Written for The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S., a catalogue/collection put together to accompany a film series at the Austrian Filmmuseum and the Viennale in Autumn 2009. — J.R.

The brassy and obnoxious show-biz type that

Albert Brooks plays in his first and funniest feature

(1979) –- so close to Brooks’s own public persona that

he’s called Albert Brooks –- professes to be impervious

to all the self-consciousness that engulfs him.

Even when he’s shooting an extended documentary

about the life of a “typical” family in Phoenix,

Arizona in the style of the infamous 1973 cinéma-

vérité TV series An American Family, he claims

that anything the family does in front of the camera is

“right,” without ever admitting that the acute self-consciousness

created by his film and camera crew

ultimately has more to do with movies than with real

life. Charles Grodin brilliantly plays the animal

doctor at the head of this family, and Brooks is so

skillful at juggling all the mannerisms of pseudo-documentary

and all the specious claims of pop psychology

that his periodic and compulsive regressions to

old-time show business -– whether it’s the big-time

pop vocal in the opening sequence or the conflagration

inspired by Gone with the Wind at the

end –- manage to be both welcome and ludicrous. Read more

From Film Comment (January-February 1982); reprinted in my book Film: The Front Line 1983. My thanks to Jon Jost himself for furnishing me with the frame grabs from Last Chants for a Slow Dance and Stagefright. — J.R.

1. “This is a movie, a way to speak. It is bound, like all systems of communication, with conventions. Some of these are arbitrarily imposed, some are imposed by economic or political pressures, some are imposed by the medium itself. Some of these conventions are necessary: They are the commonality through which we are able to speak with one another in this way. But some of these conventions are unnecessary, and not only that, they are damaging to us, they are self-destructive. Yet we are in a bad place to see this. We are in a theater.” Jon Jost, addressing the camera and spectator in Speaking Directly (1974).

2. Despite five substantial and in many ways remarkable features under his belt since 1974, and nineteen shorts since 1963, Jon Jost at 38 is still a long way from becoming even an arcane household name in this country. Not that he makes it easy on anyone. His originality, technical virtuosity, and political sophistication have all tended to work against him by showing the rest of us up — thereby banishing him from most of the restricted genre and market classifications designed to protect us from his scorn, under avant-garde and mainstream umbrellas alike. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 5, 1996). — J.R.

The Neon Bible

Directed and written by Terence Davies

With Gena Rowlands, Diana Scarwid, Jacob Tierney, Denis Leary, Leo Burmester, Frances Conroy, and Peter McRobbie.

Two paradoxical facts about Terence Davies’s first film adaptation:

(1) It follows fairly closely The Neon Bible, a novel written by John Kennedy Toole for a literary contest in the mid-50s, when he was 16 — a decade before he finished work on his second novel, A Confederacy of Dunces, and about 15 years before he, still unpublished, committed suicide (A Confederacy of Dunces was published ten years later, The Neon Bible ten years after that). I don’t care much for The Neon Bible, a hackneyed mood piece set in a rural backwater of the deep south, but I think the movie, which seems 100 percent Davies, is wonderful.

(2) Of all the English-speaking films shown at Cannes last May, the two that got the most boorish and least comprehending reception by the English-speaking press were The Neon Bible and Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, though for nearly opposite reasons. Jarmusch, who’s long been criticized for coasting along in Down by Law, Mystery Train, and Night on Earth on the same kind of hip humor he virtually invented for Stranger Than Paradise, finally broke free and did something bold, original, political, dark, scary, outspoken, witty, and often beautiful — a black-and-white western that should be opening here sometime next month. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 21, 1994). This is also reprinted in my collection Movies as Politics. — J.R.

*** ED WOOD

(A must-see)

Directed by Tim Burton

Written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski

With Johnny Depp, Martin Landau, Sarah Jessica Parker, Patricia Arquette, Jeffrey Jones, Bill Murray, Lisa Marie, George “The Animal” Steele, and Vincent D’Onofrio.

