From Evergreen Review, April 1969. –- J.R.

TO THE EDITOR:

Now that Cahiers du Cinéma in English is no longer with us, it is good that Evergreen Review will be filling in part of the gap by translating and publishing “those articles from its pages which we feel are of greatest interest to our readers.” But already with its first selection —“Death at Dawn Each Day: An Interview with Ingmar Bergman” (No. 63) –- I am led to wonder how carefully, or thoughtfully, Evergreen intends to handle this task. If the last part of the interview is to be chopped off, one might at least hope that Evergreen would acknowledge this in some way, however euphemistically.

In addition, despite a translation that reads better and seems more accurate than most of the ones in Cahiers in English, the same problem of translating French film titles instead of using their American equivalents is bound to create confusion in the minds of most of your readers. For the record, Le Visage is The Magician, not Faces (which, as your translator apparently doesn’t realize, is a recent American film by John Cassavetes); Les Communiants is Winter Light, not The Communicants; and L’Été avec Monika is just Monika. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 13, 1987). — J.R.

HOPE AND GLORY

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by John Boorman

With Sebastian Rice Edwards, Sarah Miles, David Hayman, Derrick O’Connor, Susan Wooldridge, Sammi Davis, and Ian Bannen.

Disasters sometimes take on a certain nostalgic coziness when seen through the filter of public memory. Southerners’ recollections of the Civil War and the afterglow felt by many who lived through the Depression are probably the two strongest examples of this in our national history — perhaps because such catastrophes tend to bring people together out of fear and necessity, obliterating many of the artificial barriers that keep them apart in calmer times. When I attended an interracial, coed camp for teenagers in Tennessee in the summer of 1961, shortly after the Freedom Rides, the very fact that our lives were in potential danger every time we left the grounds en masse — or were threatened with raids by local irate whites — automatically turned all of us into an extended family. Considering some of the cultural differences between us, I wonder if we could have bridged the gaps so speedily if the fear of mutually shared violence hadn’t been so palpable.

The images that we inherit of other people’s disasters are often suffused by a similar nostalgia. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, October 1974 (Vol. 41, No. 489). Postscript: Thanks (once again!) to Ehsan Khoshbakht for providing me with an extra illustration for this review. — J.R.

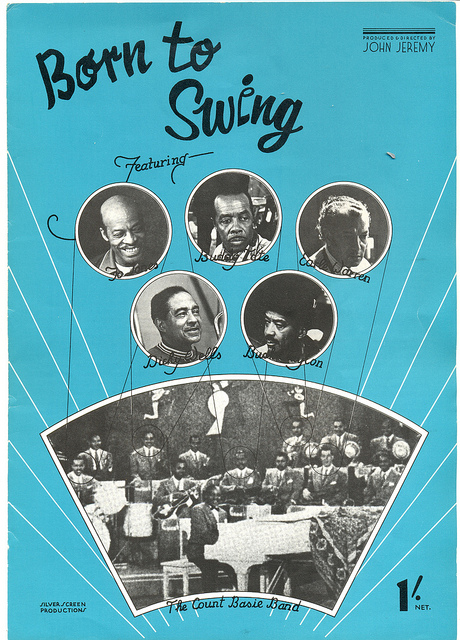

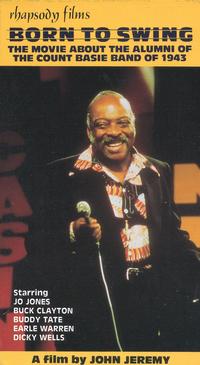

Born to Swing

Great Britain, 1973

Director: John Jeremy

Dist–TCB. p.c–Silverscreen Productions. p–John Jeremy. p. manager—

Angus Trowbridge. sc–John Jeremy. ph–Peter Davis, Tohru Nakamura.

photographs–Ernie Smith, Valerie Wilmer. ed–John Jererny. m–Buddy

Tate, Earle Warren, Joe Newman, Dicky Wells, Eddie Durham, Snub

Mosley, Gene Ramey, Tommy Flanagan, Jo Jones, The Count Basie

Band (1943). m. rec—Fred Miller. sd. rec—Ron Yoshida. sd. re-rec—

Hugh Strain. narrator–Humphrey Lyttelton. with–Buck Clayton, John

Hammond, Andy Kirk, Jo Jones, Albert McCarthy, Gene Krupa, Snub

Mosley, Joe Newman, Buddy Tate, Earle Warren, Dicky Wells. 1,773 ft.

49 mins. (16 mm.).

This engaging jazz film has both a general subject and a specific

one. Generally, it is about American swing music of the past;

specifically, its main focus is six veterans of Count Basie’s band in

the present. Interspersed with a 1943 clip of the Basie band inspiring

some athletic dancers are album covers, flurries of sheet music,

neon signs, and a string of short reminiscences: by Andy Kirk,

about his stint with the Eleven Clouds of Joy; Snub Mosley, about

New York in the Thirties; the doorman at Jimmy Ryan’s, about

52nd Street; Gene Krupa, mainly about himself. Read more