Commissioned by and written for the Italian web site 8 1/2, published in September 2017. — J.R.

When asked what I think about current American cinema, my first response is to ask another question: whose American cinema? Because given the splintering of both the audience and all the possible venues for what we now call American cinema, it’s no longer possible to describe it as a single homogeneous entity.

Perhaps it was always wrong to describe it as such, but when I was growing up in the 1950s, there was still an American cinema that appeared to belong to everyone. Today we have only a series of separate niche markets and venues that seem to exist independently of one another. For the sake of both clarity and candor, I should confess that from 1987 through 2007, I was the principal film critic for the principal alternative newspaper in Chicago, the Chicago Reader, which meant that I was professionally obliged to keep up with what was regarded, rightly or wrongly, as “current American cinema”. Since my voluntary retirement from that post, I’ve been a cinephile with no professional obligations, and my preferences in that capacity have been to systematically avoid films featuring superheroes, most horror films and war films, sports films, blockbusters, and most of the other releases mainly targeted for teenage and preteen boys. Read more

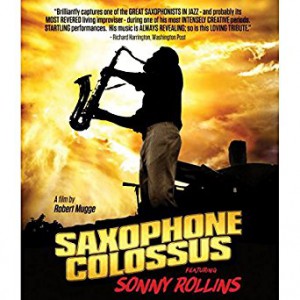

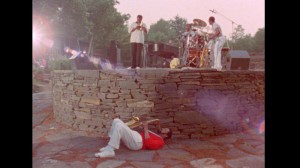

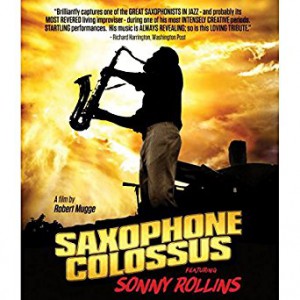

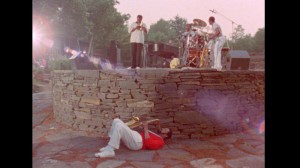

Most of what makes this 1986 Robert Mugge documentary, named after Rollins’ best early album and produced by his late wife Lucille (seen above), so special is Sonny Rollins himself — currently approaching his 87th birthday — as a performer and improviser and his irrepressible stamina and power, combined with his choreographic skill in standing, walking, leaping, and tilting every which way while he plays his tenor sax and pours out his endless inventions. I’ve often thought in the past that jazz vibes players are the most cinematic of performers, because they can only play vibes by dancing, but Rollins has the rare and paradoxical capacity of doing the same thing while looming before us like a veritable mountain. At one point we even see him breaking his heel after leaping from the stage but continuing to play while lying on his back.

The most memorable portions of Saxophone Colossus are two rollicking numbers, “G-Man” and (more abbreviated) “Don’t Stop the Carnival,” performed by Rollins with his quintet at Opus 40, the 6.5-acre environmental sculpture in Saugerties, N.Y. (see above) by the late Harvey Fite (1903-1976), who founded the fine arts program at my alma mater, Bard College. Less memorable to see and hear are portions of a concerto with a symphony orchestra performed at a premiere in Tokyo — not the sort of Third Stream monstrosity one might imagine, but still a composition that unavoidably reins Rollins in, both musically and gymnastically, at the same time that it inflates his cultural profile. Read more

Written for Criterion’s Blu-Ray release of Ozu’s Good Morning and I Was Born, But… in 2017. — J.R.

Structures and Strictures in Suburbia

Jonathan Rosenbaum

From its very opening, Good Morning is deeply and delightfully musical, both in its orchestrations of static visual elements in the first two shots (the juxtaposition of adjacent houses with fences and clotheslines, and all these horizontals with the verticality of electrical towers) and in its varying rhythmic patterns of human movement, which are no less orchestrated, as various figures cross the pathways between houses, between houses and hill, and on top of the hill itself—always, mysteriously, moving from right to left. And what could be more musical than the opening gag, occurring on the same sunny hilltop, of little boys farting for their own amusement, still another form of theme and variations?

All of which prompts me to disagree respectfully with the late Ozu specialist Donald Richie when he maintained, “Good Morning, in some ways Ozu’s most schematic film, certainly one of his least complicated formally, is an example of a film constructed around motifs.” Certainly the motifs are there, and these are vital; the two examined by Richie as sterling examples are the farting and the greeting embodied in the film’s title, and numerous variations are run on both. Read more