From the Chicago Reader (July 10, 1992). For more on Endfield, see Brian Neve’s excellent new biography, The Many Lives of Cy Endfield: Film Noir, the Blacklist, and Zulu, as well as my subsequent Reader article about him and my essay “Pages from the Endfield File,” which grew out of the preceding two pieces and is reprinted in my 1997 collection Movies as Politics. This particular piece has been upgraded in terms of illustrations. — J.R.

FILMS BY CY ENDFIELD

The role of a work of art is to plunge people into horror. If the artist has a role, it is to confront people — and himself first of all — with this horror, this feeling that one has when one learns about the death of someone one has loved. — Jacques Rivette in an interview, circa 1967

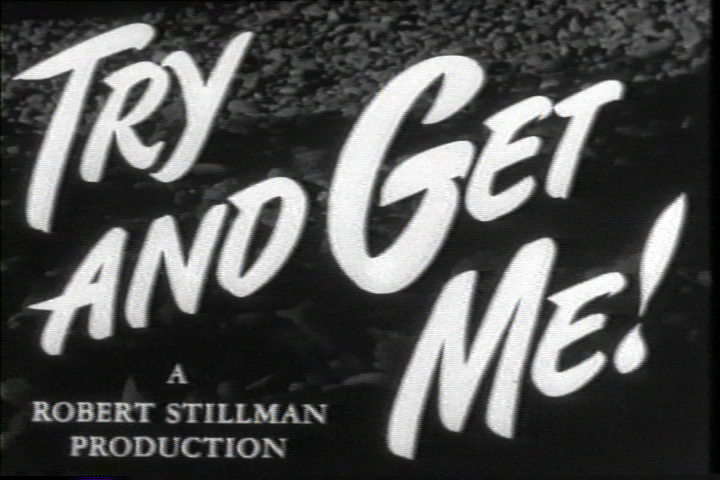

Cyril Raker Endfield, who will turn 78 this November, is the sort of filmmaker auteurist critics like to call a “subject for further research.” To the best of my knowledge, he has directed 21 features — the first 7 in the United States between 1946 and 1951, the remainder in England, continental Europe, and South Africa between 1953 and 1971 — and worked on the scripts for most of them, as well as on the scripts of two Joe Palooka films (apart from the two he directed), a Bowery Boys picture (Hard Boiled Mahoney, 1947), Douglas Sirk’s Sleep My Love (1948), a prison picture called Crashout (1955), Jacques Tourneur’s Curse of the Demon (1958), and Zulu Dawn (1979), a sort of prequel to Endfield’s only hit, Zulu (1964). Read more

Bing Crosby stars as a carefree troubadour who settles down and helps to open a restaurant in order to keep his little friend (Edith Fellows) out of an orphanage; Madge Evans (Hallelujah, I’m a Bum!) is the skeptical social worker who gradually falls for him. Directed by Norman Z. McLeod, this Depression-era musical (1936) is hokey but likable, its cloying sentimentality made bearable by its casual but sincere populism. Louis Armstrong, who reunited with Crosby on-screen 20 years later in High Society, is just as wonderful here. 81 min. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader, November 1, 1987. — J.R.

Alan Rudolph’s movie begins promisingly: Mike (Tim Hutton), out of work in the mid-40s (in black and white), dies in an accident and finds himself in heaven (in color), where he’s greeted by his amiable Aunt Lisa (Maureen Stapleton), and shortly falls in love with Annie (Kelly McGillis), an unborn soul. Heaven here is rather like Ray Bradbury’s Mars, a site of nostalgic wish fulfillments, and if Rudolph and screenwriters Bruce A. Evans and Raymond Gideon had only remained there, the movie might have somehow sustained its fragile, otherworldly charm. But Annie leaves to be born on earth, and Mike, who’s allowed to be reborn, is given 30 years to find her again. Inexplicably, the film remains in color as it returns to earth; the new selves of Annie and Mike still look the same, but how they’re supposed to find one another with fresh identities and nearly blank memories is not made clear, and vagueness gradually gives way to muddleheadedness. Although a string of cameos by nonactors (including novelist Tom Robbins and various rock singers) leads to some awkward moments, Rudolph still shows some talent in handling professionals (such as Ann Wedgeworth and Don Murray, as well as the leads), though he’s invariably better off when directing his own scripts (e.g., Read more