From the Chicago Reader (April 30, 2004). — J.R.

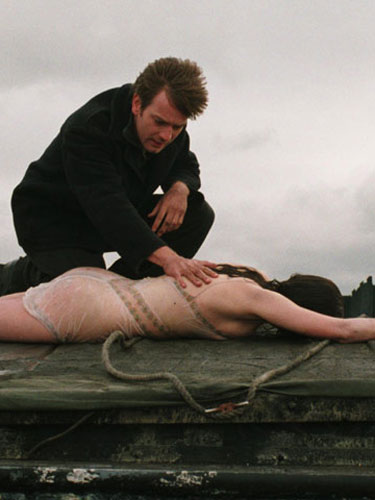

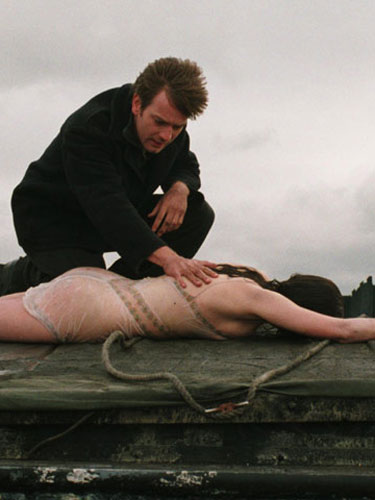

David Mackenzie’s compelling and authoritative adaptation of Alexander Trocchi’s 1953 novel revolves around a nihilistic bargeman (perfectly embodied by Ewan McGregor) who works the canals between Edinburgh and Glasgow and spends all his free time reading and screwing (often adulterously). This emotional detachment is often treated as an existential position, so the story occasionally suggests a beat version of Camus’ The Stranger, with the images’ sensual and erotic power often superseding any literal meaning. Despite the flashback structure, this is a film in which mood matters more than plot, while the hero’s heroic stature steadily shrinks. All in all, a very impressive second feature. With Tilda Swinton (The Deep End), Peter Mullan (My Name Is Joe), and Emily Mortimer. NC-17, 93 min. Century 12 and CineArts 6, Pipers Alley.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 7, 2005). — J.R.

Ten film critics’ polls in Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, Toronto, and Washington, D.C., have named Sideways the best movie of the year. I don’t know whether to laugh or cry.

It’s not that I have anything against comedies; last year Down With Love was second on my ten-best list. Besides, Sideways has a dark side — its infantile hero (Paul Giamatti) steals from his mother, and his infantile sidekick (Thomas Haden Church), who’s about to be married, compulsively cheats on his fiancee. They behave as if the world beyond southern California doesn’t exist, but the movie doesn’t seem to realize it. And like most American mainstream movies, it dances around class issues without ever facing them.

If my colleagues who love this movie, many of whom I admire, are implying that it contains valuable life lessons, I wish they’d tell me what they are. Giamatti is an acerbic loser hero who’s eventually given a ray of hope, like the Woody Allen hero of 20 or 30 years ago but without the wisecracks. So is regressing to that moviemaking model the proudest achievement of world cinema in 2004? Did the critics find something comforting, even affirmative, about its provincialism? Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 3, 1999). — J.R.

El Valley Centro

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by James Benning.

El Valley Centro, James Benning’s latest feature, is a fairly minimalist effort consisting of 35 shots, each of them two and a half minutes long, filmed in direct sound with a stationary camera in California’s Central Valley. About halfway through I found myself, to my surprise, thinking about Joseph Cornell’s boxes, those surrealist constructions teeming with fantasy and magic — dreamlike enclosures that make it seem appropriate that Cornell lived most of his life on a street in Queens called Utopia Parkway.