*** PULP FICTION

(A must-see)

Directed and written by Quentin Tarantino

With John Travolta, Samuel L. Jackson, Uma Thurman, Bruce Willis, Ving Rhames, Maria de Medeiros, Tim Roth, Amanda Plummer, Harvey Keitel, Eric Stoltz, Rosanna Arquette, Christopher Walken, and Tarantino.

[The media] ask those who know nothing to represent the ignorance of the public and, in so doing, to legitimize it.

— Serge Daney, Sight and Sound

If you want a happy ending, that depends, of course, on where you stop your story. — Orson Welles

In Vamps & Tramps, Camille Paglia’s latest collection of sound bites and press clips, one finds an extended account of her long-term obsession with Susan Sontag, including the following nugget: “She is literally being passed by a younger rival, and she’s not handling it, I’m afraid, very gracefully. . . . I am the Sontag of the 90s, there’s no doubt of it.” Read more

Commissioned by Found Footage for its 4th issue (February 2018). — J.R.

We’re living through a confusing transitional period whose transitions are chiefly matters of financial speculation lying beyond our control. Theorizing our helpless condition — which often means attempting to rationalize it, or to adapt to it by other means — we’re obliged to use an out-of-date language. This antiquated language needs to be upgraded with a new vocabulary if we want to make useful sense of what’s happening — something that we haven’t yet figured out how to do. Just as “politically correct” language can sometimes be described as the language of defeat – struggling to make an adequate representation of a reality over which one has lost control – theoretical cinema suggests at times a farewell gesture towards a medium that has fled.

The fumblings to be found below are an attempt to clarify not so much five experimental films in 35-millimeter and CinemaScope by Peter Tscherkassky — L’Arrivée (1997-1999, 2:09 min.), Outer Space (1999, 9:58 min.), Get Ready (1999, 1:06 min.), Dream Work (2001,11 min.), and Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine (2005, 17 min.), all of which I find powerful, provocative, haunting, and ultimately confounding — as the confusing language used to describe them. Read more

These are the original letters published in French translation in Trafic no. 24, Winter 1997 and subsequently published in English in a 2003 book edited by Adrian Martin and myself, Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (London: British Film Institute). These letters have by now also appeared in Croatian, Dutch, Farsi, French, German, and Spanish. — J.R.

From Jonathan Rosenbaum (Chicago):

7 April, 1997

Dear Adrian,

Almost a year has passed since I wrote in Trafic* about “the taste of a particular generation of cinephiles — an international and mainly unconscious cabal (or, more precisely, confluence) of critics, teachers, and programmers, all of whom were born around 1960, have a particular passion for research (bibliographic as well as cinematic), and (here is what may be most distinctive about them) a fascination with the physicality of actors tied to a special interest in the films of John Cassavetes and Philippe Garrel (as well as Jacques Rivette and Maurice Pialat).” I named four members of this generation — Nicole Brenez (France), Alexander Horwath (Austria), Kent Jones (U.S.), and you (Australia). Each of you, I should add, I met independently of the other three, originally through correspondence (apart from Kent), although Kent and Alex already knew each other. Read more

The following was written for CITIZEN PETER, a very handsomely produced and multilingual 476-page book celebrating the late Peter von Bagh’s 70th birthday, in late August 2013, coedited by Antti Alanen and Olaf Möller. — J.R.

Preface

Peter von Bagh is the man who convinced me to purchase my first multiregional VCR in the early 1980s. So he has a lot to answer for — including, just for starters, my DVD column in Cinema Scope.

We’ve met at various times in Paris, London, New York, Southern California, Chicago, Helsinki, Sodankylä, and Bologna — and probably in other places as well, although these are the ones I currently remember. The first times were in Paris in the early 1970s, when he looked me up, and it must have been either in San Diego in 1977 or 1978 or in Santa Barbara between 1983 and 1987 that he convinced me to buy a multiregional VCR. Most likely it was the latter, where I was mainly bored out of my wits apart from my pastime of taping movies from cable TV, and Peter maintained that if we started swapping films through the mail, a multiregional VCR would allow me to play some of the treasures he could send me. Read more

From Take One (January 1979). — J.R.

