From the August 24, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader. This is another film (see capsule review of Rita, Sue and Bob Too, posted earlier today) released on Blu-Ray by Twilight Time. For the record, I much prefer most or all of the features David Lynch has made since Wild at Heart, especially Inland Empire. — J.R.

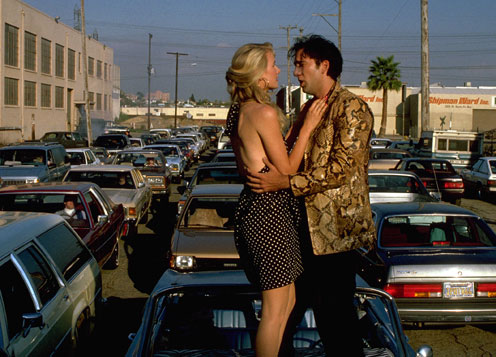

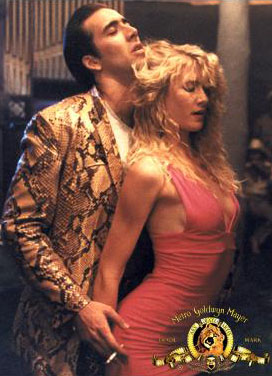

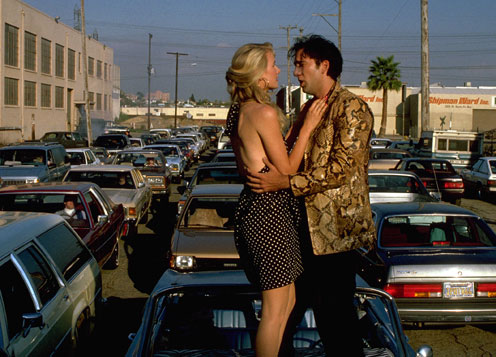

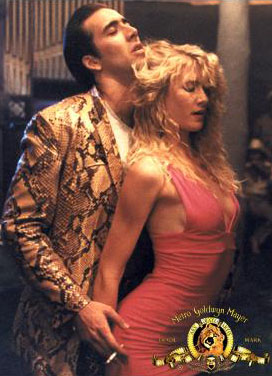

WILD AT HEART

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by David Lynch

With Nicolas Cage, Laura Dern, Diane Ladd, Willem Dafoe, Isabella Rossellini, Harry Dean Stanton, and Crispin Glover.

The progressive coarsening of David Lynch’s talent over the 13 years since Eraserhead, combined with his equally steady rise in popularity, says a lot about the relationship of certain artists with their audiences. A painter-turned-filmmaker, Lynch started out with a highly developed sense of mood, texture, rhythm, and composition; a dark and rather private sense of humor; and a curious combination of awe, fear, fascination, and disgust in relation to sex, violence, industrial decay, and urban entrapment. He also appeared to have practically no storytelling ability at all, and in the case of Eraserhead, this deficiency was actually more of a boon than a handicap. Like certain experimental films, the movie simply took you somewhere and invited you to discover it for yourself. Read more

The following essay was both commissioned and written in early June 2009. My thanks to the Chinese translator Zhanxiong Xu for giving me permission to publish the original English version here.

I’m also pleased to announce that a Chinese translation and edition of one of my own books, Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See, came out in China. I strongly suspect that the subsequent influx of Chinese visitors to this site must have had something to do with its publication. — J.R.

Introduction to the Chinese Edition of More Than Night: Film Noir in its Contexts

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

I

“The Chinese don’t accord much importance to things of the past,” Maggie Cheung maintained in an interview with a French magazine roughly a decade ago (1), “whether it’s films, heritage, or even clothes or furniture. In Asia nothing is preserved, turning towards the past is regarded as stupid, aberrant.”

Interestingly, this statement helps to explain why so many of the most important Chinese films, at least for me, are concerned with the discovery of history, and represent various attempts to reclaim a lost past. I’ll restrict myself to a short list of a dozen favorite Chinese features, all of which exhibit these traits: Fei Mu’s Xiao cheng zhi chun (Spring in a Small Town, 1948); Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Bei qing cheng shi (City of Sadness, 1989) and Xi meng ren sheng (The Puppetmaster, 1993); Wong Kar-wai’s A Fei zheng chuan (Days of Being Wild, 1990) and Fa yeung nin wa (In the Mood for Love, 2000); Edward Yang’s Gu ling jie shao nian sha ren shi jian (A Brighter Summer Day, 1991); Stanley Kwan’s Ruan Lingyu (1992); Tian Zhuangzhuang’s Lan feng zheng (The Blue Kite, 1993); Li Shaohong’s Hong fen (Blush, 1994); and Jia Zhangke’s Zhantai (Platform, 2000), Sanxia Haoren (Still Life, 2006), and Er shi si cheng ji (24 City, 2008). Read more

This article and interview was originally published in the May-June 1973 issue of Film Comment, roughly half a year after the interview took place. I went to work for Tati as a script consultant several weeks after I had the interview, but well before it appeared in print. A few years ago, this piece was reprinted online in the Southern arts magazine Drain. —J.R.

Tati’s Democracy

An Interview and Introduction

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Like all of the very great comics, before making us laugh, Tati creates a universe. A world arranges itself around his character, crystallizes like a supersaturated solution around a grain of salt. Certainly the character created by Tati is funny, but almost accessorily, and in any case always relative to the universe. He can be personally absent from the most comical gags, for M. Hulot is only the metaphysical incarnation of a disorder that is perpetuated long after his passing.

It is regrettable that André Bazin’s seminal essay on Jacques Tati (“M. Hulot et le temps,” 1953, in Qu’est-ce que Ie cinéma? Read more