From the Chicago Reader (March 12, 2004). — J.R.

Secret Window

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by David Koepp

With Johnny Depp, John Turturro, Maria Bello, Timothy Hutton, Charles S. Dutton, and Len Cariou.

I’ve seen four movie adaptations of Stephen King books that have writers as heroes — The Shining (1980), Misery (1990), The Dark Half (1993), and now Secret Window — and I know of a few others. This isn’t necessarily self-indulgent on King’s part. An author this prolific would eventually run out of material if he didn’t use his own experience as a writer, and besides I happen to prefer the plotlines of The Shining and Misery to those of other King stories I know. He understands what it means to be a writer driven crazy by his own demons (in The Shining) as well as by some version of his public (in Misery), and even though he makes the heroes in both cases fairly dislikable, we wind up ensnarled in their dilemmas anyway. He also seems to have an astute take on writer’s block, suggesting that writing too much and repeating oneself can be as much a form of creative blockage as writing too little. Read more

Written for a tribute to Danièle Huillet in Undercurrent, on the FIPRESCI web site, in March 2006. — J.R.

One thing worth mentioning about Danièle: I’ve never known anyone who knew her and Jean-Marie well enough to know absolutely for sure whether or not they were literally husband and wife. This might strike some as a mere technicality, but I think it signifies something more. Whether they went through an actual wedding ceremony or wound up living together; whether they considered having children; whether it was inaccurate or precise, impolite or perfectly okay to refer to them as “the Straubs”: these are all basically questions about how they defined themselves in relation to society. And the fact that most of us don’t know the answers points towards a larger uncertainty about whether they were true bohemians or eccentric traditionalists (not necessarily the same thing), or some combination of the two. (Danièle only began to be credited as coauteur belatedly, after their first few films. But was this because she gradually became more active as a filmmaker or because the two of them began to place a higher value on her participation? Again, I have no idea.)

I think the fact that their work provokes silence more often than discussion — a tribute in some ways to its continuing radicality and difference — may be partly to blame for this. Read more

Written for and published in 10 To Watch: Ten Filmmakers for the Future, edited by Piers Handling and designed to accompany a program of films shown at the tenth anniversary of the Toronto Festival of Festivals in the fall of 1985. This was most likely the first time I attempted to write about Ruiz’s work at any length. –- J.R.

The sheer otherness of Raúl Ruiz in a North American context has a lot to do with the peculiarities of funding in European state-operated television that makes different kinds of work possible. The eccentric filmmaker in the U.S. or Canada who wants to make marginal films usually has to adopt the badge or shield of a school or genre — art film, avant-garde film, punk film, feminist film, documentary or academic theory film — in order to get funding at one end, distribution and promotion at another. Ruiz, on the other hand, needs only to accept the institutional framework of state television — which offers, as he puts it, holes to be filled — and he automatically acquires a commission and an audience without having to settle on any binding affiliation or label beyond the open-ended framework of “culture” or “education”. Read more

From the Spring 1984 issue of Sight and Sound. This was the first time I attended the film festival in Rotterdam and the first time I encountered the work of Raul Ruiz. It’s sadly emblematic that the Jancsó TV miniseries, even though it wound up being shown on the BBC, is so forgotten and out of reach today that I can’t even find a satisfactory still for it on the Internet. — J.R.

It’s a curious festival that can make young filmmakers like Henry Jaglom, Nicolas Roeg and John Sayles seem like commercial Hollywood directors. Devoted to the relatively unseeable and intractable independents across the globe whose work exists between the parentheses of an industry, Rotterdam has lasted for thirteen years, and under Hubert Bals’ inspired direction has this year added a market to amplify its already hefty fare. For an American who can hardly keep up with a Ruiz, Duras, Garrel or Jancsó without crossing the Atlantic, it was like stumbling into a forbidden forest of plenty, loaded with potential traps and unexpected rewards. Read more