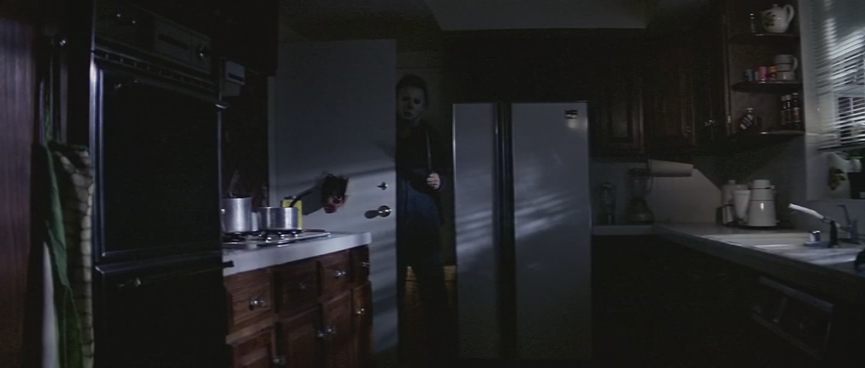

In order to do justice to the mesmerizing effectiveness of Halloween, a couple of mini-backgrounds need to be sketched: that of writer-director John Carpenter, and that of the Mainstream Simulated Snuff Movie — a popular puritanical genre that I’ll call thw MSSM for short.

(1) On the basis of his first two low-budget features, it was already apparent that the aptly-named Carpenter was one of the sharpest Hollywood craftsmen to have come along in ages — a nimble jack-of-all-trades who composed his own music, doubled as producer (Dark Star) and editor (Assault on Precinct 13), and served up his genre materials with an unmistakably personal verve. Both films deserve the status of sleepers; yet oddly enough, most North American critics appear to have slept through them, or else stayed away. Somehow, the word never got out, apart from grapevine bulletins along a few film-freak circuits.

Dark Star proved that Carpenter could be quirky and funny; Assault showed that he could be quirky, funnu, and suspenseful all at once. Halloween drops the comedy, substitutes horror, and keeps you glued to your seat with ruthless efficiency from the first frame to the last. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 7, 1996). — J.R.

Mission: Impossible

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Brian De Palma

Written by David Koepp, Steven Zaillian, and Robert Towne

With Tom Cruise, Jon Voight, Henry Czerny, Emmanuelle Beart, Jean Reno, Ving Rhames, Kristin Scott-Thomas, and Vanessa Redgrave.

The Phantom

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Simon Wincer

Written by Jeffrey Boam

With Billy Zane, Kristy Swanson, Treat Williams, Catherine Zeta Jones, James Remar, and Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa.

My Favorite Season

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Andre Téchiné

Written by Téchiné and Pascal Bonitzer

With Catherine Deneuve, Daniel Auteuil, Marthe Villalonga, Jean-Pierre Bouvier, Chiara Mastroianni, Carmen Chaplin, Anthony Prada, and Michèle Moretti.

I think that one never grows up emotionally. We grow up physically, intellectually, socially, and even morally but never emotionally. Recognition of this fact can be either terrifying or deeply moving. Everyone handles it in their own way. — Andre Téchiné

The principal pleasure of the Cannes festival for me was a two-week vacation from the “fun” of American movies. Maybe this fun — which points to our inability to grow up emotionally — would seem less oppressive if it didn’t also inform the American experience of news, politics, fast food, sports, economics, education, religion, and leisure in general; this kind of fun is less an escape than an enforced activity, a veritable civic duty. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 31, 1992). — J.R.

![]()

DEATH BECOMES HER

No stars (Worthless)

Directed by Robert Zemeckis

Written by Martin Donovan and David Koepp

With Goldie Hawn, Meryl Streep, Bruce Willis, Isabella Rossellini, Ian Ogilvy, Adam Storke, and Sydney Pollack.

“The copper is fair game for pies, likewise any fat man. Fat faces and pies seem to have a peculiar affinity. If the victim is fat enough the movie public will tolerate any kind of rough stuff.

