Written originally for Trafic no. 12 (Fall 1994), where it appeared in French translation, translated by Bernard Eisenschitz; all three letters first appeared in English in Persistence of Vision No,. 11, 1995. — J.R.

June 13, 1994

Dear Bill,

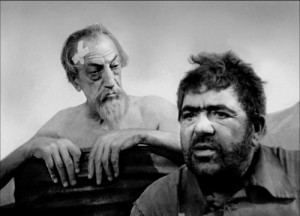

It’s good to have all your multifaceted thoughts about It’s All True, which makes your letter worth the long wait. I especially value what you have to say regarding the political implications of the film in the 1940s as well as the 1990s, because it seems that those implications have mainly eluded critics in both decades. As you well know, it wasn’t until Robert Stam published “Orson Welles, Brazil, and the Power of Blackness” in the seventh issue of Persistence of Vision (1989), with corroborating essays by both Catherine and Susan Ryan, that it finally became clear, forty-odd years after the event, that part of what was rattling so many studio executives and Brazilian government officials alike about Welles’s behavior in Rio was his particular interest in blacks. Maybe you’re right that he wasn’t a radical, but if It’s All True had been completed and released in the early 1940s, it still might have offered a radical precedent: three Latin American stories focusing on non-white heroes. Read more

Written originally for Trafic no. 12 (Fall 1994), where it appeared in French translation, translated by Bernard Eisenschitz; all three letters first appeared in English in Persistence of Vision No,. 11, 1995. — J.R.

June 7, 1994

Dear Jonathan,

Sorry to have been so long replying. As you say, much has happened since you wrote your letter. We both started out years ago in a series of polemical articles to correct received ideas of Welles, and we seem to be making progress. This Is Orson Welles and It’s All True will be more widely read and seen than those articles ever were. Already Richard Combs, writing about f for fake in the January–February 1994 Film Comment, acknowledges the thesis of Welles the independent filmmaker advanced by you in “The Invisible Orson Welles” as a corrective to the idea of Welles the great failure, then proceeds to propose a new theory of the work, with failure of another kind inscribed in it from the start. That article would have been unthinkable a few years ago, when what might be called the vulgar theory of failure was still dominant.

The work on the Welles legacy is going well: Oja is set to co-direct a documentary that will include several of the important fragments; The Deep and The Other Side of the Wind may be finished in the next couple of years, and hope springs eternal where The Merchant of Venice is concerned. Read more

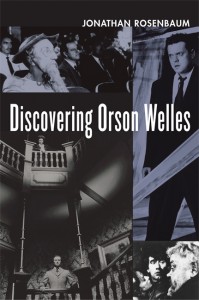

Written originally for Trafic no. 12 (Fall 1994), where it appeared in French translation, translated by Bernard Eisenschitz; all three letters first appeared in English in Persistence of Vision No,. 11, 1995. The version here, including my introduction, comes from Discovering Orson Welles. — J.R.

This chapter -— the longest in my 2007 book Discovering Orson Welles, and in some ways my favorite -— was originally written for the French quarterly Trafic, and in fact was the first thing I ever wrote specifically for that magazine. The late Serge Daney (1942–1994) —- whom I’d known since his stint as editor of Cahiers du cinéma, when he’d gotten me to serve briefly as its New York correspondent (after Bill Krohn had shifted from that post to the same magazine’s Los Angeles correspondent) -— died of AIDS not longer after launching Trafic, and by my own choice, my first contribution, a memoir about working for Jacques Tati (see “The Death of Hulot” in my collection Placing Movies), was something I’d already written for and published in Sight and Sound. My second contribution was my brief introduction to Orson Welles’s “Memo to Universal”, an “outtake” from This Is Orson Welles that had been accepted by Serge’s coeditors (Raymond Bellour, Jean-Claude Biette, Sylvie Pierre, and Patrice Rollet) during Serge’s illness. Read more

From Sight and Sound (June 2011). Portabella continues to be the most flagrantly unseen and overlooked of major contemporary filmmakers, for reasons suggested in this sketch. — J.R.

Jonathan Rosenbaum voyages into the elusive and intriguing worlds created by Spanish filmmaker Pere Portabella

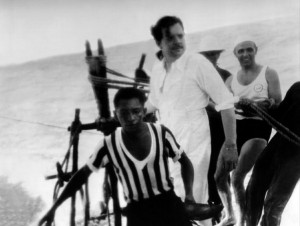

Among the lost continents of cinema — major films and artists that have perpetually eluded our grasp because they fall outside the usual institutional frameworks that we depend upon to ‘keep up’ with cinema — there are few contemporary figures more neglected than Catalan filmmaker Pere Portabella.