Benning’s films are typically about farmland, deserts, or industrial landscapes. The two features preceding this one are Four Corners, shot around the point where New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah meet, and Utopia, shot in desert country starting in Death Valley and heading south across the Mexican border. Benning hails from Wisconsin, and most of his early films are made up of midwestern landscapes. He moved to the west coast several years ago to teach at Cal Arts, and ever since he’s been shooting various kinds of midwesternlike emptiness and decay in the western states. Two years ago he started offering free December screenings of his new films at a private loft in Wicker Park, when he was back for the holidays, and apart from screenings at Cal Arts, these have been the films’ American premieres. Read more

Now that I’ve seen three of the most recent half-dozen features of Jon Jost — Coming to Terms (2013, Butte, Montana), Blue Strait (2014, Port Angeles, Washington), and They Had it Coming: True Gentry County Stories (2015, Stanberry, Missouri), in that order — I find myself, unlike certain others (including Jost himself), preferring the third to the second and the second to the first. The reason why is that the basic theme of Jost’s narrative films for quite some time has been the tragic story of American men, some of them patriarchal, others simply burnt-out cases, losing their all-American souls — a theme that to my mind he already gave near-perfect expression to in his 1977 Last Chants for a Slow Dance (dead end) and which he has been spinning out periodically in diverse variations ever since. But to judge from the developments between these three recent features, this may be a story that Jost may finally be turning away from — for the sake of non-narrative meditations (especially in much of Blue Strait) and the stories of others (as in They Had it Coming), others whom in some cases may not even have discernible souls to lose. And for me, these are positive developments for a prodigious independent artist whose productivity is so difficult to chart that his eight separate blogs and two separate web sites make it even harder to track in its various forms and dispersals. Read more

Written for the Second Run DVD of Pedro Costa’s Casa de Lava, released in the U.K. in 2012, and developed from separate articles in the Chicago Reader, November 15, 2007, and the Portuguese collection cem mil cigarros: OS FILMES DE PEDRO COSTA, edited by Ricardo Matos Cabo, Lisboa: Orfeu Negro, 2009. — J.R.

The cinema of Pedro Costa is populated not so much by characters in the literary sense as by raw, human essences — souls, if you will. This is a trait he shares with other masters of portraiture, including Robert Bresson, Charlie Chaplin, Jacques Demy, Alexander Dovzhenko, Carl Dreyer, Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, and Jacques Tourneur. It’s not a religious predilection but rather a humanist, spiritual, and aesthetic tendency. What carries these mysterious souls, and us along with them, isn’t stories — though untold or partially told stories pervade all of Costa’s features. It’s fully realized moments, secular epiphanies.

Born in Lisbon in 1959, Costa grew up, by his own account, without much of a family. Speaking about O sangue, his first feature, he admitted that there was a personal aspect in his concentration on the incomplete family in that film “because I never really had a family. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 16, 2004). As much as I share my colleagues’ admiration [in 2012] for Jafar Panahi’s This is Not a Film, I must confess that I find it both depressing and somewhat insulting to Panahi that this is receiving more attention and praise in some quarters than his full-fledged films ever did, including such masterpieces as The White Balloon, The Circle, and Crimson Gold (not to mention Panahi’s more inventive and fruitful 2013 Closed Curtain, made under the same constraints as This is Not a Film). Which is why it seems worth reviving my review of the latter film. — J.R.

Crimson Gold **** (Masterpiece) Directed by Jafar Panahi Written by Abbas Kiarostami With Hussein Emadeddin, Kamyar Sheissi, Azita Rayeji, Shahram Vaziri, Ehsan Amani, and Pourang Nakhayi.

