1. Letter from Alain Resnais to Richard Seaver

(A “hasty” English translation by Francois Thomas)

Tuesday, October 20, 1970

Dear Dick,

Your letter of October 10 from Southampton [New York] arrived last night. Probably intersected with the one I sent on the 8th, containing answers to several questions you asked me. But — is it a feeling — you don’t seem to be aware of the one I sent you on September 9 (and I remember that you didn’t seem to have received one of the notes I sent from London at the end of July either). Anyway, I’m writing to you without waiting for the French postal workers’ strike announced for next Tuesday.

Perry had told me that he was happy with your letter and the contract and that everything was fine on that side. The distance between rue des Plantes and Dean Street makes it difficult to check. In any case, his silence is inexcusable and you can therefore feel free to have Konecky notify him of the loss of his rights (Unless he telegraphs money to you. That’s always a good thing. Paramount here was still talking about $10,000 as the total budget for a script!)

I always refuse to let a project be read and I had to take a lot on myself to give the material to Carlos [Clarens]. But he sounded so enthusiastic in promising me a reply from Gerald Ayres-Columbia within three days, with his plane leaving the next day, I feared I was missing a chance in case you were not in New York during Ayres’ brief stay with whom Carlos wanted you to have dinner.. What remains totally unclear to me is how you and Carlos were able to talk on the phone in such a vague way. I thought you were very friendly. You don’t seem to have received his letter either, which I will xerox for you tomorrow.

Yesterday, when Costa arrived from New York, he told me both how happy he had been to meet you and how much Paramount-N.Y. regretted not being able to help us. He left this morning with [Jorge] Semprun for London, still undeterred, to offer the case to [Robert] Littman-Metro-Goldwyn, with whom he works. [Costa-Gavras had already collaborated with Semprun on Z and The Confession.]

As soon as I read your letter, I phoned Semprun to inform him of Perry’s silence towards you for the last two months, i.e. the signed contract, and of your wish that only the “second draft” be used. Not sure you’re right about that. I always give people both the second draft and the shooting script, and I ask them to start with the second draft, read at least the first forty pages and then move on to the shooting script. But it’s probably my stickler side and in the end the questions are always: “What is it about? Who is in it? A voice over, isn’t that dangerous? Is there enough action to attract a mass audience? Why such a mammoth budget? Why shoot in the Vaucluse since there is nothing of the period?” [The Vaucluse refers mainly to La Coste, where Sade owned a castle.]

Apart from that I feel a bit bewildered because since 1949 I had never met so many rejections. In short, after Mag Bodard and the three British producers, Warner, Columbia and Paramount said no [ If Metro is negative too, it will be very serious because United Artists produced Muriel and Fox Je t’aime je t’aime.

Costa told me that, in case of a production miracle, it wouldn’t be too difficult for you, if you were given three weeks’ notice, to come in and work a fortnight after the script was finished. Right?

I have no experience of using a “professional agent” (the French equivalent hardly exists) to mount a production. If it doesn’t cost anything (you can guess what my financial situation is) and if you think there is a chance in this way…

Yes, a million dollars obviously scares the producers. But I don’t see any way to reduce this budget, which is rather likely to be insufficient.

I received a letter (and a script) from Californian filmmakers who, unable to find financing in the U.S., asked me to find them a French producer!

[The end of the letter is handwritten :]

I’m stopping because I’m very late. I’m glad you’re happy. Love to you both

A

2. Sade, Resnais, Lubitsch, MGM

Jonathan Rosenbaum

One of the main problems with treating Resnais as a formalist is that this risks overlooking the fact that serious formal innovation is always motivated by a search for new content—new content requiring a new form in order to be articulated. And from this standpoint, one could argue that the same Resnais who refused to film the Sadean rape that was scripted by Alain Robbe-Grillet for L’Année dernière à Marienbad would be (or at least would become) sufficiently curious about Sade as a character to devote a year with Richard Seaver developing this curiosity into a plan for an ambitious and expensive feature.

