway, he mutters some more — about needing a drink and “Who the hell ever invented zippers?” — when he’s hit by a speeding car. After a mock funeral performed by his students, he’s discovered back in the hayloft by one of them, Leslie, who listens sympathetically to his woes. (”Have you ever been to a faculty party?”) Richie, who lives with Leslie, invites him to stay at the house they’re sharing with some other students.

The story continues well past graduation and into the Republican convention in Miami in the summer of ‘72, introducing additional students along the way, before Ray is shown attempting suicide again — this time successfully. (Or is it an accident?) His parting message to his students: “I was interrupted….Take care of each other…all the rest is vanity…and let the rest of us swing.”

It’s hard to know how to respond to his parable of self-destruction, filmed almost a full decade after Ray’s last commercial feature, 55 Days at Peking — except to assert without a moment’s hesitation that its formal interest far surpasses that of the Samuel Bronstein spectacular that finished off Ray’s “official” career.

The multiple images that were combined via rear projection photography are often extraordinary, and the total effect of this graphic, innovative, agony-ridden document seems to be somewhere between the Guernica of disaffected America that it clearly aims for and the shattered bathroom mirror in which James Mason examines his fragmented features and identity in Bigger Than Life, his most disturbing Hollywood film. The dialectic between cracked self and atomized other is a central theme throughout, perhaps exprssed most poignantly — and bitterly — in the film’s title, We Can’t Go Home Again, as well as its punning credit signature, “by US”.

***

If We Can’t Go Home Again charts an apocalyptic falling apart, Lightning Over Water constitutes a no less tortured effort at reconstitution, equally (and no less uneasily) poised between fact and fiction. Embarked on jointly by Ray and Wim Wenders (credited as codirectors) last spring, when Ray knew that he was dying of cancer and wanted to work again, it is being re-edited in California, more than five months after being shown at the Cannes Festival.

It was shortly before Cannes that I saw an early version of Lightning Over Water at a private New York screening, presided over by Wenders himself, who afterward asked the gathered audience for reactions. He also asked critics present not to write about the film — a request that I’ve honored until now and am ignoring only because substantially the same film has been seen at Cannes and, more recently, Venice, without any press bans. (Another version — which is said to be composed of 50 percent new material — is close to completion.)

Leaping restlessly back and forth between film and transferred video, and largely shot in the Rays’ Soho loft and Nick’s hospital room, Lightning Over Water features Ray and Wenders as well as their wives, all “playing” themselves. (Wenders is married to the country singer Ronee Blakley, one of the leading performers in Nashville.)

When I asked Susan Ray how much of the film is autobiographical and how much is fictional, she responded, “I don’t see a difference. It may expose the flaws in my perception of reality, but I don’t see a difference between fiction and fact — I see them as alternating strata toward the center of the earth. There were some things in the film that wouldn’t have happened unless we had reorganized them a bit. On the other hand, by their happening, the real tension in the situation came better to light — so you achieved a fact through a fiction.”

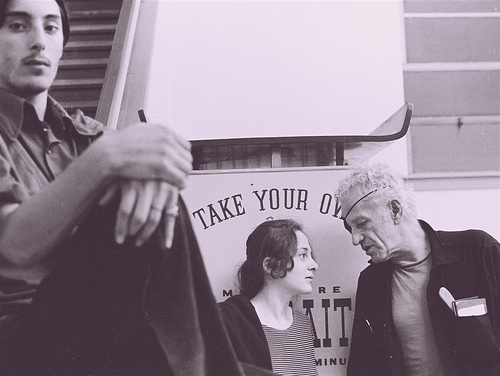

One thing that makes my own relationship to the film a somewhat troubled one is a member of an afternoon of shooting that I was present at in May 1979 (none of which produced usable material). One of the producers, Pierre Cottrell, an old friend, had passed along an invitation to me to come to the Museum of Modern Art one afternoon, when Ray would appear between screenings of a couple of his films to answer questions from the audience. Wenders was in California at the time working on Hammett, his feature for Francis Coppola, but Ray and the crew decided to go on shooting in his absence.

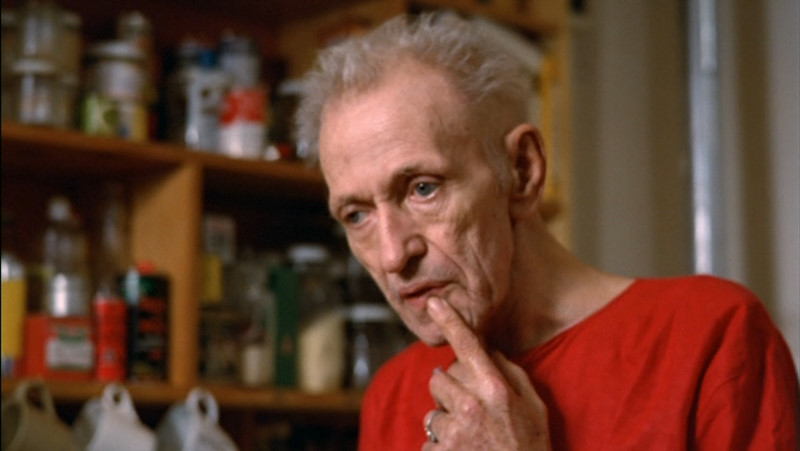

To film this sequence, Ray had to be brought from the hospital in a wheelchair that was hoisted onto the stage of MOMA’s auditorium, I had met him on three previous occasions — had one bought him a drink in Paris and more recently had had dinner with him and a couple of mutual friends in Soho, after he’d joined AA, when he seemed in much better shape. The loss of an eye due to an embolism in early 1970 and years of hard drugs and hard living had already taken their toll. But nothing could have prepared me for the sight of the tiny, emaciated figure chain-smoking on MOMA’s stage, while a dull Sunday afternoon audience asked such questions as would Mr. Ray please care to list the titles of all the films that he’d directed.

Finally I was goaded by Pierre Cottrell into asking a question of my own: “How do you feel about the experience of being in this film?” He replied that it was an interesting question that he preferred to answer in a different context — a mutual opportunity that never offered itself. Yet that afternoon at MOMA I couldn’t shake from my mind the macabre notion that Nick Ray’s skeleton was grinning at all of us, taking a perverse pleasure in how shaken we all were by the sight of him.

When I admitted this feeling to Susan she nodded and said, “That sounds likely. Nick was a provocateur, a master wizard. And he was pretty tired by then — that’s true — and in some ways he was pretty discouraged. But I think in other ways he was perfectly capable of running us all in circles and enjoying himself to the hilt while he did it. It wasn’t always easy but it was never dull, this sneak-magician part of him.”

The parts of Lighting Over Water’s footage that I like especially are those depicting the fierce, unbridled pleasure of Ray as a spectator: watching an old friend, Jerry Bamman, rehearse a scene from an adaptation of Kafka’s “A Report to an Academy” in a theater and looking at We Can’t Go Home Again as it’s projected on a large screen in his loft. Even without Ray’s self-willed mythical status — the sort of impulse that would treat his own dying as an existential aesthetic challenge, a final test to his capacities for mise en scene – the latter comes across as an image of rare monumentality, all the more rare in this period of small movies.

Published on 27 Aug 2011 in Notes, by jrosenbaum

This entry was posted on Saturday, August 27th, 2011 at 12:56 am and is filed under Notes. Follow the comments through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and trackback are closed.