My book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver: Arden Press), intended by its editor-publisher to launch an annual series, regrettably lasted for only one other volume, by David Ehrenstein, after two other commissioned authors failed to submit completed manuscripts. Miraculously, however, this book remained in print for roughly 35 years, and now that it’s finally reached the end of that run (although some copies can still be found online), I’ve decided to reproduce more of its contents on this site, along with links and (when available) illustrations. I’m beginning with the book’s end, an Appendix subtitled “22 More Filmmakers,” which I’m posting here in three installments, along with links and (when available) illustrations. — J.R.

PAULA GLADSTONE. In Gladstone’s mainly black-and-white, hour-long, Super-8 The Dancing Soul of the Walking People (1978), possession and. dispossession both happily become very much beside the point. Shot over a two-year period, 1974-1976, each time the filmmaker went home to Coney Island (“I’d take my camera out and walk from one end of the land to the other,” she reports in Camera Obscura [No. 6]; “I’d talk to people on the streets and film them”), The Dancing Soul of the Walking People is basically concerned with the space underneath a boardwalk, a little bit like the luminous insides of a translucent zebra on a sunny day — an interesting kind of space, at once public and private, that is traversed by receding strips of light, camera pans, and people, in fairly continuous processions and/or rhythmic patterns. Read more

My book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver: Arden Press), intended by its editor-publisher to launch an annual series, regrettably lasted for only one other volume, by David Ehrenstein, after two other commissioned authors failed to submit completed manuscripts. Miraculously, however, this book remained in print for roughly 35 years, and now that it’s finally reached the end of that run (although some copies can still be found online), I’ve decided to reproduce more of its contents on this site, along with links and (when available) illustrations. I’ll begin with the book’s end, an Appendix subtitled “22 More Filmmakers,” which I’ll post here in three installments, along with links and (when available) illustrations. — J.R.

APPENDIX: 22 MORE FILMMAKERS

All sorts of determinations have led to the choices of the individual subjects of the 18 previous sections — some of which are rational and thus can be rationalized, and some of which are irrational and thus can’t be. To say that I could have just as easily picked 18 other filmmakers would be accurate only if I had equal access to the films of every candidate. Yet some of the arbitrariness of the final selection — particularly in relation to the vicissitudes of American distribution and other kinds of information flow — has to be recognized. Read more

This appeared in The Soho News (August 18, 1981). Apologies for the stupid headline; my editor at the time was addicted to bad puns of this kind.– J.R.

An Enemy of the People

Directed by George Schaefer

Public Theater

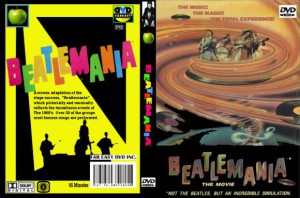

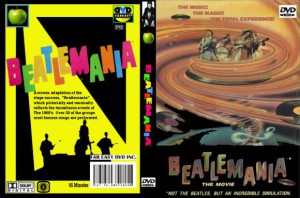

Beatlemania — The Movie

Directed by Joe Manduke

A cherished personal project of Steve McQueen, who served as executive producer as well as lead actor, Henrik lbsen’s An Enemy of the People, scripted by Alexander Jacobs, is a lot more appealing and less forbidding than its cultural aura might suggest. That McQueen was unable to get this 1977 film released prior to his death is unfortunate yet unsurprising; given the absence of outlets for movies of this kind in the United States, I would have thought that cable might prove to be its ideal resting place. But at least for us Manhattan country folk, it’s once again thanks to the underappreciated services of the Public Theater that we’re able to see it at all.

McQueen made this movie when he knew that he was dying of cancer and decided that he wanted to be remembered for something more than his blue-eyed beefcake parts. An advocate of Laetrile cancer therapy -– banned by the FDA, and usually pegged as “controversial” in this country – McQueen had to go to a Mexican clinic to get the treatment he wanted and must have had plenty of reasons to identify with Ibsen’s persecuted, innocent, and idealistic hero. Read more