A few glosses on Resnais’ letter to Seaver (quite an unexpected document from a filmmaker who hated to write letters), starting with a couple of my own experiences and memories:

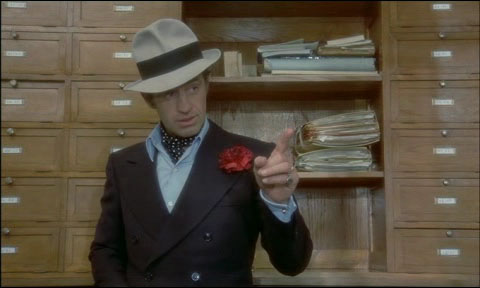

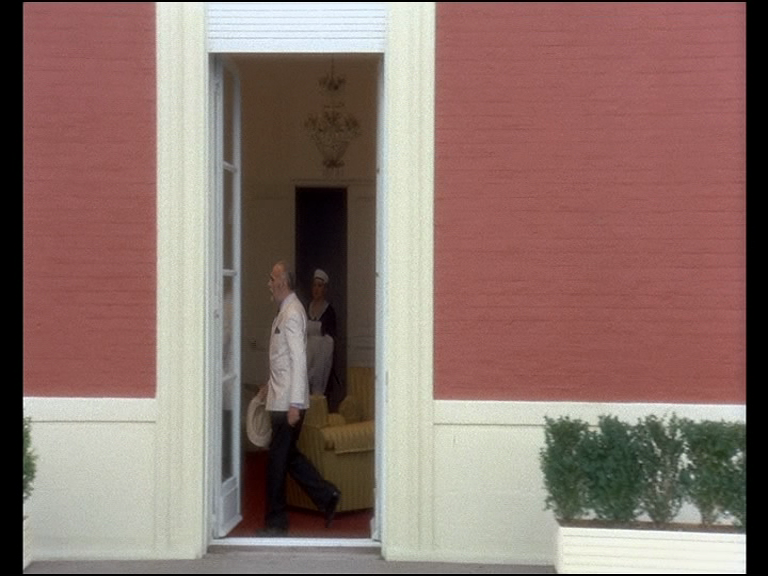

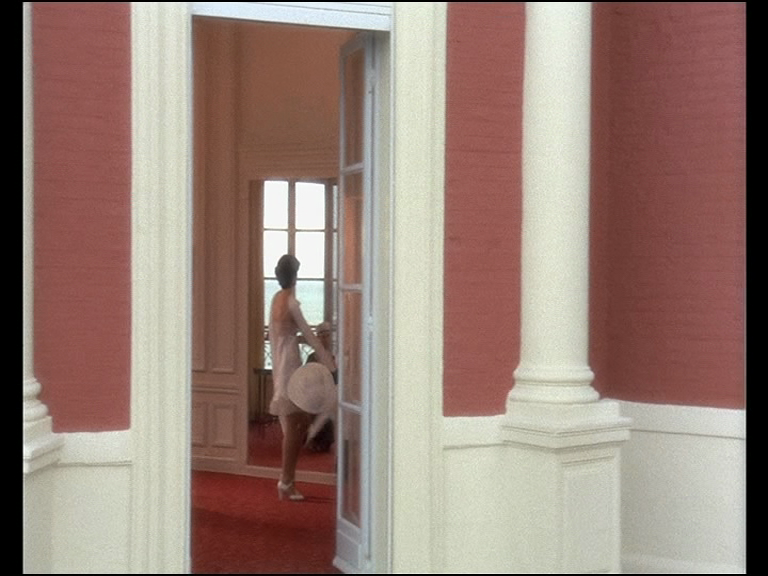

Visiting the soundstage at Épinay-sur-Seine on December 7, 1973, where Resnais was filming in a gargantuan, neo-Lubitschian studio set of Stavisky’s complex of offices in 1933, I interviewed him in one of its recesses during a shooting break about both Stavisky… and some of his unrealized projects. Here’s what I reported about the Sade project, called Délivrez-nous du bien, in the March-April 1974 Film Comment: “Resnais visited a lot of places where Sade lived and took photographs. The script was done in English for various reasons — to create a certain ‘distance,’ the restraints of French censorship at the time. Now that the same restraints no longer exist, Resnais feels that the potential shock value of the project has been decreased.” I am happy that we know much more about the project now.

