Il Cinema Ritrovato DVD Awards 2017

Jurors: Lorenzo Codelli, Alexander Horwath, Lucien Logette, Mark McElhatten, Paolo Mereghetti, and Jonathan Rosenbaum. Chaired by Paolo Mereghetti.

PERSONAL CHOICES

Lorenzo Codelli: Norman Foster’s Woman on the Run (1950, Flicker Alley, Blu-ray). A lost gem rescued by detective Eddie Muller’s indefatigable Film Noir Foundation

Alexander Horwath: Déja s’envolé la fleur maigre (Paul Meyer, 1960, Cinematek/Bruxelles, DVD) and Il Cinema di Pietro Marcello: Memoria dell’immagine (2007-2015, Cinema Libero/Cineteca di Bologna, DVD). Regarding the latter: with this cinematheque-style DVD, subtitled in English and French, one of the greatest contemporary filmmakers, whose work is still under-appreciated outside Italy, receives his rightful chance for global recognition.

Lucien Logette:

Tonka Šibenice (Karel Anton, 1930, Czech Republic, Národní filmový archiv/Filmexport Home Video, DVD)

One of the first Czech sound films. Like many great films of that era, it reflects several influences: expressionism, social realism, Kammerspielfilm, the art of Soviet photography, all used remarkably, without imitation. It contains all the great themes of the end of the silent period: the opposition between the city and the countryside, the misdeeds of modern society, frustrated loves ending in drama, themes served by an astonishing visual beauty.

Mark McElhatten: Kafka Goes to the Cinema (Munich, 4 DVD box set, Edition Filmmuseum). Read more

For Cineaste, Spring 2020. — J.R.

Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes

On Brazil and Global Cinema

Edited by Maite Conde and Stephanie Dennison.

Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2018, 242 pp.,

Hardcover: $199.99, Kindle: $64.60, Paperback (from

University of Chicago Press): $68.00

Brazilian critic, film historian, and teacher Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes (1916-77) is principally known outside of Brazil as P.E. Salles Gomes, the author of the 1957 book Jean Vigo — not only a definitive biography, essential to Vigo’s posthumous rediscovery, first published in France (and translated from French to English in the early 1970s by the author), but also clearly one of the first major critical biographies of any filmmaker in any language. The editors of this volume, however, usually refer to him simply as Paulo Emílio, and picking up on their friendly Brazilian etiquette, I will follow suit.

$68.00 is an outrageous price for a paperback book less than 300 pages long, suggesting a volume intended only for well-funded libraries and professors with institutional perks to spare. But I’m also obliged to report that this first collection by a major and widely neglected figure in film studies redirects my thoughts about cinema like few other recent books. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 27, 2006). — J.R.

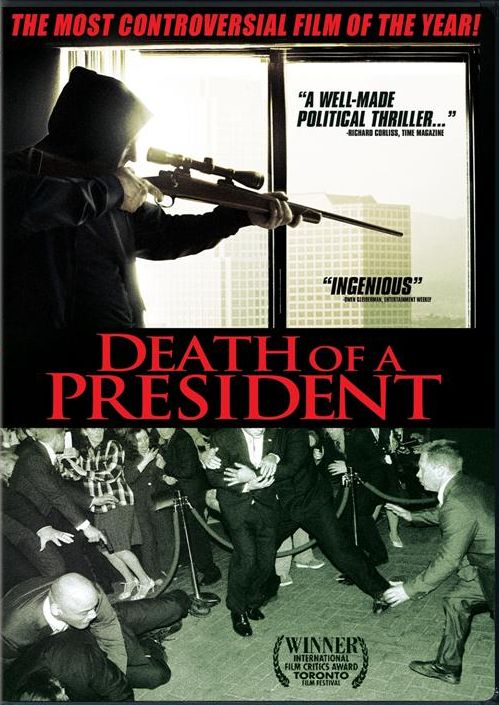

Death of a President **

Directed by Gabriel Range

Written by Simon Finch and Range

With Hend Ayoub, Brian Boland, Patricia Buckley, Jason Abustan, and Chavez Ravine

I dislike few buzzwords more than mockumentary, which even academics now use casually and uncritically. People often assume it’s a neutral descriptive term, but unlike pseudodocumentary — an honest and serviceable label — mockumentary leads many to conclude that the documentary form that’s being imitated is also being made fun of. Most of the works that get labeled mockumentaries are actually honoring the form, by using its techniques to make them seem more real.