“On the other hand, movie fans do not like to see pretty girls smeared up with pastry. Shetland ponies and pretty girls are immune.

“It is an axiom of screen comedy that a Shetland pony must never be put in an undignified position. People don’t like it. You can take any kind of liberties with a donkey. They even like to see the noble lion rough-housed, but not a pony. You might as well show Santa Claus being mistreated.

“The immunity of pretty girls doesn’t go quite as far as the immunity of the Shetland pony, however. You can put a pretty girl in a comedy shower bath. You can have her fall into mud puddles. They will laugh at that. But the spectacle of a girl dripping with pie is displeasing. Read more

I wrote this book review for The Village Voice shortly after I moved to London from Paris in 1974 (which helps to explain how I could cite the English paperback of Myra Breckinridge), so I was more than likely a little miffed when the Voice noted at the end of the piece, “Jonathan Rosenbaum is a film critic presently living in Paris.” Although I think this review suffers a bit from the Voice‘s overheated smart-alecky manner during this period, which I was only too willing to adopt (and which makes some of my gripes potentially open to the charge of the pot calling the kettle black), I was reminded of both this review and Myra Breckinridge/Myron while recently reading Vidal’s somewhat similar 1978 novel Kalki, which has a similarly formidable heroine-narrator with a comparably ambiguous relation to gender. — J.R. [4/3/09]

More Vidal

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

_____________________________________________________

Myron

Gore Vidal

Random House, $6.95

______________________________________________________

Myra Breckenridge was a stunt: a clever gay trick pulled on a straight audience — or, if one prefers, a bisexual prank pulled on a unisexual audience — with kibitzers and spectators welcome on either side of the ironies, different jokes for different folks. Read more

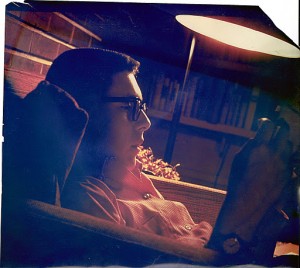

This piece by Ehsan for Fandor’s Keyframe originally appeared on the day before my 70th birthday (February 26, 2013).– J.R.

Jonathan Rosenbaum at 15, imagination in the process of being liberated.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, at the cusp of seventy, talks about a life of jazz and cinema.

By Ehsan Khoshbakht February 26, 2013

The needs-no-introduction film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum turns seventy this month, but that does not mean that he has grown out of touch. His latest book, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia (University Of Chicago Press, 2010), displays Rosenbaum’s engagement with digital-era realities, and manages something few if any critics of his generation are capable of in the current environment: optimism. Self-catalogued on his own website, the critic’s life of writing, from his late teens to the two-thousand-and-teens, coheres, and the collection of work is unmatched by any living film writer for its breadth and rigor. A closer look at his contribution to film literature (with featured articles in the weightiest of magazines and translations of his baker’s dozen books into languages as diverse as Chinese and Farsi) finds Rosenbaum generally bringing a sense of urgency to his subjects, no matter the decade.

My rather personal ties with the Chicago-based critic comes from our mutual love of jazz, which, aside from its ecstatic pleasures (that sometimes surpasses cinema’s), can assist writers in the ways they approach any other art form. Read more

From the May 20, 1988 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

BABETTE’S FEAST

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Gabriel Axel

With Stephane Audran, Jean-Philippe Lafont, Gudmar Wivesson, Jarl Kulle, Hanne Stensgard, Bodil Kjer, Vibeke Hastrup, and Birgitte Federspiel.

Only when she had lost what had constituted her life, her home in Africa and her lover, when she had returned home to Rungstedlund a complete “failure” with nothing in her hands except grief and sorrow and memories, did she be come the artist and the “success” she never would have become otherwise — “God loves a joke,” and divine jokes, as the Greeks knew so well, are often cruel ones. What she then did was unique in contemporary literature though it could be matched by certain nineteenth century writers — Heinrich Kleist’s anecdotes and short stories and some tales of Johann Peter Hebel, especially Unverhofftes Wiedersehen come to mind. Eudora Welty has defined it definitively in one short sentence of utter precision: “Of a story she made an essence; of the essence she made an elixir; and of the elixir she began once more to compound the story.” — Hannah Arendt on Isak Dinesen

When Ernest Hemingway accepted his Nobel prize in 1954, he was gracious enough to acknowledge that it should have gone to Isak Dinesen instead. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 24, 1997). — J.R.