Born into a family of industrialists in Barcelona in 1929, Portabella has remained closely tied to that city’s art scene for most of his life, especially as a patron and friend of other Catalan artists. One of these was Joan Miró, the focus of a major retrospective at the Tate Modern this summer and the subject of five of Portabella’s shorter fiIms from the late 1960s and early 70s. (The two I’m most familiar with are Miró L’Altre, chronicling the artist’s painting and subsequent erasing of a mural at the Colegio de Arquitectos de Catalunya, and Miró 37/Aidez L’Espagne, which similarly explores a ‘making’ and ‘unmaking’, this time of Spain itself during the mid-1930s, via newsreel footage.) Read more

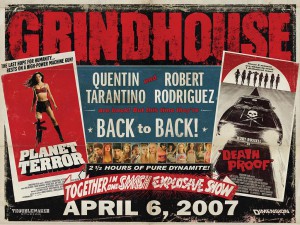

From the Chicago Reader (April 6, 2007). — J.R.

Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez’s celebration of 70s-style sleaze, 191 minutes long including a short intermission, seems ideally suited for gleeful, mean-spirited 11-year-old boys who can sneak into this double bill despite the R rating. I enjoyed the invented trailers the directors fold into the mix, but despite the jokey missing reels, these two full-length features are each 20 minutes longer than they need to be, and neither one makes much sense as narrative. Rodriguez’s Planet Terror is virtually nothing but gross-out gags involving castration, dismemberment, mass murder, zombies, and Osama bin Laden. Tarantino’s Death Proof starts off as a meandering look at Austin’s Tex-Mex joints — there’s more gab here than in any of his work since Reservoir Dogs — then gravitates into a blend of Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, and stunt-driving movies, culminating in some well-filmed action and more celebratory killing. (Making us feel good about enjoying gory mayhem — or in my case, at least trying to do that — has always been his specialty.) With Rose McGowan, Freddy Rodriguez, Josh Brolin, Kurt Russell, Rosario Dawson, and Zoe Bell. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From Cineaste, Summer 2007. — J.R.

Walt Disney:

The Triumph of the American Imagination

by Neal Gabler. New York:

Alfred A. Knopf, 2006. 851 pp.,

illus. Hardcover: $35.00.

This is the first book by Neal Gabler since his magisterial and eye-opening An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood (1988) that hasn’t seriously disappointed me, though I didn’t warm to its virtues right away. His 1994 biography of Walter Winchell (Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity) had less of an impact on me than the 1971 journeyman’s effort of Bob Thomas (which I also preferred to Michael Herr’s 1990 musings on the subject), while Life, The Movie: How Entertainment Conquered Reality (1998), which I barely remember now, felt at the time like all windup and no delivery. And one clear limitation of this hefty volume from the outset, in spite of its strengths, is that Gabler can’t function very effectively as either a critic of Disney’s films or as a historian of Hollywood animation; his talent lies elsewhere.

Given Gabler’s privileged access to Disney files and papers, this may be the closest thing to an authorized biography that we can expect to get, but it doesn’t exactly add up to an apologia — even though it refutes charges of Disney being anti-Semitic, and, apart from occasionally conceding that he was mainly a passionately anti-union Goldwater Republican, tends to depoliticize him. Read more

Age is… Re:Voir Video

Army Criterion Eclipse

Jauja Cinema Guild

Letter from Siberia (Blu-ray included in the Chris Marker Collection) Soda Film + Art

Moana with Sound Kino Lorber

Despite (or is it because of?) the disorderly quirks of commerce, ideology, and opportunity, we all occupy disparate time frames, so I’ve unapologetically cited, in alphabetical order, five imperishable films that I happened to encounter for the first time in 2015, all of them in digital editions worthy of their achievements.

Dwoskin’s last film – a satisfying conclusion to a remarkable career – comes from the same label that afforded me my first look at Marcel Hanoun’s remarkable 1966 L’authentique procés de Carl-Emmanuel Jung with English subtitles.

Army is a wartime propaganda feature subverted into a pacifist lament, Jauja a haunting medieval western (or southern) time-bent into a luscious advance in Alonso’s art.

Letter from Siberia, even without the benefit of the French version promised on its jacket, is a delightful early essay film showing its author’s wit, literary gifts, and photojournalistic richness in optimal form, enhanced by a superb Roger Tailleur essay.

And Moana with sound is a seemingly unpromising but beautifully realized re-edition and further enrichment of the Flahertys’ early masterpiece, launched by their daughter Monica and restored by their great-grandson Sami van Ingen and Bruce Posner. Read more

Here are three of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007). Each one of these entries devoted to “scenes” has something to do with imaginatively combining animation with live-action. — J.R.