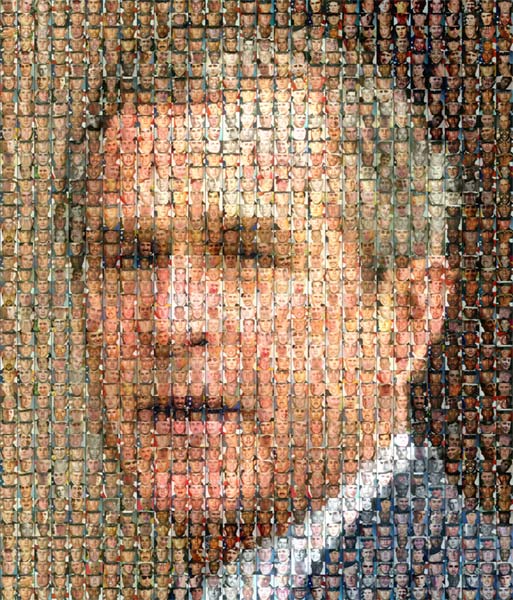

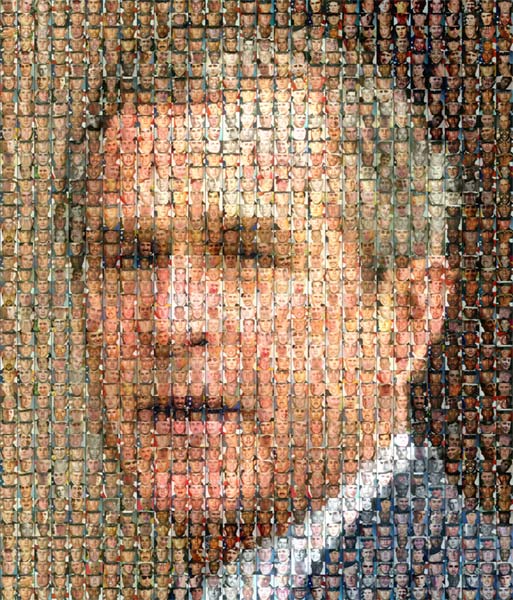

“War President” is an image. It is not a textual statement or rhetorical argument. An image is like an empty room and any message that one reads in that room necessarily came in the baggage one carried when one walked in the door. If I made an image of George Washington composed of images of the American dead from the revolution, would viewers likely take that image as an indictment of Washington? Read more

From the online Screening the Past, issue 36, posted 17 June 2013. — J.R.

Geoffrey Nowell-Smith and Christophe Dupin (ed.)

The British Film Institute, the Government and Film Culture, 1933-2000

Manchester/New York: Manchester University Press, 2012

ISBN: 978 0 7190 7908 5

US$95/UK£65

288pp (hc)

(Review copy supplied by Footprint Books/Warriewood)

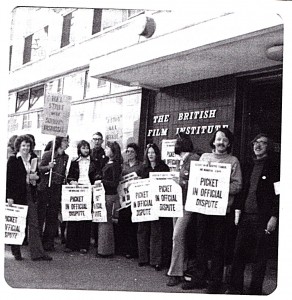

The most interesting job I’ve ever had was my two and a half years of working for the British Film Institute, between 1974 and 1977 –- as both assistant editor of the Monthly Film Bulletin (under Richard Combs) and staff writer for Sight and Sound (under Penelope Houston, who was directly responsible for my getting hired), occasioning at the time a move from Paris to London. This is what sparked my particular interest in this impressively detailed history, coedited and mostly written (apart from four of its 15 chapters) by the University of London’s Geoffrey Nowell-Smith and the International Federation of Film Archives’ Christophe Dupin after more than six years of research — and the fact that it retails for $95 at Amazon in the U.S. and 65 quid at Amazon in the U.K. meant that the only reasonable way I could acquire it was to ask to review it. Read more

The Spanish monthly film magazine that I write for, Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, invited me in the summer of 2019 to expand on my latest column for them as well as a few Facebook posts about Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Here is the result. — J.R.

Has 9/11 or the war on terror had any impact on you personally or creatively?

9/11 didn’t affect me, because there’s, like, a Hong Kong movie that came out called Purple Storm and it’s fantastic, a great action movie. And they work in a whole big thing in the plot that they blow up a giant skyscraper. It was done before 9/11, but the shot almost is a semi-duplicate shot of 9/11. I actually enjoyed inviting people over to watch the movie and not telling them about it. I shocked the shit out of them. But, again, I was almost thrilled by that naughty aspect of it. It made it all the more exciting.

But on some level you must have been caught up in the reality of 9/11.

