This started out as an essay commissioned by Criterion for their 2011 DVD release and submitted to them in February. They weren’t happy with the result, so we agreed to disagree. — J.R.

When all the archetypes burst in shamelessly, we reach Homeric depths. Two clichés make us laugh. A hundred clichés move us. For we sense dimly that the clichés are talking among themselves, and celebrating a reunion. – Umberto Eco on Casablanca

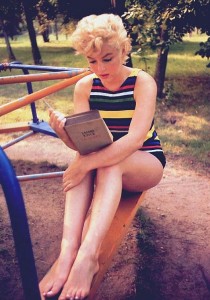

My nightmare is the H Bomb. What’s yours? – Marilyn Monroe’s notes for her responses to a 1962 interview, first published in 2010

As I wrote in my capsule review of Insignificance for the Chicago Reader,

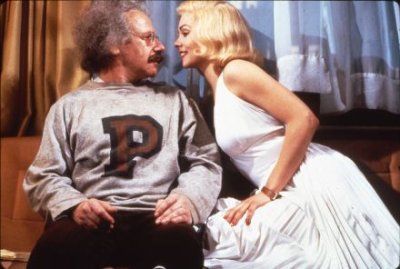

Nicolas Roeg’s 1985 film adaptation of Terry Johnson’s fanciful, satirical play — about Marilyn Monroe (Theresa Russell), Albert Einstein (Michael Emil), Joe DiMaggio (Gary Busey), and Senator Joseph McCarthy (Tony Curtis) converging in New York City in 1954 — has many detractors, but approached with the proper spirit, you may find it delightful and thought-provoking. The lead actors are all wonderful, but the key to the conceit involves not what the characters were actually like but their clichéd media images, which the film essentially honors and builds upon. The Monroe-Einstein connection isn’t completely contrived. Monroe once expressed a sexual interest in him to Shelley Winters, and a signed photograph of Einstein was among her possessions when she died. But the film is less interested in literal history than in the various fantasies that these figures stimulate in our minds, and Roeg’s scattershot technique mixes the various elements into a very volatile cocktail — sexy, outrageous, and compulsively watchable. It’s a very English view of pop Americana, but an endearing one.

The two small bits of information about Monroe and Einstein that are cited above can be found in the first volume of Winters’ entertainingly gossipy autobiography, Shelley, Also Known as Shirley (1980). Combine them with (a) some vague assertions in a conference lecture about some correspondence between the actress and scientist that remains perpetually out of reach and (b) an ingenious and popular optical illusion that manages to merge black and white photographs of the two, both readily available on the Internet, and, given the irresistible allure of postmodernist reverie, these tidbits encourage many bloggers to assert with confidence that an affair between Einstein and Monroe is now an established fact.

There’s surely even less factual basis to the notion that McCarthy found himself impotent with a hooker in a midtown Manhattan hotel room when Johnson’s play is said to be taking place, or that DiMaggio, on the same evening, recited all 13 of the baseball card series that he was in. Or that Monroe illustrated the Theory of Relativity to the scientist with the aid of some toy props, turning it into a piece of performance art. But it’s fantasies of this kind that provide two playful Brits, playwright and screenwriter Terry Johnson and director Nicolas Roeg, with their starting points. For the former this yields what he has called “nuclear consciousness,” even more pronounced in the film than it was in the play; for the latter, it’s partly an occasion for characteristically fragmented Roegian crosscutting — a sort of update of Intolerance featuring pop 50s icons. For both artists, it’s part of the wave of stage adaptations on film that came out in the 80s, along with Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, Betrayal, Streamers, Secret Honor, Fool for Love, Cries of the Heart, and ‘night, Mother, among others.

Johnson’s play originally featured Howard Hughes instead of McCarthy, but Johnson changed his mind halfway through the first draft, after what Rob Ritchie, his literary manager at the Royal Court Theatre, described as “an impromptu visit to the Theatre Upstairs to see what Sam Shepard’s Seduced was about. It was about Howard Hughes – exit Terry Johnson in a cold sweat — it’s a long stagger down from the Theatre Upstairs. Exit Howard Hughes to make way for Senator Joe McCarthy.”

According to Wikipedia’s DiMaggio entry, it was on September 14, 1954 that Monroe was filmed in front of the Trans-Lux Theater on Lexington Avenue and 52nd Street, where her dress was supposed to be billowed up by a gust of wind from a subway grate -– an incident shown in the film Insignificance, but not in the play, precipitating (reportedly in life, but in neither the film nor the play) a loud argument afterwards with her husband, Joe DiMaggio, in the theater lobby. According to Wikipedia’s entry for The Seven Year Itch, this sequence then had to be reshot on a Hollywood soundstage, and the latter footage “is what made its way into the final film, as the original on-location footage’s sound had been rendered useless by the over excited crowd present during filming whistling over Monroe’s see-through panties.” The play is set in 1953; the film updates this to 1954, but by placing the action in March (according to a calendar seen in a bar), this is still half a year prior to the date when Monroe actually had her skirt blown up in front of the Trans-Lux.

