SPECIAL CITATION for a film awaiting American distribution: Sieranevada (Romania) Cristi Puiu

FILM HERITAGE AWARD: Kino Lorber’s 5-disc collection “Pioneers of African-American Cinema”

BEST ACTOR

*1. Casey Affleck (65) – Manchester by the Sea

2. Denzel Washington (21) – Fences

3. Adam Driver (20) – Paterson

BEST ACTRESS

*1. Isabelle Huppert (55) – Elle and Things to Come

2. Annette Bening (26) – 20th Century Women

2. Sandra Hüller (26) – Toni Erdmann [tied with Bening]

BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR

*1. Mahershala Ali (72) – Moonlight

2. Jeff Bridges (18) – Hell or High Water

3. Michael Shannon (14) – Nocturnal Animals

BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS

*1. Michelle Williams (58) – Manchester by the Sea

2. Lily Gladstone (45) – Certain Women

3. Naomie Harris (25) – Moonlight

BEST SCREENPLAY

*1. Manchester by the Sea (61) – Kenneth Lonergan

2. Moonlight (39) – Barry Jenkins

3. Hell or High Water (16) – Taylor Sheridan

BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY

*1. Moonlight (52) – James Laxton

2. La La Land (27) – Linus Sandgren

3. Silence (23) – Rodrigo Prieto

BEST PICTURE

*1. Moonlight (54)

2. Manchester by the Sea (39)

3. La La Land (31)

BEST DIRECTOR

*1. Barry Jenkins (53) – Moonlight

2. Read more

Note: I saw Samuel Maoz’s Foxtrot too late for inclusion, but would have placed it in or near the top ten if I had seen it earlier.

1. 24 Frames (Kiarostami)

2. Twin Peaks: The Return (Lynch)

3. Let the Sun Shine In (Denis)

4. Downsizing (Payne)

5. Barbs, Wastelands (Marta Mateus)

6. Mudbound (Rees)

7. Phantom Thread (Anderson)

8. Faces Places (Varda & JR)

9. Lady Bird (Gerwig)

10. Marjorie Prime (Almereyda)

11. Ava (Foroughi)

12. The Shape of Water (del Toro)

13. The Meyerowitz Brothers (New & Selected) (Baumbach)

14. Paradise (Konchalovsky)

15. The Lost City of Z (Gray)

16. The Motive (Cuena)

17. Ex Libris: The New York Public Library (Wiseman)

18. Boom for Real (Driver)

19. Golden Years (Téchiné)

20. Professor Marsten and the Wonder Women (Robinson) Read more

An updated revision of a 1999 essay, commissioned by and posted on Slate on May 24, 2017. — J.R.

One of the paradoxes of conspiracy thrillers is that seeing the world as if it were as orderly and coherent as a work of art is both satisfying and terrifying. If everything makes sense, then it’s hard to avoid the premise that someone somewhere is creating that coherence–either God or an equally unseen puppet master. And the fact that we don’t see the strings being pulled means that our imaginations are invited to sketch them in, making us co-conspirators in the process: And opting out of this creative participation means accepting chaos: “If there is something comforting—religious, if you want—about paranoia,” declares Thomas Pynchon in Gravity’s Rainbow, “there is still also anti-paranoia, where nothing is connected to anything, a condition not many of us can bear for long.”

It’s a tradition that harks back to Louis Feuillade’s silent serial of 1915-1916, Les vampires, about a gang of ingenious working-class criminals headed by a beautiful woman and preying on the rich—a crime thriller evoked in Olivier Assayas’ 1996 dark comedy about a contemporary remake, Irma Vep. Read more

A much shorter version of this was just posted by DVD Beaver:

Top Blu-ray Releases of 2017:

1. Othello (Orson Welles, 1952) Criterion Collection

2.Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project No. 2 (Limite — Mário Peixoto, Revenge — Ermek Shinarbaev, Insiang — Lino Brocka, Mysterious Object at Noon — Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Law of the Border — Lütfi Ö. Akad, Taipei Story — Edward Yang) — Criterion Collection

3. Vampir Cuadecuc (Pere Portabella, 1971) UK Second Run Features

4. The 4 Marx Brothers at Paramount (The Cocoanuts, Animal Crackers, Monkey Business, Horse Feathers, Duck Soup) (1929-1933) RB Arrow UK