Chantal Akerman by Chantal Akerman

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Chantal Akerman.

This weekend the Museum of Contemporary Art, as part of its exhibit “Hall of Mirrors: Art and Film Since 1945,” is presenting not only Chantal Akerman, one of the finest filmmakers working anywhere, but also the two features I would describe as her greatest achievements — the 200-minute narrative Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) and the 107-minute documentary From the East (D’est, 1993). To make the program even more fully rounded, the museum is also showing a 64-minute self-portrait, Chantal Akerman by Chantal Akerman (1996), which provides an excellent introduction to her work as a whole. (This film and Akerman herself will appear on Sunday; From the East shows on Friday, and Jeanne Dielman on Saturday.)

Despite her significant and still growing international reputation, Akerman isn’t yet considered an “established” mainstream or avant-garde artist, because many critics in both spheres still treat her as something of an interloper, even an irritation or a threat. A friend who’s a highly respected novelist and film critic recently told me that he regards all her work as worthless, even though he hasn’t bothered to look at all of it. Read more

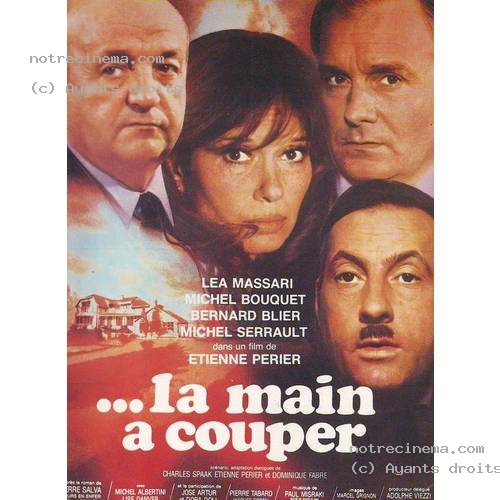

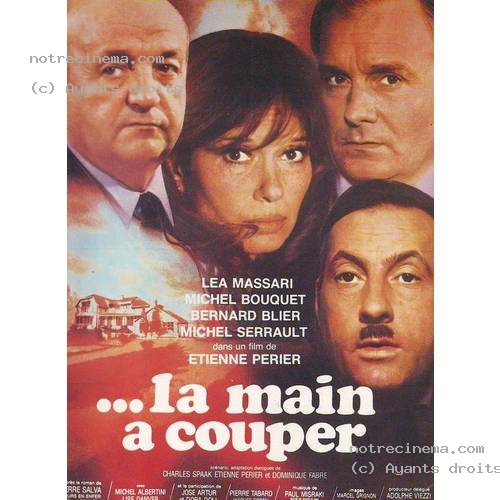

From Oui (August 1974). — J.R.

La main à couper. It’s been suggested that one reason why movies are so popular in Paris is that French TV is so bad. In point of fact,a conventional Gallic thriller such as the current La main à couper is not very different from what an American spectator is likely to see in a weekly series like Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The central intrigue, of course, is classically Continental: bourgeois adultery, the same subject that Claude Chabrol staked out years ago, although it is as perpetually common to French melodrama as raincoats are to spy thrillers. A married woman (Lea Massari) is having an affair with a young sculptor who is roughly the same age as her son. One day she goes to meet him at his studio and finds him dead, murdered with a blunt instrument. From this point on, practically all of the suspense and tensions develop out of the hypocrisy that her position requires, She can’t go to the police or tell her husband (Michel Bouquet), her daughter, or her son. The task of behaving normally becomes even more of an ordeal when an odd little fellow with a Hitler mustache (Michel Serrault) turns up and starts blackmailing her.This, Read more