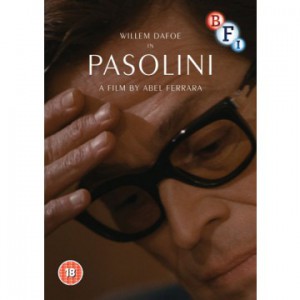

I can easily understand why some of Abel Ferrara’s biggest fans have certain reservations about his Pasolini (2014), available now on a splendid Region 2 Blu-ray from the BFI. Even if it’s a solid step forward from the stultifying silliness of Welcome to New York (2014), it lacks the crazed, demonic poetry of Bad Lieutenant (1992), The Addiction (1995), and New Rose Hotel (1998); most disconcertingly, it’s a responsible, apparently well-researched treatment of one of the most irresponsible of film artists, made by another film artist generally cherished for his own irresponsibility. And stylistically, it’s almost as if Ferrara has moved from being the great-grandson of F.W. Murnau to being the grandson of Vincente Minnelli—although one could argue, more precisely, that it isn’t really an auteur film at all. Yet as a portrait of the great and uncontainable Pier Paolo Pasolini, filtered through the last day of his life—a day focused on new creative work (a novel in progress and a film in pre-production) as well as various other activities, at home and on the street—it carries an undeniable conviction and emotional authenticity, which might make the prosaic strengths of Lust for Life (1956) a more useful model for Ferrara’s ambitions here than the poetic flourishes of a Faust (1926) or Tabu (1931). Read more

From the Spring 2012 issue of Cinema Scope. Some of the facts here may be out of date, so prospective customers should proceed with caution. — J.R.

The arrival on DVD of Jean-Pierre Gorin’s three solo features — Poto and Cabengo (1980), Routine Pleasures (1986), and My Crasy Life (1992) — has been long overdue, and it’s possible that part of the delay can be attributed to how unclassifiable and original these nonfiction films really are. The first of these has something to do with young twin sisters who were believed to have developed a private language between them, the second has something to do with both Manny Farber (as both a painter and a film critic) and a group of model train fans, and the third has something to do with the members of a Samoan street gang. But apart from Gorin’s presence and (quite diverse) Southern California settings, they’re very hard to describe or encapsulate, much less generalize about as a “trilogy” in any ordinary sense, which is part of their enduring fascination. (The same is true, mutatis mutandis, of Chris Marker’s Sans soleil [1982], which roams freely across the planet, already available with La jetée [1962] on a Criterion DVD and now out on a Criterion Blu-ray with the same materials — including terrific monologues by Gorin about both films that show how finely attuned he is to their special qualities, both as a friend of Marker and as a film essayist in his own right.) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 10. 2005). — J.R.

Cinderella Man

*** (A must see)

Directed by Ron Howard

Written by Cliff Hollingsworth and Akiva Goldman

With Russell Crowe, Renee Zellweger, Paul Giamatti, Craig Bierko, Paddy Considine, Bruce McGill, and Ron Canada

Ron Howard is an exemplar of honorable mediocrity. His films are conventional and stuffed with cliches, but their nice-guy liberalism is more sincere and nuanced than their tropes would lead one to expect. In his better efforts — Night Shift, Far and Away, Parenthood, The Paper, and now Cinderella Man — the sense of conviction is so passionate that the truth behind the cliches periodically emerges.

This is Howard’s first feature since the award-winning A Beautiful Mind, and the storytelling is fluid and gripping. He has plenty of cliches to peddle about boxing and working-class virtues in the midst of deprivation during the Depression, and the visual rhetoric in which he couches those cliches even give them a metaphysical dimension. The decor is as underlit as it is in Million Dollar Baby, and the cinematography’s even more mannerist in fetishizing darkness to project an aura of doom and desperation. In the deftly staged prizefight sequences, Howard goes even further than Clint Eastwood did in rendering subjective impressions in expressionistic terms. Read more

Reposted to mourn the death in 2015 of a titan, at age 106. From the July-August 2008 Film Comment, with the subhead “Negotiating the singular career of Portuguese master Manoel de Oliveira on the eve of his 100th birthday “. — J.R.

The cinema isn’t easy

Because life is complicated

And art indefinable.

Making life indefinable

And art

complicated.

— Manoel de Oliveira, “Cinematographic Poem,” 1986 (translated from the Portuguese)

Since this century has taught us, and continues to teach us, that human beings can learn to live under the most brutalized and theoretically intolerable conditions, it is not easy to grasp the extent of the, unfortunately accelerating, return to what our 19th-century ancestors would have called the standards of barbarism.

— Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1991

To insist that all great filmmakers contain multitudes is to risk a counter-response — that the same might equally be said of the not-so-great. Just as much labor can be expended on bad work as on good, and this applies to the labor of viewers and filmmakers alike. Read more

This is the pre-edited version of a review published in its post-edited form elsewhere on this web site, as well as in the March 25, 2005 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

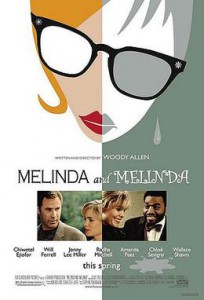

MELINDA AND MELINDA*

DIRECTED AND WRITTEN BY WOODY ALLEN WITH RADHA MITCHELL, WILL FERRELL, CHLOE SEVIGNY, CHIWETEL EJIOFOR, JONNY LEE MILLER, BROOKE SMITH, WALLACE SHAWN, AND LARRY PINE

“Amongst a democratic population, all the intellectual faculties of the workman are directed to…two objects: he strives to invent methods which may enable him not only to work better, but quicker and cheaper; or, if he cannot succeed in that, to diminish the intrinsic quality of the thing he makes, without rendering it wholly unfit for the use for which it is intended. When none but the wealthy had watches, they were almost all very good ones; few are now made which are worth much, but everybody has one in his pocket. Thus the democratic principle not only tends to direct the mind to the useful arts, but it induces the artisan to produce with great rapidity many imperfect commodities, and the consumer to content himself with these commodities.”

— Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (1835)

De Tocqueville’s 170-year-old account of why Americans often blanch at intellectual abstraction and art-for-art’s-sake — and prefer accessibility over complexity when it comes to both thought and art — still seems pretty up to date. Read more

From the November 25, 2005 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Although this 1960 movie is usually accorded a low place in the Marilyn Monroe canon — understandably so, because the comedy and musical numbers never quite take off the way they’re supposed to, and the central plot premise is more than a little labored — it deserves to be reevaluated for the intelligence of Monroe’s performance and the rare independence of her character; this one was made after her brush with Actors Studio, and she isn’t playing a bimbo. Yves Montand costars as a reclusive billionaire who discovers he’s being parodied in an off-Broadway revue; he tries out for the part himself, incognito, and she’s the chorus girl who helps him along. George Cukor directed, in ‘Scope, and lent a certain glamour and polish to the proceedings. With Tony Randall, Wilfrid Hyde-White, Frankie Vaughan (whose number, “Incurably Romantic,” isn’t half-bad), and bits by Milton Berle, Bing Crosby, and Gene Kelly; Norman Krasna wrote the querulous script. 118 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

My DVD column in Cinema Scope 44, Fall 2010. — J.R.

1. A confession

Since retiring from my job as a weekly reviewer in early 2008, I’ve been discovering that I usually prefer watching mediocre films of the past (chiefly from the 30s through the 70s) to watching mediocre films of the present — unlike some of my former readers, who irrationally conclude that I’ve stopped writing about movies because I no longer work for the studio airheads in implementing their latest ad campaigns. That is, I no longer train most of my attention on contemporary industry releases, as I was obliged to do for the preceding 20 years, because, in keeping with Raymond Durgnat’s apt observation that dated films sometimes have more to teach us than “timeless” classics, I’m looking for stuff I can chew on. (Try to imagine what literary criticism would be like if most or all of its practitioners decided that 2010 publications currently on sale at K-Mart comprised the bulk of all the literature ever published that was worthy of our close attention.)

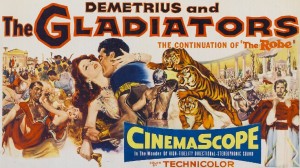

This is why, for instance, I wound up picking up a copy of Delmer Daves and Philip Dunne’s sequel to The Robe, Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954), at a video store in Córdoba, Argentina in late July (although, as I later discovered, I could have picked it up on Amazon for roughly the same price): not because it’s any sort of masterpiece (though it’s probably a better movie than The Robe), but because I find it interesting from multiple vantage points, e.g., Read more

From the January 19, 2006 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Cafe Lumiere

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien

Written by Hou and Chu T’ien-wen

With Yo Hitoto, Tadanobu Asano, Masato Hagiwara, Kimiko Yo, and Nenji Kobayashi

Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World

*** (A must see)

Directed and written by Albert Brooks

With Brooks, Sheetal Sheth, John Carroll Lynch, Jon Tenney, and Fred Dalton Thompson

“It’s very difficult to cross national borders and shoot a film about a different culture. How many films have you seen that do that successfully? There are very few. The reason is very simple. When we look at films [about our own country] made by foreign companies, they’re not accurate. . . . But it’s an interesting challenge.”