5. Anatahan (Josef von Sternberg, 1953) Kino

6. A Brighter Summer Day (Edward Yang, 1991) RB Criterion UK

7. Moses and Aaron (Danièle Huillet, Jean-Marie Straub, 1973) Grasshopper Film

8. Letter from an Unknown Woman (Max Ophüls, 1948) Olive Signature

9. Lost in Paris (Dominique Abel, Fiona Gordon, 2016) Oscilloscope Pictures

10. A New Leaf (Elaine May, 1971) Olive Signature

A major reason for listing Criterion’s Othello first is that it includes the digital premieres of not one and not two but three Orson Welles features: both of his edits of Othello available with his own soundtracks, heard for the first time in the U.S. Read more

Researching Iranian cinema, even contemporary Iranian cinema, can sometimes be a dicey undertaking, in part because of the variant spellings of names and even a few film titles. I thought enough of Seyyed Reza Mir-Karimi ‘s first feature, The Child and the Soldier (2000), to include it on my list of my 1000 favorite films, included as an appendix in my 2004 collection Essential Cinema. And Fred Camper thought enough of his second feature, Under the Moonlight (2001), to begin his capsule review for the Chicago Reader by writing, “A refreshing version of Islam in which charity and justice are more important than rigid adherence to rules.” And now that I’ve seen his latest feature, which is Iran’s official entry for this year’s Academy Awards, Today — or Today!, as it appears to be written on the screen in Persian -– it’s clear that this director qualifies as a master. But now (today) his name is mainly given in Western sources as Reza Mirkarimi, without the Seyyed or the hyphen, so when I looked up this name on my own web site, I could find nothing. So it seems both ironic and ironically appropriate that the most ethical and humanist cinema we can find in the world today both engages directly with and is often confounded by our ignorance about the world we inhabit. Read more

From the Chicago Reader‘s blog, the Bleader. — J.R.

Holiday Jitters

Allied Advertising recently informed me that the Ben Stiller comedy Night at the Museum is being previewed only to the daily press, not to weekly reviewers — which naturally raises the question of whether the company in question (Twentieth Century Fox) is deciding in advance that we weekly reviewers won’t like this release. Whether that’s the meaning of their strategy or not, it does show a kind of uncertainty that is much more general among the so-called majors. For instance, Warner Brothers has at this pointed shifted the Chicago opening date of Clint Eastwood’s Letters From Iwo Jima several times, with the result that it’s bounced on and off my ten-best list according to whether it’s opening here in 2006 or 2007. New York and Los Angeles reviewers get to consider Flags of Our Fathers and Letters From Iwo Jima as part of the same package; Chicago reviewers don’t.

I differ from some of my local colleagues in refusing to consider 2007 releases for my 2006 list just because many of the film companies persist in treating Chicago as a cow town in contrast to New York and Los Angeles — both of which will be premiering Letters from Iwo Jima this year. In

Read more

Posted on Film Comment‘s blog, November 16, 2012. — J.R.

Much as Godard’s special brand of cultural tourism quickly became a dominant influence at international film festivals half a century ago, the literal tourism of the late Chris Marker became a major reference point in many of the edgiest offerings at the Viennale, celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. Fittingly, the last to date of the festival’s annual commissioned one-minute trailers, 19 of which were just issued on a DVD, was by Marker himself — a somewhat jaundiced view of the “perfect” film viewer as sought by Méliès, Griffith, Welles, and Godard, eventually and rather sadly achieved in the sad figure of Osama bin Laden watching a Tom and Jerry cartoon on a TV set.

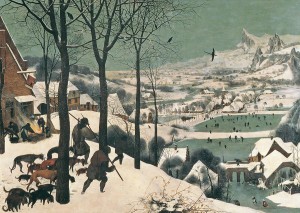

Marker’s more benign influence was especially evident in Jem Cohen’s magisterial Museum Hours, a luminous mix of fiction and essay set in Vienna itself, where it takes the form of a casual friendship developing between a guard at the Kunsthistorisches Art Museum (played by Bobby Sommer — a familiar and friendly Viennale presence, who has worked for many years at its guest office) and a Canadian tourist (Mary Margaret O’Hara) who arrives to visit a dying cousin and turns up at the museum. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 16, 2007), slightly corrected (in terms of title and running time).. — J.R.