I was scared, like everybody else. “OK, what is this new world we’re going to be living in? Is it going to be fucking Belfast here?” And I didn’t want to fucking fly nowhere. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1976. — J.R.

Prividenie, Kotoroe ne Vozvrashchaetsya

(The Ghost that Never Returns)

U.S.S.R., 1929

Director: Abram Room

In an unidentified South American country, José Real is serving a life sentence for having led an oilfield workers’ strike ten years earlier. After another prisoner breaks away from guards to tell him that the prison governor has a letter from his wife, and then leaps to his death, Real leads a revolt among the prisoners. The governor orders that they be sprayed with hoses; the revolt subsides, and Real is locked into a narrow cupboard. Conferring with the chief of the secret service, the governor recalls the regulation whereby a prisoner who has served ten years is entitled to one day’s liberty and decides to grant this to Real, with the understanding that he will be killed at the day’s end for trying to ‘escape’. After being shown his wife’s letter and hearing from a newly arrived prisoner that a new strike is planned at Hillside Well, Real agrees to go. Five days later – after news of his imminent arrival has reached his family, their neighbors and the oilfield workers — he sets out, warned that no one who has taken this leave has ever made it back alive. Read more

My Winter 2019 column for Cinema Scope. — J.R.

Some of Roman Polanski’s early features — Repulsion (1965), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Tess (1979) — are centred on vulnerable women, but as Bitter Moon (1992) makes abundantly clear, these are all films predicated on the male gaze, as are the more recent and more impersonal films of his that come closest to qualifying as Oscar bait (The Pianist [2002], arguably The Ghost Writer [2010], and, I would presume, An Officer and a Spy). Bitter Moon even problematizes this fact by assigning that gaze to two mainly unsympathetic males (Peter Coyote and Hugh Grant), and defining it mostly as poisonous, and Venus in Fur (2013) carries this tendency further by explicitly labelling it sexist, meanwhile making the male figure (Mathieu Almaric) almost a dead ringer for Polanski as a young man. Based on a True Story (2017), by focusing almost exclusively on two women (Emmanuelle Seigner and Eva Green), seeks to minimize the male gaze even more, not so much by problematizing it as by making it closer to irrelevant. Polanski himself comments on this fact in the interview included on the Spanish DVD of this film (apparently the only way it can be seen with English subtitles translating its French dialogue, which is how I finally managed to catch up with it). Read more

From the Summer 2019 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

Readers of Movie Mutations, the 2003 collection I co-edited with Adrian Martin, will know that the Jungian notion of global synchronicity has long been a preoccupation of mine. One striking recent manifestation of this phenomenon came to light when I read, around the same time, Mark Peranson’s editor’s note about Documentary Now! in the last issue of this magazine, and a ramble from David Thomson about binge-watching TV in the April Sight & Sound, both of which compelled me to finally take out a trial subscription to Netflix and spend the better part of a weekend binge-watching Series One and Two of Babylon Berlin (12 hours) and the even more absorbing Russian Doll(four hours) via streaming — just before receiving a four-disc PAL DVD box set of the former from Acorn Media International on Monday. All of which suggests that Mark, D.T., Acorn, and I have mysteriously been on roughly the same market wavelengths regardless of our illusions of free choice.

There’s a real danger that streaming may eventually make the name of this column anachronistic, so for the time being please allow me to include that viewing option, as I’ve already done with Blu-rays. Read more

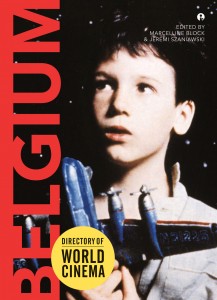

In today’s mail: Directory of World Cinema: Belgium, edited by Marcelline Block and Jeremi Szaniawski. Bristol, UK/Chicago, USA: Intellect Books, 332 pp., $31.95 from Amazon.

Discovered today on the Internet (at YouTube): 17 films by James Benning: five shorts (Two Cabins, Short Story, Two Faces, Postscript, Youtube) and a dozen features (Twenty Cigarettes, Ten Skies, One Way Boogie Woogie, Easy Rider, The War, Faces, After Warhol, Small Roads, Nightfall [see above photo], BNSF, casting a glance, Stemple Pass).