For that matter, insofar as Insignificance hovers around the notion that Einstein had something to do with the development of the Atomic and Hydrogen bombs, it’s worth noting some supplementary information that has come to light more recently. Two decades after Johnson’s play opened in London, Fred Jerome, who sued the U.S. government to access a relatively uncensored version of Einstein’s FBI file, wrote that the Army in 1940, apparently in response to a report from J. Edgar Hoover that threw doubt on the great man’s politics and his loyalty, declined to give him security clearance to work on the Manhattan Project.

How much do facts of this kind matter? Quite a bit if “real” history is at stake and hardly at all if it’s a matter of mythology. And it’s typical of our postmodernist confusions that we often can’t distinguish very well between the two.

A game and a provocation built around this dilemma, Insignificance implicitly dares us to sort out the differences between fact and fantasy by playing riffs with the images we already have of DiMaggio, Einstein, McCarthy, and Monroe. Thus paranoia, apocalyptic visions, and cartoon-like notions of sex are invited to intermingle and merge — as critic Raymond Durgnat once described this blend, in relation to the 1955 film Kiss Me Deadly, “the apotheosis of va-va-voom,” and what Eco has described as a conversation between clichés.

Insignificance pointedly doesn’t sort out the differences between fact and fancy; it’s more interested in playfully turning all four of its celebrities into metaphysicians of one kind or another. My favorite illustration of this is when the Actress — offering a sexual bribe to the Senator, who thinks she looks like Marilyn Monroe — existentially concludes, “What the hell — it’s her you want, not me,” thus summing up our own ambiguous and contradictory relation to her character.

All this sport, to be sure, has specifically English inflections. These crazed American icons are being viewed from an amused and bemused distance, and much of the talk qualifies as fancy mimicry. Even some of the measured and formal civility that periodically shines through the banter between the Professor and the Actress might be said to emanate from an English drawing room more than a suite at the Roosevelt:

Actress … If we stand on the tracks a little longer you know what happens?

Professor We get run over? (Pause.) I stay behind afterwards and clean the blackboard.

Actress I don’t like to be patronized.

Professor I’m sorry.

Actress Your apology’s accepted…

Johnson is presumably enough of a researcher to know that McCarthy helped to hound Paul Robeson out of the U.S. But if he also knows that Einstein was an important ally of Robeson a few years earlier, he and his Einstein character aren’t letting on. Clearly they have other fish to fry. And they’re no less mute about the fact that twice in 1953, in June and December, Einstein urged witnesses called before McCarthy’s Committee, the HUAC, and similar “inquisitions” (as he called them) not to testify — a fact reported both times on the front page of the New York Times, but not in Johnson’s bittersweet comedy.

Furthermore, “I didn’t write Insignificance because I was interested in Marilyn Monroe,” Johnson avowed in a 1985 interview with Richard Combs for the Monthly Film Bulletin (August 1985). This film occasioned an extensive rewrite and expansion of the original by Johnson, but even then he couldn’t be sure whether or not he’d ever seen The Seven Year Itch. He also admitted that his “interest in film, which is now quite strong, came out of the experience of adapting the play for Roeg….The whole structure and nature of a play is to do with objects and people and movement. Whereas, in a film, you just cut and get to the next good bit. Plays are essentially about space, where films are essentially about time — to be a pundit.”

One perk of his lack of interest in Monroe is complicating and confounding the popular notion of her as a dumb blonde — a stereotype that she’d helped to create herself — in order to shape and justify his outlandish plot. And as we know now from a recent collection of Monroe’s writing (Fragments: Poems, Intimate Notes, Letters by Marilyn Monroe, edited by Stanley Buchthal and Bernard Comment, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010), she was a curious mixture – an atrocious speller who was completely self-taught, but also someone who was reading Proust’s Swann’s Way on the set of Love Nest in 1951, and can be seen reading the end of Joyce’s Ulysees on the back jacket of Fragments. As the editors of Fragments note, Proust, another faulty speller, once wrote, “Each spelling mistake is the expression of a desire,” and indeed, an important part of the achievement of Johnson, Roeg, and the four lead actors of Insignificance is to see how they manage to collaborate in expressing, repressing, denying, or discovering their characters’ desires as well as their fears, in each case typifying the 50s zeitgeist.

The play stays glued over its two acts to Einstein’s hotel room. The film adds crosscutting and incidental characters, including Monroe’s driver (Patrick Kilpatrick), a hooker with a blond wig who comes to McCarthy’s room (Desirée Erasmus), and, elaborating on a speech by Einstein that was already in the play, a Cherokee elevator man (Will Sampson) who adds another metaphysician to the cast of characters. The new locations include not only the Trans-Lux, but also a bar where McCarthy and DiMaggio nurse their separate grudges, and the shop where Monroe buys her demonstration toys. Perhaps the most significant additions are the brief, telegraphic, and sometimes cryptic flashbacks pertaining to the respective youths of Monroe, Einstein, and DiMaggio, and last but not least, the Elephant in the Room, the H-Bomb itself — which one might say puts in a crucial, last-minute appearance as the celebrity to end all celebrities, dwarfing and making irrelevant all of the others.