From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 493). — J.R.

Umarete wa Mita Keredo (l Was Born, But . . .)

Japan, 1932 Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Yoshi moves with his wife and two sons, Ryoichi and Keiji, from

Azabu to a Tokyo suburb, close to the home of the director of the

company where he works. His sons are ostracized and persecuted

by the other boys in the neighborhood; arriving late for school

after Yoshi urges them to get high marks, they decide to play

hooky and do their lessons in a nearby field, forging high marks on

their papers which they bring home to show their father. But Yoshi

is informed by Ryoichi’s teacher that they were absent from school,

and makes sure that they attend the following day. After a delivery

boy whom they befriend overpowers a bully who previously

defeated Keiji, the boys are accepted as leaders by their local

schoolmates. Yoshi’s boss screens home movies for his family

and friends, including his son Taro, Yoshi, Ryoichi and Keiji;

the latter two are horrified when they see Yoshi making faces and

otherwise demeaning himself in the films to please his boss, and a

family fight ensues after they and their father return home. Read more

Written for the catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato in June 2018. — J.R.

A subtle, complex follow-up to Alfred Hitchcock’s biggest hit, Psycho, his 50th feature (1963) is quite different — and not just because this apocalyptic fantasy is his most abstract film, as Dave Kehr has noted, but also because his shift from black and white to widescreen color works in tandem with the abstraction. The same abstraction extends to cosmic long shots worthy of Abbas Kiarostami that seem posed more as philosophical questions than as rhetorical answers. And as soon as we notice that the flippant heroine, Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren), has been color-coordinated, thanks to her blond hair and green dress, with the two lovebirds in their cage that she’s bringing to Bodega Bay as part of an elaborately flirtatious grudge match waged against a disapproving stranger, Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor), it’s already clear that Hitchcock has something metaphysical as well as physical in mind.

What keeps his scare show so unnervingly unpredictable is that the explanation we crave for why birds have started to attack humanity is never forthcoming. (Hitchcock said in interviews that The Birds was about “complacency,” without spelling out whether he meant that of his characters, his audience, or both.) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 5, 1990). — J.R.

As a moviegoer who was privileged to see a good many films, both new and old, in a number of contexts, places, and formats in 1989, I can’t say it was a bad year for me at all. I saw two incontestably great films at the Rotterdam film festival (Jacques Rivette’s Out 1: Noli me tangere and Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan’s A Story of the Wind), and several uncommonly good ones both there and at the festivals in Berlin, Toronto, and Chicago. (Istvan Darday and Gyorgyu Szalai’s The Documentator and Jane Campion’s Sweetie — the latter due to be released in the U.S. early this year–are particular standouts.) Thanks to the increasing availability of older films on video, I was able to catch up with certain major works that I’d missed and see many others that I already cherished.

But considering only the movies that played theatrically for the first time in Chicago, I have to admit that it was a discouraging year. In fact, 1989 was the worst year for movies that I can remember, particularly when it comes to U.S. releases. Gifted filmmakers are granted less and less freedom as the Hollywood studios are taken over by conglomerates and European films are set up as international coproductions — both trends that have been in process for some time now; and the grim consequences of these changes become much more apparent when one takes a long backward look rather than when one considers the immediate surface effects of movies on a week-by-week basis. Read more

Written in July 2008 for an issue of Stop Smiling devoted to Washington, D.C. 2022: In a way, the recent Arrival might be said to qualify as a mystical remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still, and I found it every bit as gripping. — J.R.

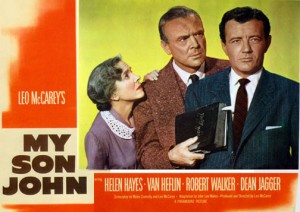

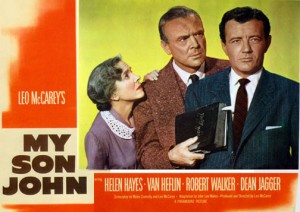

To get the full measure of what Cold War paranoia was doing

to the American soul, two of the best Hollywood A-pictures

of the early 50s, each of which pivots around its Washington,

D.C. locations – The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and My

Son John (1952) — still speak volumes about their shared zeitgeist,

even though they couldn’t be further apart politically.