***

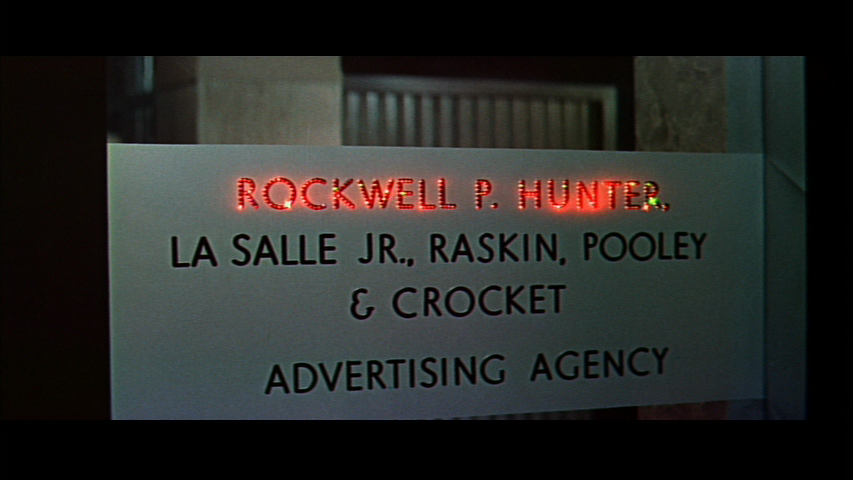

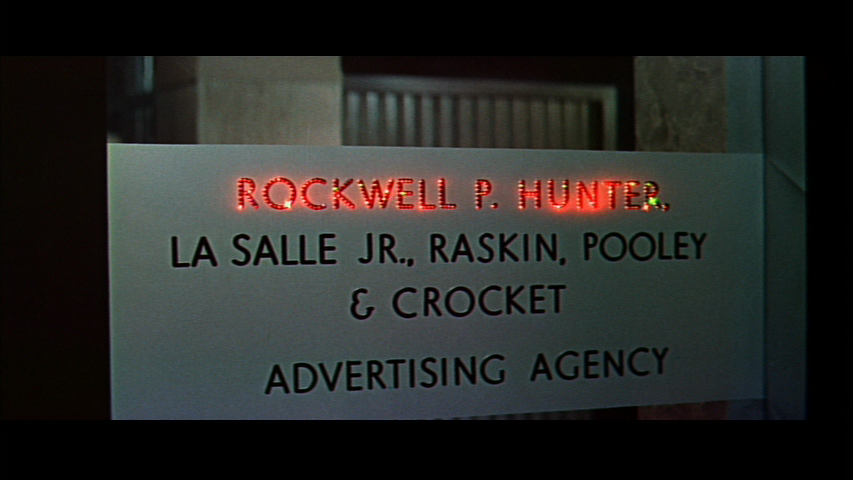

1957 / Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? –– Rock Hunter dances through his empty office at night to an offscreen chorus (“Mr. Successful, You’ve Got it Made”).

U.S. Director: Frank Tashlin. Cast: Tony Randall.

Why It’s Key: In a key satire of the 50s, a Hollywood dream overtly springs to life inside a Hollywood dream.

Madison Avenue adman Rockwell P. Hunter (Tony Randall) signs movie star Rita Marlowe (Jayne Mansfield) to endorse Stay-Put lipstick, thereby making his company a fortune and eventually turning him into first a first a vice president at the ad agency with a key to the executive washroom, then the new president. Before long, even though his alienated fiancée has broken off with him in disgust, he’s clearly “got it made” —- a phrase that he and this movie keep repeating so many times, in so many different ways, like a desperate mantra, that it begins to sound increasingly sinister. Perhaps the most pertinent gloss on this is offered to him by the company’s former president (John Williams), who has meanwhile happily left advertising for horticulture and offers his gloss as a kind of warning: “Success will fit you like a shroud.” Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 5, 2007). — J.R.

A taciturn ex-convict (nonprofessional actor Argentino Vargas) leaves prison after a 20-year sentence and crosses a tropical forest by boat and on foot to find his daughter. This 2004 feature is the second by Lisandro Alonso (La Libertad), a singular and essential figure of the Argentinean new wave; he’s not quite the minimalist some claim, but he can make the simple act of filming feel so monumental that storytelling seems secondary. The hero’s crime, though indicated in the film’s title and opening shot, is acknowledged only fitfully in the spare dialogue, and his killing and gutting of a goat is shown with the same matter-of-factness as his visit to a prostitute. Vargas and the wilderness are such great camera subjects that a sense of quiet revelation is nearly constant. In Spanish with subtitles. 82 min.

