From the October 2010 Sight and Sound. I regret a few errors that crept into this piece as originally published, all of which were my own fault and all of which are corrected here. — J.R.

In the interests of full disclosure, I should mention at the outset that Françoise Romand has been a good friend for over two decades. But I hasten to add that she became a friend because of my immoderate enthusiasm for Mix-Up (1985), her first film — one of the strangest as well as strongest documentaries that I know.

To make matters even more mixed-up, I should also point out that, on the region-free DVD bonus of this hour-long French documentary in English, Françoise, after interviewing herself in French, shows her filming of my talking head in English while I attempt to explain why I find her film so powerful and exciting. What follows represents another try.

Filmed over just twelve days, but recounting a multilayered real-life story that covers nearly half a century, Mix-Up recounts and explores what ensued after two English women, Margaret Wheeler and Blanche Rylatt, respectively upper-middle-class and working-class, gave birth to daughters in November 1936 in a Nottingham nursing home, and the babies were inadvertently switched. The switch came about through a filing error that was only confirmed 21 years later, after Wheeler persisted in pursuing her own queasy suspicions, meanwhile keeping contact with the Rylatts. But by then, of course, Peggy and Valerie had grown up with the wrong mothers, Blanche and Margaret respectively.

To take on everything this entailed, Romand enlisted all the surviving members of both families in her radical experiment, staging comic and highly stylized psychodramas about the diverse emotional histories of this colossal mishap — group psychoanalysis as mise en scène (and as découpage). “To me the cinema is a universal language,” she says in her DVD bonus, “because it starts from the unconscious.” And she somehow makes the whole process fun rather than ponderous, even though the emotional currents and issues about identity and destiny run as deeply and as thickly as they do in Carl Dreyer’s Gertrud (which isn’t exactly a comedy).

Because various stages in this long narrative are made to coexist in the present, the plot and characters ultimately register with the density of a 500-page novel. And the subject is treated so exhaustively that the film’s 63 minutes register like a much longer film.

But at no point does Romand pretend to offer an objective, “balanced” account of what happened (even though her recurring imagery, some of it surrealist and/or allegorical, includes babies being weighed on matching scales), and the viewer is obliged to become no less invested. Margaret, an intellectual, had a lengthy correspondence with George Bernard Shaw about this case (we see the boxes of letters, but Wheeler wouldn’t permit Romand to quote from them). Yet it was clearly Valerie who grew up maimed by feeling unloved, whereas Blanche, whose matching hobby consists of collecting tiny pig figurines and cuttings about pigs, and who proudly poses for us in her bowling hat, seems to have given Peggy a genuine sense of belonging.

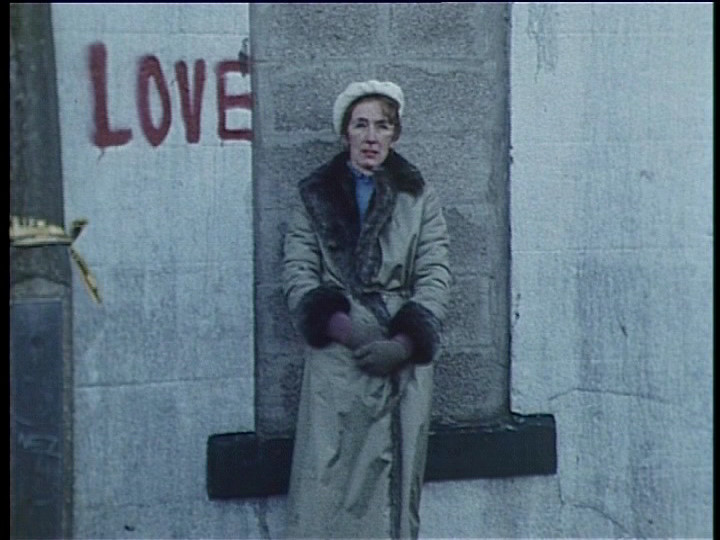

Mix-Up has a French subtitle, Méli-mélo. My dictionary defines that as a “jumble (of facts, etc.); hotchpotch; medley (of people, etc.); clutter (of furniture)” — which helps to define the film’s methodology as well as its subject. Romand’s staging and editing strategies are formal inventions involving many kinds of poetic audiovisual rhymes, involving color, music, sound effects, domestic interiors (with windows, doors, and mirrors predominating as framing devices), and urban exteriors (with various modes of transport — bus, railroad, walking — predominating here). There are also some Godardian juxtapositions of language and image: during walks, Valerie and Peggy each stand in front of key color-coded words, scrawled like graffiti on peeling walls.

The intermingling of fiction and non-fiction produces many daring mixes and clashes. (When Martin, Margaret’s affable youngest son, crouches as an adult under a table to describe a conversation he overheard under the same table at age 13, the moment is uncanny.) Through the ever-widening cast of relatives — mostly composed of siblings, and ranging all the way from Margaret’s droll husband, Charles (the most Dickensian character), to Blanche’s rather dour Jehovah’s Witness son, Peter — a vexing moral question is repeatedly posed: the value of truth and awareness versus ignorance and innocence in living one’s life.

Reseeing Mix-Up recently, and finding it has only expanded and improved over time, I continue to wonder why it isn’t more widely known. Romand’s films, described in her self-interview, are all quite different from one another (and her semi-autobiographical, semi-fictional Thème Je, which she calls The Camera I in English, is even more radical and transgressive than Mix-Up), and this gives her a somewhat elusive profile as an auteur.

But perhaps the most serious obstacle is that her masterpiece poses a genuine challenge in how it makes art and life indistinguishable, merging artistic choices with ethical initiatives, and dares us to do likewise in following her. The implicit rivalry between the two mothers and their respective cultures and approaches to life is everywhere apparent, but part of Romand’s genius is the way she gets the entire family engaged in the serious game-playing of this film’s production, a game we become obliged to play as well. This makes her art both an unpredictable, risky adventure and an unusual form of healing, for the people on-screen as well as for us. The film’s hopeful closing motto, “We all belong together,” may sound a trifle optimistic, but the film itself is nothing less than a multifaceted demonstration of this thesis.

Published on 11 Sep 2011 in Notes, by jrosenbaum