An archetypal liberal parable in the form of a science fiction

thriller and an archetypal right-wing family tragedy (with deft

slapstick interludes) that’s even scarier, they’re hardly equal in

terms of their reputations. Leo McCarey’s My Son John, widely

regarded today as an embarrassment for its more hysterical elements,

has scandalously never come out on video or DVD [2014 footnote, it’s

now available from Olive Films], though in its own era it garnered

even more prestige than Robert Wise’s SF thriller, having received

an Academy Award nomination for best screenplay. Read more

From Cahiers du Cinéma #334/355, avril 1982 (a special issue called “Made in USA”). I wrote this commissioned article (about two of Robert Altman’s stage productions) in English, while working with Serge Daney in New York on a number of other assignments. The French text is all I have now, and I’ve decided to reproduce it here because it’s the only account of these productions that I know about that are written from a filmic perspective, and the recent release on an Olive Films Blu-Ray of Come Back to 5 & Dime Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (the Altman film, which for me removes most of the major virtues of the Broadway production) makes this perspective all the more relevant….Reproducing this French text has entailed a lot of retyping, and I hope I haven’t made too many mistakes. (I’ve also corrected a few typos, including “Atlman” for “Altman”.) -– J.R.

Après avoir vendu sa maison de production, Lion’s Gate Films, l’année dernière, Robert Altman a annoncé qu’il avait l’intention de se lancer dans une carrière théâtrale, il a d’abord mis en scène à Los Angeles deux petites pièces expérimentales en un acte écrites par Frank South; dans I’une, il n’y a que deux personnages (chacun tenant séparément un monologue et n’échangeant aucun dialogue) ; l’autre n’a qu’un personnage (qui fait un monologue tenant du tour de force). Read more

While less impressive than Souleymane Cisse’s subsequent Brightness, this 1982 feature about campus rebellion and ancestral, tribal memories in contemporary Africa is full of fascination. Bah, the grandson of a traditional chieftain, and Batrou, the daughter of a military governor representing the new power elite, become involved with a campus rebellion, drugs, and each other)which leads to their arrests. Although the social forces of contemporary Mali contrive to keep them and their traditions apart, a recurring dream sequence illustrated by a little boy filling a gourd with water, which symbolizes sharing and the exchange of knowledge, points to deeper links that unite generations as well as this couple. (JR) Read more

Chris Marker’s 1982 masterpiece, whose title translates as Sunless, is one of the key nonfiction films of our time–a personal and philosophical documentary that concentrates mainly on contemporary Tokyo, but also includes footage shot in Iceland, Guinea-Bissau, and San Francisco (where the filmmaker tracks down all of the original locations in Hitchcock’s Vertigo). Difficult to describe and almost impossible to summarize, this poetic journal of a major French filmmaker (La jetee, Le joli mai) radiates in all directions, exploring and reflecting upon many decades of experience all over the world. While Marker’s brilliance as a thinker and filmmaker has largely (and unfairly) been eclipsed by Godard’s, there is conceivably no film in the entire Godard canon that has as much to say about the present state of the world, and the wit and beauty of Marker’s highly original form of discourse leave a profound aftertaste. A film about subjectivity, death, photography, social custom, and consciousness itself, Sans soleil registers like a multidimensional poem found in a time capsule. (Film Center, Art Institute, Columbus Drive at Jackson, Sunday, February 7, 6:00 and 8:00, 443-3737) Read more

Paul Newman stars in this 1982 courtroom drama, playing an alcoholic Boston lawyer who manages to clean up his act enough to represent the victims in a malpractice suit against a Catholic hospital. Sidney Lumet’s direction, like David Mamet’s patchy script (which adapts a Barry Reed novel), may not be quite good enough to justify the Rembrandt-like cinematography of Edward Pisoni and the brooding mood of self-importance, but it’s good direction nonetheless; and there are plenty of supporting performancesby James Mason, Jack Warden, Milo O’Shea, Charlotte Rampling, and Lindsay Crouse, among othersto keep one distracted from Newman’s dogged Oscar-pandering. R, 129 min. (JR) Read more

The first genuine hit in Alain Resnais’ career (1981) takes off from the behaviorist theories of French scientist Henri Laborit, which are illustrated by the stories of three separate characters (Gerard Depardieu, Roger Pierre, and Nicole Garcia), each of whom identifies with a different French movie star and whose lives occasionally cross. While the quasi-determinist theories of Laborit (who occasionally appears on-screen to lecture us in a white lab coat) are never very interesting or persuasive, the film can never really be reduced to them. What matters here is the fluidity of Resnais and screenwriter Jean Gruault’s masterful storytelling; they manage to convey a dense, multilayered narrative with remarkable ease and simplicity. The film is also memorable for its dead-on portrayal of French yuppiedom in its early ascendancy and for its beautifully ambiguous and open-ended finale. 123 min. (JR) Read more

Virginia Woolf meets the German camp underground in this 126-minute extravaganza of performance art and oddity by Ulrike Ottinger. Actually, the political focus is closer to that of Tod Browning’s Freaks than to Woolf’s Orlando, though Ottinger has taken from Woolf the notion of an ideal protagonist [who] represents all the social possibilitiesman and womanwhich we normally do not have. The five episodes situate the hero/heroine in the Freak City department store (along with her seven dwarf shoemakers), in the Middle Ages, toward the end of the Spanish Inquisition, in a circus (where he falls in love with Delphine Seyrig, one of a pair of Siamese twins), and on a grand European tour with four bunnies (during which she appears at an annual festival of ugliness). The whole movie is as variable as a circus, but there are some priceless bits, including a virtuoso solo performance of Christ on the cross (1981). (JR) Read more