Read more

Read more

Writer-director Neil Burger follows his skillful debut feature, the pseudodocumentary thriller Interview With the Assassin (2002), with this spellbinding tale set in Vienna at the turn of the 20th century. Adapted from a Steven Millhauser story, it involves a mysterious magician (Edward Norton) and his amorous attachment to a duchess (Jessica Biel) who’s coveted by the crown prince (Rufus Sewell). This lush piece of romanticism may seem antithetical to Burger’s previous film, but both share a Wellesian integration of the viewer’s imagination and an equally Wellesian preoccupation with power. Paul Giamatti, at his best, plays a police inspector who serves as an audience surrogate; the effective score is by Philip Glass. PG-13, 110 min. Century 12 and CineArts 6, River East 21, Webster Place.

Art accompanying story in printed newspaper (not available in this archive): August 18, 2006. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 4, 2007). — J.R.

I’d like to think Elaine May had it written into her contract that the Farrelly brothers could remake her most brilliant comedy (1972) only if they left her name out of the press materials. She’s lucky to go uncredited (Neil Simon, who wrote the original script, is less fortunate), because you can’t do character-driven comedy without characters, and this one has only grotesques who change traits from moment to moment. Given the joyless vulgarity and absence of laughs, the frenzied changes in locales and character types hardly matter. A guy who sells sporting goods (Ben Stiller) gets married, drives south with his bride (Malin Akerman) on their honeymoon, and promptly falls in love with another woman (Michelle Monaghan) while discovering he hates his wife, but the ethnic humor that gave May’s movie its charge is replaced by crass mean-spiritedness. If I were in movie hell, I’d rather see Good Luck Chuck again than return to this atrocity. R, 115 min. (JR)

Read more

Gabriel Range’s English pseudodocumentary (2006), written with Simon Finch, shows the imagined aftereffects of the assassination of George W. Bush in Chicago in 2007. Some infotainment reports to the contrary, this film in no way celebrates such an event but shows it leading to further legislation curtailing civil liberties in the name of security once Cheney becomes president. And the larger theme, at least by intention, is the consequences of anti-Muslim bias. But the film proceeds more like a mystery thriller than an invitation to reflect, and that theme gets muddled. R, 93 min. (JR) Read more

Juliette Binoche won an Oscar for her role in Anthony Minghella’s adaptation of The English Patient (1996), but in many ways I prefer her soulful performance here: portraying a Bosnian Muslim working as a tailor in London, she’s reason enough to see Minghella’s contrived though absorbing 2006 feature based on his original script. Jude Law (earnest but a bit overtaxed) plays a dissatisfied landscape architect living with a Swedish woman (Robin Wright Penn) and her troubled teenage daughter; his office in the King’s Cross area is twice burglarized by Binoche’s teenage son, and the complicated interactions involving class and culture that ensue between all these characters remain fascinating even when they seem overly schematic. (It’s too bad Minghella’s usual editor, Walter Murch, wasn’t around this time; some of the overly obvious crosscutting suggests the meddling of producer Harvey Weinstein.) R, 120 min. (JR) Read more

From Sight and Sound (January 2007). – J.R.

In order to write briefly about five films that I first saw in 2006 that are especially important to me, I have to violate a taboo against acknowledging works that aren’t (yet) readily available. More specifically, the first two on my list haven’t yet been seen very widely outside of film festivals and/or the countries where they were made, while the last two, even more rarefied, have only been shown under special circumstances, in both cases because their filmmakers are under no commercial pressures to release them and would like to oversee and monitor their exhibition. Although I’m aware that this may irritate some readers, I’d rather address them like adults than succumb to the infantile consumerist model of instant gratification, according to which works should be known about only when they can be immediately accessed. After all, some pleasures are worth waiting for.

Coeurs

Alain Resnais’ dark, exquisite, and highly personal adaptation of Alan Ayckbourn’s Private Fears of Public Places, which I saw at film festivals in Venice and Toronto, is eloquent testimony both to how distilled his art has become at age 84 and how readily Ayckbourn’s examples of English repression can be converted into French equivalents. Read more

Relaxing at a friend’s empty country house, a reclusive New York novelist (David Thewlis) is inspired to write a new story and the next morning wakes up alongside a mysterious and seductive graduate student (Irene Jacob) who quickly becomes his muse and lover. Paul Auster, who made his directing debut with Lulu on the Bridge, provides the voice-over narration for this 2007 second feature, which was drawn and expanded from an interpolated story in his own novel, the engrossing Book of Illusions. The sad irony is that his storytelling gifts, Thewlis’s resourcefulness, and Jacob’s beauty only postpone one’s awareness that the material is too literary to work as cinema. The plot becomes increasingly arch (with the arrival of characters played by Michael Imperioli and by Auster’s teenage daughter, Sophie) and self-consciously metaphysical, and mannerism gradually overtakes visual and narrative invention. 94 min. (JR) Read more