For my second Tuesday screening at the Metrograph on January 18. Commissioned by Metrograph and posted by them on December 2, 2021. — J.R.

What do we mean when we talk about exploitation films? Most often, we’re alluding to sensation-driven movies that are politically incorrect, like those of Quentin Tarantino. And what are we saying when we complain that we can’t identify with any of a film’s characters? Some of us tend to resist movies that make us think both inside and outside their stories rather than swallow them whole, and identifying with characters is arguably one way of limiting our thought processes.

What’s singular about many of the films of Yasuzô Masumura (1924–1986) is that they’re intellectual forms of exploitation—politically incorrect experiences that are consciously sociopolitical critiques, unlike the roller-coaster rides of Tarantino. You might even say that they shock us into thinking. But it’s hard to make too many generalizations about someone who made 58 films, mostly assignments at Daiei before that studio closed in 1971. A fair number of Masumura’s films are routine time-wasters, but the best of them, which for me include at least three of the five Metrograph is showing—Giants and Toys (1958), Black Test Car (1962), and Irezumi (1966)—are quite remarkable. The other two are The Black Report (1963), a fair to middling noir, and Blind Beast (1969), a cruder exploitation item that has its passionate defenders.

After receiving an undergraduate law degree at Tokyo University, Masumura became a part-time philosophy student there while starting to work at Daiei, where he would eventually become assistant director to both Kenji Mizoguchi and Kon Ichikawa. Before that would happen, he won a scholarship to study film at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in Rome, where one of his mentors was reportedly Antonioni (who later became both an influence and one of Masumura’s most faithful fans). Back in Japan, after returning to Tokyo University, where he wrote a dissertation on Kierkegaard, he started his filmmaking career with Kisses (1957)—a romance about alienated youth whose title was already a provocation (kisses had been forbidden by Japanese film censors before the war, and were still relatively sparse on Japanese screens outside of foreign releases). The film helped to win the enthusiastic support of Nagisa Ōshima, who soon afterward would embark on his own edgy first feature.

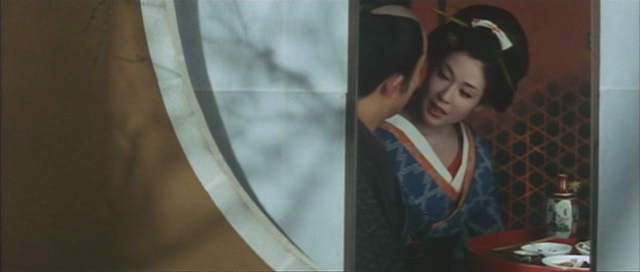

Giants and Toys, a grotesque satirical comedy that evokes Frank Tashlin, and the noirish Black Test Car are both industrial spy thrillers, a subgenre that was one of Masumura’s specialties. Irezumi is a period drama about tattooing, notable on at least three counts: it is one of three strong films he adapted from the great writer Junichiro Tanizaki; it stars the extraordinarily gifted and sensuous Ayako Wakao, a powerful actress Masumura discovered while working on Mizoguchi’s Street of Shame (1956) and who would subsequently star in at least 20 of his films and most of his masterpieces, including A False Student (1960), A Wife Confesses (1961), and Red Angel (1966); and it was shot in color by cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa (who also shot 1950’s Rashomon, 1953’s Ugetsu, and 1954’s Sansho the Bailiff). Masumura was said to have objected to Irezumi’s striking and gorgeous diptych compositions because he felt they distracted viewers from the story. “Some believe more in the image, others believe in the story,” he avowed in one interview. “Personally I believe in the story. Because images aren’t absolute, one can’t express everything with them.”

What Masumura was primarily interested in was a defiance of certain fundamental traits of Japanese culture, creating a cinema of crazy people, aspects of which can be found particularly in Giants and Toys and Black Test Car (where capitalism is depicted as a form of insanity) and Blind Beast (where a mad sculptor uses female bodies as his raw material). A film critic as well as a filmmaker, Masumura responded in a 1958 article to those who accused him of making bleak and tasteless cinema that lacked sentiment and featured comically exaggerated and unbelievable characters without any depiction of environment or atmosphere. Boasting that he was guilty as charged on all counts, Masumura replied as follows:

“I dislike sentiment. This is because sentiment in Japanese cinema consists of self-regulation, harmony, resignation, sorrow, defeat, and flight. The Japanese don’t think of dynamic vitality, conflicts, and death struggles or pleasure, victory, and pursuit as sentiment. … I dare to defend honest, coarse, and egotistic expression because the Japanese are so prone to restrain and suppress their desires and lose sight of their true emotions. … There is no such thing as an absolutely free expression of desire. Someone who exposed their raw desire could only be seen as insane. … But I am not interested in portraying a stable character who takes the measure of reality and adjusts the expression of his or her desires accordingly. I am not interested in depicting a human being with ‘human’ traits. I want to show an insane person who expresses his or her passion without shame, regardless of what people think.”[1]

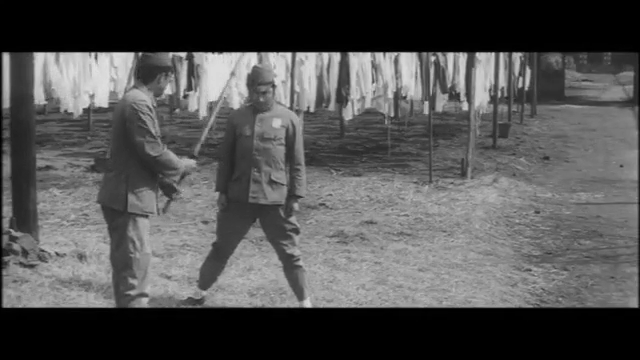

One way of seeing how this was played out in his work would be to consider his war films. According to scholar Earl Jackson Jr., Masumura designed his war films to subvert those that were deemed acceptable at the time in Japan: anti-war films that addressed viewers’ consciences, comedies, and spectacles. In his Hoodlum Soldier (1965), for instance, a Manchuria-set World War II comedy, all the slapping and bone-crunching shown and heard comes from Japanese soldiers brawling with other Japanese soldiers, and none of it involves the Chinese they’re fighting against. (Desertion, meanwhile, is treated as a sane and responsible activity.) Within the first few minutes of Red Angel, a Japanese nurse (Wakao) is raped by a Japanese soldier in the Sino-Japanese war. Much later, she offers to have sex with a morphine-addicted surgeon for a pint of blood that might save the life of the rapist—not because she forgives him but because she doesn’t want him to die thinking that she’s taking revenge. In Nakano Spy School (1966), everyone winds up betraying everyone else (as in the industrial thrillers) because the system itself is intrinsically rotten and promotes fanaticism. The narrator-hero graduates from officer training school in 1937 and tells his fiancée to wait a couple of years until his discharge. He never sees her again until he hears that she’s spying for the British, and is ordered to kill her. Needless to say, he makes love to her first—a seeming staple of this form of exploitation.

[1] Yasuzô Masumura, “Aru benmei: Jocho to shinjitsu to fun’iki ni se o mukete” (A Defense: Turning my Back on Sentiment, Authenticity, and Atmosphere), translation by Chika Kinoshita and Michael Raine.

Jonathan Rosenbaum maintains a web site archiving most of his writing at jonathanrosenbaum.net. His most recent book is Cinematic Encounters 2: Portraits and Polemics (2019).