A few specifics about the letter itself: “Carlos” was Carlos Clarens (1930-1987), a Cuban-born protégé of Henri Langlois and a friend of mine in Paris during this period. He appeared as himself in Los Angeles in Agnès Varda’s Lions Love in 1969 and he may have traveled there again in 1970, a few months after I first met him at the Cannes Festival, to interview George Cukor for the book he was writing about him, published in 1976. But Carlos had many friends and interests, so it’s hard to be sure about this. “Costa” was Costa-Gavras, Konecky was the attorney who negotiated Seaver’s contract, Gerald Ayres was the (uncredited) producer of Jacques Demy’s The Model Shop, and Robert Littman supervized MGM coproductions filmed in Europe such as David Lean’s Ryan’s Daughter, “Dean Street” in London was where the British Film Institute was then located, and rue des Plantes was the street in Paris where Resnais had an apartment.

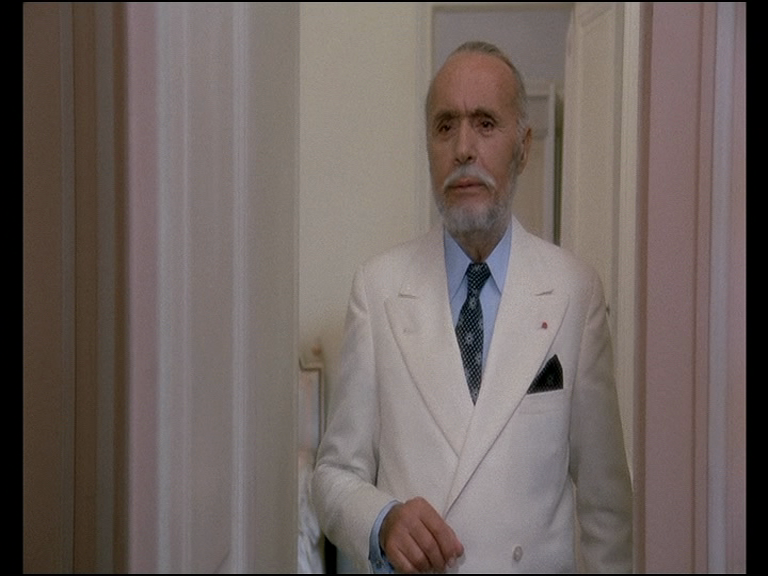

Resnais met Seaver in late 1959, during his first visit to New York, and although the Grove Press’s English translation of Robbe-Grillet’s screenplay for Last Year at Marienbad was carried out by the better-known Richard Howard (subsequently the key English translator of Barthes), Seaver translated both a draft of the Harry Dickson script and Jorge Semprún’s script for La guerre est finie during the mid-60s. The two of them began discussing the Sade project in April 1969. In May 1970, Dirk Bogarde, during the on-location shooting of Death in Venice, agreed to play Sade after reading Seaver’s script. (He had previously agreed to play Harry Dickson, but he would finally work for Resnais only on Providence, one of his most memorable roles.) The remainder of the cast was expected to be British, and the producer was also British (the very young Anthony Perry), but no further casting decisions were made. During the same month, Resnais contacted Marvel Comics artist Jim Steranko to design the sets for Délivrez-nous du bien in consultation with a British set designer, but after Resnais failed to strike a deal with Mag Bodard (the producer of the commercially unsuccessful Je t’aime je t’aime), Warners, Columbia, Paramount, and MGM, the project was finally abandoned around the end of that year.

Nurtured as a cinephile on the lavish pleasures of studio filmmaking as much as the Young Turks at Cahiers du Cinéma were—perhaps even more than them, if one considers that Resnais reportedly introduced André Bazin to German Expressionist cinema—Resnais periodically required a few of the trappings of MGM or UFA to upholster some of his projects, making the sumptuous melancholy of Ben-Hur composer Miklós Rózsa a far more essential ingredient for Providence than Bernard Herrmann could ever be for the appropriations of De Palma attempting to copy Hitchcock. The crucial distinction that separates Resnais’ use of cinematic inspirations from those of the Movie Brats and links him more to Godard’s critical and creative extensions and elaborations of his sources is a predilection for mixing and merging his visual models, preferring application to duplication, so that emulating the camera’s encirclement of a Lubitschian hotel exterior in Stavisky… entails not a simple recreation of a Paramount architectural landscape but a sharp, even rude encounter of that setting with an angular MGM heroine inside the hotel bathed in swank MGM colors and fabrics.

Yet unlike Godard, Resnais was a Surrealist, so that his desire to give the Divine Marquis the opulent MGM treatment might well have been a simple desire to ponder and discover what such a shocking collision might have produced. Surely not a Richard Thorpe period adventure; but whatever he might have had in mind, we’ll never know.