If Daffy Duck ever became a film critic informed by Lacanian psychoanalysis, this three-part English entertainment (2006) by Sophie Fiennes would surely qualify as his Duck Amuck. Theorist Slavoj Zizek, inside beautifully constructed sets matching various films’ locations, lectures provocatively and dynamically about 43 screen classics, often sputtering like Daffy himself. Hitchcock and Lynch are favored, but among the many other filmmakers considered are Coppola, Lang, Powell, and Tarkovsky. Zizek is especially sharp about manifestations of the maternal superego in Psycho and The Birds, maverick fists in Dr. Strangelove and Fight Club, and voices in The Great Dictator and The Exorcist. 143 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

The following short essay was commissioned by the Walker Art Center in early 2007 for a brochure accompanying a retrospective (“Michel Gondry: The Science of Dreams”) presented between May 11 and June 23, and a Regis Dialogue that I conducted with him on June 23. –J.R.

What’s sometimes off-putting about the postmodernity of music videos is tied to both the presence and absence of history in them — the dilemma of being faced simultaneously with too much and too little. On the one hand, one sees something superficially resembling the entire history of art — often encompassing capsule histories of architecture, painting, sculpture, dance, theater, and film — squeezed into three-to-five-minute slots. The juxtapositions and overlaps that result can be so violent and incongruous that the overall effect is sometimes roughly akin to having a garbage can emptied onto one’s head. Yet on the other hand, radical foreshortenings and shotgun marriages of this kind often have the effect of abolishing history altogether, making every vestige of the past equal and equivalent to every other via the homogenizing effect of TV itself. Back in 1990, sitting through nearly eight hours of a touring show called “Art of Music Video,” I was appalled to discover that the two most obvious forerunners of music videos, soundies from the 40s and Scopitone from the 60s, were neither included in the show nor even acknowledged in its catalog’s history of the genre. Read more

Here are five more of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007). — J.R.

Scene

1957 / Paths of Glory – Timothy Carey kills a cockroach.

U.S. Director: Stanley Kubrick. Cast: Ralph Meeker, Timothy Carey.

Why It’s Key: A quintessential character actor achieves his apotheosis when his character kills a bug.

To cover up his vain blunders, a French general (George Macready) in World War I orders three of his soldiers (Ralph Meeker, Joe Turkel, Timothy Carey), chosen almost at random, to be court-martialed and then shot by a firing squad for dereliction of duty, as an example to their fellow soldiers. When their last meal is brought to them, they can mainly only talk desperately about futile plans for escape and the hopelessness of their plight. Then Corporal Paris (Meeker) looks down at a cockroach crawling across the table and says, “See that cockroach? Tomorrow morning, we’ll be dead and it’ll be alive. It’ll have more contact with my wife and child than I will. I’ll be nothing, and it’ll be alive.” Ferrol smashes the cockroach with his fist and says, almost dreamily, “Now you got the edge on him.” Read more

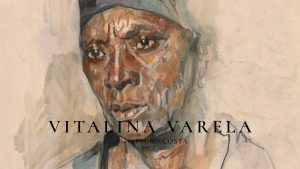

Written in late 2019 for Grasshopper Film’s digital release in 2020 of Pedro Costa’s masterpiece, recently selected as Portugal’s official submission for best international feature at the 93rd Academy Awards. — J.R.

“A film with no commercial prospects whatever,” lamented The Nation’s Stuart Klawans, in the course of his passionate defense, after it won both the Golden Leopard and best actress awards in Locarno and the Silver Hugo in Chicago, among other festival prizes. Soon afterwards, Film Comment announced on its cover, “Pedro Costa’s Breathtaking Vitalina Varela Goes to Sundance,” and it was also declared the best film of 2019 by Roger Koza’s international poll of 169 critics, filmmakers, and programmers, beating even Quentin Tarantino’s very-commercial Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood by eleven votes.

How to explain the appeal of a movie named after a real person, a displaced “non-professional” who is also its star? Or the nature of a film driven by its refusal to separate art from life or fiction from non-fiction — feeling more like a place to visit or a person to hang out with, and less like an event or a story?

Seemingly shared by Film Comment and Klawans is the assumption that the fate of Vitalina Varela is tied to commerce — something we can assume as well about the fate of Vitalina the person. Read more

Note: items followed by “(i)” have been reformatted and are also illustrated. (There are a few long reviews that appear on this site twice, once with illustrations and once without, although I’ve started to delete the non-illustrated duplications whenever I spot them.) For some strange reason, one of my long reviews, of both Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace and Trekkies, which appeared in the May 21, 1999 issue of the Chicago Reader under the title “Summer Camp,” didn’t make it onto either the Reader’s web site or my own until I recently copied it here. (I’ve also added another text missing from both sites, from the same year, on the four-hour Greed, which I already had in digital form because it was reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema.) Still missing from both sites is my brief ten best piece (actually, 20 best) for 2006, which appeared at some point in December 2006 or January 2007. If readers spot any errors here, I would welcome hearing about them, at jonathanrosenbaum at earthlink dot net.