In both cases, untold riches. Just for starters, the book offers countless reviews and essays by 38 contributors exploring multiple facets of a neglected subject, the first detailed account I know in English of all the features of André Delvaux, fascinating interviews with Chantal Akerman and Boris Lehman (including the former’s description of The Misfits as “a documentary about Marilyn Monroe undergoing a depression” and the “extremely accurate, just relationship” between people and space in John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath), reflections on Jean-Claude Van Damme and “Belgium as Cinematic ‘Non-space’”. The Benning bounty includes five film that I’ve already seen and a dozen more that I haven’t . Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 24, 1993). — J.R.

LAST ACTION HERO

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John McTiernan

Written by Shane Black, David Arnott, Zak Penn, and Adam Leff

With Arnold Schwarzenegger, Austin O’Brien, Charles Dance, Anthony Quinn, Tom Noonan, Mercedes Ruehl, F. Murray Abraham, and Robert Prosky.

The word is out: Last Action Hero is an unmitigated disaster. The sound of studio panic was plainly audible in a report in the June 17 New York Times that Columbia Pictures threatened to sever all communications with the Los Angeles Times if it didn’t guarantee it would “never again run a story written or reported by Jeff Wells about (or even mentioning) this studio, its executives, or its movies.” Wells’s crime was a June 6 article in the Los Angeles Times reporting that a test-marketing preview of Last Action Hero held in Pasadena about two weeks earlier had been disappointing. The article contained “categorical denials” from several studio executives that such a screening had ever taken place, but clearly this wasn’t enough for the industry people. As Wells told the New York Times, “You’re talking about a studio in a major meltdown mode. These guys are blitzing out here.”

I read this story only hours before seeing another “disappointing” preview of Last Action Hero in Chicago, after several weeks of hearing rumors that the picture was a “mess” and in deep, deep trouble. Read more

This is my Introduction to The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S., a catalogue/ collection put together to accompany a film series at the Austrian Filmmuseum and the Viennale in Autumn 2009. — J.R.

I cannot tell a lie: the initial concept and impulse behind this retrospective weren’t my own. More precisely, they grew out of a series of email exchanges between myself and Hans Hurch and/or Alexander Horwath last April. Everything started when Hans proposed that I select a program devoted to American film comedy, “not as a history or anthology of the genre but in a more open and at the same time more concrete way…not [to] just dedicate it to comedy as such but to various aspects, different forms, ideas, and functions of the comic – from the earliest works of American cinema to recent films.”

Over three months later, I think it’s safe to say that I’ve fulfilled this proposal, at least if one can accept a fairly loose definition of “earliest” (i.e., 1919 –- which is already a good quarter of a century into what might be described as the history of American film, describing my own limitations better than the limits of my subject.) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 19, 1996). — J.R.

Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie 0 (no stars)

Directed by Jim Mallon

Written by Michael J. Nelson, Trace Beaulieu, Mallon, Kevin Murphy, Mary Jo Pehl, Paul Chaplin, and Bridget Jones

With Beaulieu, Nelson, Jeff Morrow, Rex Reason, Faith Domergue, and the voices of Mallon and Murphy.

The premise of the recently discontinued cable-TV series on which this film is based is more or less as follows: a blustering mad scientist named Dr. Clayton Forrester (Trace Beaulieu) plots to take over the world. His plan? According to the Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie press book: “Find the worst movies ever made, show them to the entire population and bring the planet to its knees.” He kidnaps Mike Nelson (Michael J. Nelson) to serve as a guinea pig, takes him to the Satellite of Love, and makes him and his three robot pals — Tom Servo, Gypsy, and Crow — watch the Worst Movies Ever Made. But Mike and his friends confound the experiment by talking back to the screen and making wisecracks. We watch the movies too — or parts of them, since the lower portion of the screen is partially blocked by the silhouettes of Mike and two of the robots. Read more