Two particular (and very different) moments that I described for Chris Fujiwara’s Defining Moments in Movies (2007). — J.R.

1987 / Full Metal Jacket –- The closeup of a dying Vietcong woman, a sniper.

U.S. (Warner Bros. Pictures). Director: Stanley Kubrick.

Cast: Matthew Modine, Ngoc Le.

Why It’s Key: It condenses the film’s power into an intense, mysterious moment.

I had the rare privilege of seeing Stanley Kubrick’s last war picture — an adaptation of Gustav Hasford novel’s The Short Timers, about his experiences during the war in Vietnam — with war specialist Samuel Fuller, shortly after the film came out. He didn’t much care for the picture, he said afterwards, because he didn’t much like films about training, and besides, this movie wasn’t antiwar enough for his taste; he thought it might even encourage some teenage boys to enlist in future wars. Of course, Fuller had extensive war experience and Kubrick had none, which might have also played some role in forming his bias.

But one thing in the film that he loved without qualification was the close-up of the wounded Vietcong sniper at the end while she’s begging for Joker (Matthew Modine) to finish her off —- above all, for the look of absolute hatred in her eyes. “How did Kubrick do that?” he said with admiration.

It’s a powerful scene in many ways. For one thing, it’s a moment when the Feminine Other that’s been haunting all the grunts throughout the picture is finally confronted head-on —- an obsession that comes to the fore repeatedly in the opening sequence in training camp. It also creates a truly upsetting rhyme effect with the closeup of the insanely grinning “Gomer Pyle” just before he shoots Sgt. Hartman at the end of that opening sequence — a rhyme conveyed almost subliminally through a hum on the soundtrack over both close-ups.

***

1995 / The Neon Bible – “It didn’t snow that year.”

U.K. (Academy/Channel Four). Director: Terence Davies.

Cast: Drake Bell, Jacob Tierney, Gena Rowlands.

Why It’s Key: It reveals the power of imagination in a flash.

Few moments in movies reveal the power of imagination more succinctly than the opening of Terence Davies’ CinemaScope adaptation of John Kennedy Toole’s first novel, written when the southern author was only 16. It opens with 15-year-old David (Jacob Tierney) alone on a train at night, the camera moving past him to the darkness glimpsed outside. Then David at ten (Drake Bell) is seen peering out a rain-streaked window in his rural home to the strains of “Perfidia”, circa 1948, while narrating offscreen, “People came to see us that Christmas. They were nas, those people —- they brought me things…”

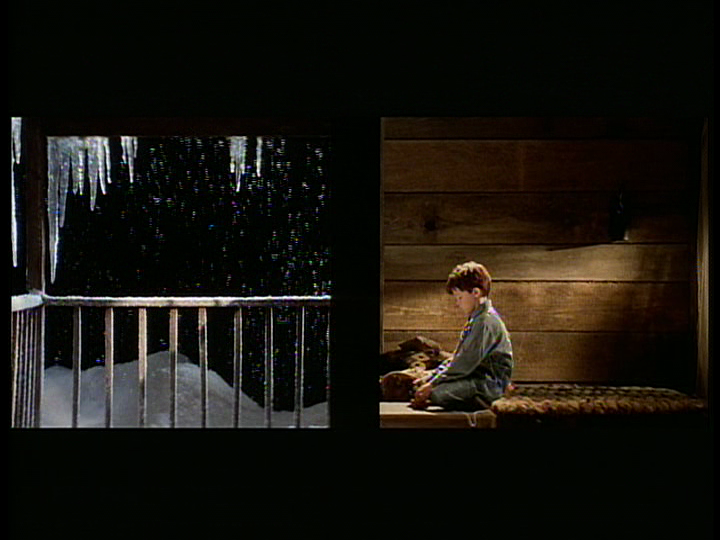

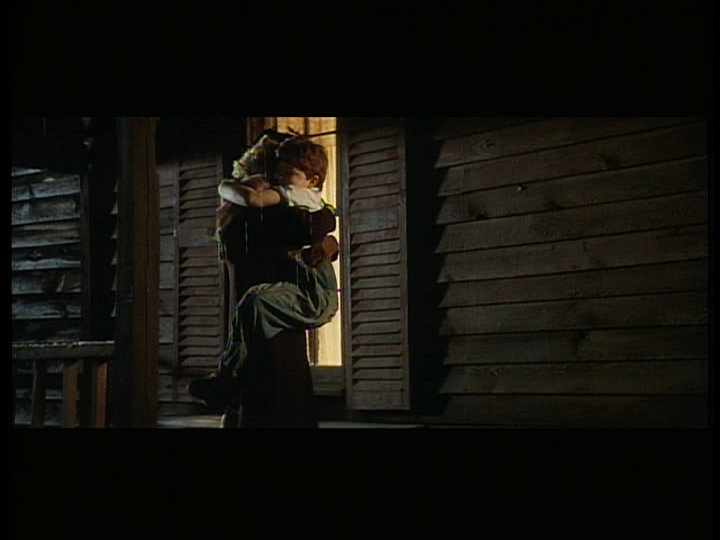

A moment later, we cut to a diptych: on screen left, an empty porch topped by icicles framing an enchanted snowfall, as decorous as a neatly filled box by the surrealist artist Joseph Cornell. On screen right, young David is seated on the floor inside, now looking out the same window in profile, while narrating offscreen, “There was no snow —- no, not that year.” When the next shot shows us his aunt (Gena Rowlands) in full frame greeting him through the window, the icicles are still lining the top of the frame. But a shot later, when David comes out on the porch to greet her, it’s raining again.

Davies, who once compared filling a CinemaScope frame to settling down in Canada, also knows the period like the back of his hand. And the power of snow to briefly supplant rain in a ten-year-old’s mind, as he recollects it all years later, has the force of an epiphany.