***

Abigail’s Party, 1/10/92 (i)

The Abyss, 8/11/89 (i)

The Accidental Tourist, 1/13/89 (i)

The Accompanist, 1/28/94 (i)

Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, 3/4/94 (i)

The Actor, 4/11/97 (i)

An Actor’s Revenge, 6/3/88 (i)

The Adopted Son, 4/2/99 (i)

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, 3/17/89 (i)

The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D, 6/10/05 (i)

Aerograd, 6/7/02 (i)

The Affair of the Necklace, 12/21/01 (i)

After the Sunset, 11/18/04 (i)

Against the Day (novel), 12/1/06 (i)

The Age of Innocence, 9/17/93 (i)

A.I. Read more

If memory serves, this review provoked more hate mail than anything else I ever wrote for the Reader, very little of which engaged with my actual argument — a response I tend to correlate with this country’s unreasoning and irrepressible infatuation with and worship of serial killers as virtual religious icons (roughly akin to rock musicians who die of drug overdoses). But according to the Reader, it is also one of my most widely read Reader pieces. It ran in the November 8, 2007 issue, a little less than four months before I retired from the paper. — J.R.

No Country for Old Men | Written and Directed by Ethan and Joel Coen

The first thing we demand of a wall is that it shall stand up. If it stands up, it is a good wall, and the question of what purpose it serves is separable from that. And yet even the best wall in the world deserves to be pulled down if it surrounds a concentration camp. —George Orwell

I tend to get flustered when people ask me what I look for in movies, so I’m wary of theorizing too much about what other people want from them. Moviegoers generally seem to fall into one of two categories: those looking for experiences similar to ones they’ve already had and those looking for experiences that are new. Read more

Posted on the Chicago Reader‘s blog, February 16, 2007. It’s nice to report that both Pete Kelly’s Blues and Too Late Blues are now readily available, on both DVD and Blu-Ray. — J.R.

The market value of a missing movie

Don’t ask me how, but I recently had a chance to resee Jack Webb’s Pete Kelly’s Blues (1955), a terrific, atmospheric, period noir in Cinemascope and WarnerColor about a cornet player (Webb) in a Dixieland band in 1927 Kansas City (after an evocative prologue in 1915 New Orleans and 1919 Jersey City showing us where and how Pete Kelly came by his cornet). It’s got an amazing cast: Edmond O’Brien, Janet Leigh, Peggy Lee, Lee Marvin, Andy Devine (in a rare and very effective noncomic role), Ella Fitzgerald, and even a bit by Jayne Mansfield as a cigarette girl in a speakeasy. The screenplay, which deservedly gets star billing in the opening credits, is by Richard L. Breen, onetime president of the Screen Writers Guild and a key writer on Webb’s Dragnet, and it’s full of wonderful and hilarious hardboiled dialogue and offscreen narration by Webb. (When a flapper played by Leigh says to Kelly that April is her favorite month, he replies, “If you like it so much, I’ll buy it for you.”)

Read more

My Spring 2014 DVD column for Cinema Scope, posted in March. — J.R.

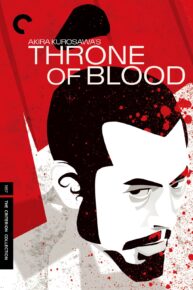

There’s no question that DVDs and Blu-rays are fostering new viewing habits and also new critical protocols and processes in sizing up what we’re watching. A perfect example of what I mean is Criterion’s brilliant idea to release Kurosawa Akira’s Throne of Blood (1957) with two alternative sets of subtitles by Linda Hoaglund and the late Donald Richie, both of whom were also commissioned to write essays explaining the rationales and methodologies of their very different translations—a move that I already wrote about and praised in my fourth DVD column for this magazine, just over a decade ago. So I’m very happy to find these subtitles and essays preserved in Criterion’s new dual-format edition, providing an invaluable pedagogical tool that was (and still is) unavailable to anyone seeing Throne of Blood theatrically.

In 1963, after seeing Jules and Jim, I had the pleasure of reading Roger Greenspun about it in Sight & Sound. I regret this option isn’t readily available today, but I have to admit that in Criterion’s new dual-format edition, I have many other things I can turn to—I’m especially grateful for the dialogue between Dudley Andrew and Robert Stam, an interview with Truffaut’s co-writer Jean Gruault, and a fascinating documentary about the film’s real-life models, all of which, perversely or not, held my interest longer than seeing the film all the way through for the umpteenth time. Read more