This could be Albert Brooks talking about the making of his funny new feature, Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World, most of it filmed in New Delhi. But it’s actually Taiwanese master Hou Hsiao-hsien speaking about Cafe Lumiere, which was shot in Japan. Both filmmakers are pushing 60, and both prefer filming in long shot and extended takes. And both their movies are acute, measured observations of contemporary life and thought, whether we happen to be based in LA or Tokyo. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 5, 2005). — J.R.

Saraband

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Ingmar Bergman

With Liv Ullmann, Erland Josephon, Borje Ahlstedt, Julia Dufvenius, and Gunnel Fred

Broken Flowers

*** (A must see)

Directed and written by Jim Jarmusch

With Bill Murray, Julie Delpy, Jeffrey Wright, Sharon Stone, Alexis Dziena, Frances Conroy, Christopher McDonald, Chloe Svigny, Jessica Lange, Tilda Swinton, and Mark Webber

Ingmar Bergman’s Saraband and Jim Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers are two minimalist features about burned-out individuals picking over the wreckage of relationships they can barely remember and about the special art of not really giving a shit. (A third is Gus Van Sant’s Last Days, scheduled to open here next week.) With its sprawling and far from symmetrical plot, Saraband, made in 2003 for Swedish television, is stark and economical, with a small cast of characters and sparse rural settings, and it seems like an apocalyptic endgame in terms of Bergman’s own career — the end of the world as he knows it. It was shot in digital video, and at Bergman’s insistence is being projected as such — and his peculiar use of that medium is what makes this work compelling.

I wouldn’t dream of contesting Bergman’s status as a film master. Read more

From the November 4, 2005 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

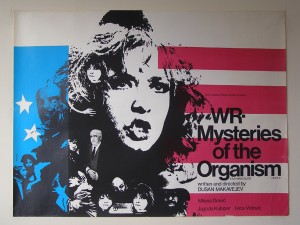

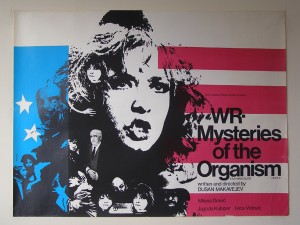

We may forget that the most radical rethinking of Marx and Freud found in European cinema of the late 60s and early 70s came from the east rather than the west. Indeed, it’s hard to think of a headier mix of fiction and nonfiction, or sex and politics, than this brilliant 1971 Yugoslav feature by Dusan Makavejev, which juxtaposes a bold Serbian narrative shot in 35-millimeter with funky New York street theater and documentary shot in 16. The WR is controversial sexual theorist Wilhelm Reich and the mysteries involve Joseph Stalin as an erotic figure in propaganda movies, Tuli Kupferberg of the Fugs killing for peace as he runs around New York City with a phony gun, and drag queen Jackie Curtis and plaster caster Nancy Godfrey pursuing their own versions of sexual freedom. In English and subtitled Serbo-Croatian. NC-17, 85 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

What dispiriting news, to learn of Raúl Ruiz’s death at age 70 upon waking today [in August 2011], just after receiving the Portuguese DVD box set of his extraordinary Mysteries of Lisbon yesterday and watching the first half of it last night. I knew, of course, that his health had been very poor, so this wasn’t entirely a shock. But it’s clearly a major loss. (A curious coincidence: Raúl lived the same number of years as the filmmaker he admired the most, Orson Welles.)

We had been friends for a time, then drew apart — mainly, I suspect, because he became a little fed up with my inability to speak and understand French more fluently. But I’m very grateful for the many hours we were able to spend together, including one opportunity I had to appreciate what an excellent cook he was. (For an excellent memoir about him, as well as one of the best appreciations of Ruiz that I know — even though I disagree with its premise that Klimt qualifies as a biopic [at least in its original, longer, and better version], and Raúl himself disagreed with the premise that Three Lives and Only One Death was one of his best films — check out Adrian Martin’s “A Ghost at Noon” at http://www.filmcritic.com.au/essays/ruiz.html.)

Read more