Endangered by their activism in Poland’s Solidarity struggle in 1981, a mother (Elzbieta Czyzewska) and son (John Cameron Mitchell) leave Warsaw for the U.S., staying with relatives (Viveca Lindfors, Deirdre O’Connell, John Christopher Jones) until they can move into an apartment of their own; their problems in adjusting to a new culture are exacerbated somewhat when the teenage son can’t accept the mother’s affair with their blue-collar landlord (Drew Snyder). This semiautobiographical independent film, written and directed by Louis Yansen (Thomas DeWolfe collaborated on the script), has persuasive performances by American actor Mitchell, Polish actress Czyzewska (the model for Sally Kirkland’s Anna), and the Swedish-born Lindfors, as well as a few awkward moments with some of the secondary players. One overall strength is its taboo-breaking position on the behavior of Americans toward foreigners. The mother and son initially encounter rudeness and unfriendliness almost everywhere they turn before their talentsthe mother as a Voice of America announcer, the boy as a violinisthelp them find some acceptance. (JR) Read more

My idea of hell is being forced at gunpoint to resee this 1981 atrocity (also known as Beatlemania, the Movie) based on a terrible stage musical. The basic idea is to feature impersonators of John, George, Paul, and Ringo performing tenth-rate versions of their songs and to make pretentious commentaries about their historical significance. Don’t say I didn’t warn you. Directed by Joseph Manduke; with Mitch Weissman, Ralph Castelli, David Leon, and Tom Teeley. (JR) Read more

After a decade’s absence, Jerry Lewis made his comeback in 1981 with this movie, which represents a throwback in some respects to the conditions of his first film as a director, The Bellboy: a low budget, discontinuous gags, and Florida locations (in this case suburban). But two decades separate that film from this one, and what Lewis comes up with here is both looser and more tragicnot merely in depicting the vain efforts of an out-of-work circus clown to hold down a steady blue-collar job, but in showing the effects of aging and lessened stamina in its star (reflected also in the tired, memorable features of Lewis’s straight man, Harold J. Stone, who plays his boss at the post office and the father of his girlfriend). The candor of this movie as self-portrait is at times almost terrifying; while some of the gags are genuinely funny, the depiction of an older Lewis trying to adjust to everyday American life also becomes a searing depiction of the fate of misfits in the Reagan era. Lewis has described this as his worst movie, but it also may be his most revealing one. With Susan Oliver and Steve Franken. (JR) Read more

This is a slightly different edit of a dialogue proposed and inaugurated by Ehsan Khoshbakht on July 5, 2016, edited by him, and published in the British Council’s online Underline magazine on July 8. — J.R.

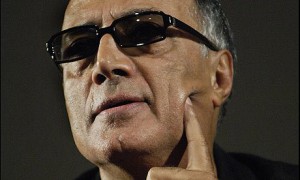

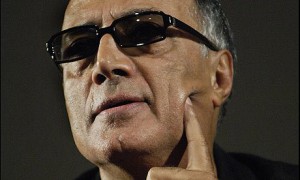

Abbas Kiarostami (1940-2016), arguably the greatest of Iranian filmmakers, was a master of interruption and reduction in cinema. He, who passed away on Monday in a Paris hospital, diverted cinema from its course more than once. From his experimental children’s films to deconstructing the meaning of documentary and fiction, to digital experimentation, every move brought him new admirers and cost him some of his old ones. Kiarostami provided a style, a film language, with a valid grammar of its own. On the occasion of this great loss, Jonathan Rosenbaum and I discussed some aspects of Kiarostami’s world. Jonathan, the former chief film critic at Chicago Reader, is the co-author (with Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa) of a book on Kiarostami, available from the University of Illinois Press. – Ehsan Khoshbakht

Ehsan Khoshbakht: Abbas Kiarostami’s impact on Iranian cinema was so colossal that it almost swallowed up everything before it, and to a certain extent after it. For better or worse, Iranian cinema was equated with Abbas Kiarostami. Read more

Subtitled The Unlimited Readings, this 1981 Marguerite Duras feature is one of her most strongly minimalist, consisting mainly of an offscreen poetic dialogue between a sister and brother about their memories and their incestuous feelings for each other (spoken by Duras and her companion Yann Andrea) and shots of empty beaches and a virtually deserted hotel lobby where one occasionally glimpses Bulle Ogier (and, less often, Andrea). The results are not devoid of interest, but far less absorbing and resonant than Duras’ India Song and Le camion. (JR) Read more