According to Wikipedia, the term was first used by Rob Reiner while describing his own This Is Spinal Tap (1984), a popular spoof that led to many successors, including movies directed by Christopher Guest like Best in Show and A Mighty Wind. But these films weren’t so much mocking the documentary form as mocking documentary content. Of course there are films that mock documentary form much more directly, including Peter Watkins’s The Battle of Culloden, Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary, and Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane and F for Fake. Read more

The longest chapter in my book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Arden Press) — which only recently went out of print, though it’s still available from Amazon. I’m sorry that some of the illustrations aren’t of better quality. I’ve done a light edit on the text.

Considering that Benning by now probably has dozens of features to his credit rather than merely four, and that some of these are staggering achievements, I’m not at all sure if my judgments of three decades later would be the same. It’s also worth mentioning that I’ve written about a good many of his subsequent films, including (on this site) Landscape Suicide (1987), Used Innocence (1989), North on Evers (1992), Deseret (1995), Four Corners (1998), Utopia (1998), El Valley Centro (2000), his California Trilogy (2000-2004), Ten Skies (2004), One Way Boogie Woogie/27 Years Later (2005), and RR (2009), often at some length. It’s a pity that most of these films aren’t readily available, but I’m happy to report that the Austrian Film Museum (https://www.edition-filmmuseum.com/) , which published the first substantial book about James Benning in 2007, has launched the long-overdue project of restoring and releasing Benning’s work on DVDs — beginning with American Dreams (lost and found) (1984) and Landscape Suicide, in a two-disc set with a 20-page booklet, for 29,95 Euros, and followed by several more such packages. Read more

My column in Cinema Scope No. 82, Spring 2020. — J.R.

On “A Melody Composed by Chance…” — an excellent new audiovisual analysis of Jacques Demy’s Les demoiselles de Rochefort (1967) on the BFI’s Blu-ray of the film, written and narrated by Geoff Andrew and deftly edited by this disc’s producer Upekha Bandaranayake — I’m grateful to Andrew for correcting the gaffe in my booklet essay claiming that the film’s offscreen ax-murder victim is the Lola (Anouk Aimée) of Demy’s first feature, who subsequently turns up in Model Shop (1969); in fact, it’s the much older Lola-Lola of Josef von Sternberg’s first Marlene Dietrich feature. The other notable extras on this release include “feature-length” audio interviews with Demy (by Don Allen), Michel Legrand (by David Meeker), and Gene Kelly (by John Russell Taylor), Agnès Varda’s essential documentary Les demoiselles ont eu 25 ans (1993), and a fact-filled, critically acute audio commentary by Little White Lies’ David Jenkins — I especially like the way Jenkins cross-references this film with Varda’s underrated Le Bonheur (1965), another film that posits dark ironies behind the Hollywoodish dreams it celebrates.

***

I find it astonishing, really jaw-dropping, that Midge Costin’s mainly enjoyable Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound (2019), available on a UK DVD on the Dogwoof label, can seemingly base much of its film history around a ridiculous falsehood: the notion that stereophonic, multi-track cinema was invented in the 1970s by the Movie Brats — basically Walter Murch, in concert with his chums George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola — finally allowing the film industry to raise itself technically and aesthetically to the level already attained by The Beatles in music recording. Read more

Published by Santa Teresa Press (in Santa Barbara) in 1994 (twenty years later, this book is still available on Amazon) and reprinted in Discovering Orson Welles in 2007, along with the following introductory comments:

Critic Dave Kehr once said to me that encountering The Cradle Will Rock after The Big Brass Ring was a bit like encountering The Magnificent Ambersons after Citizen Kane. I appreciate what he meant — especially when it comes to this script’s nostalgia and its sharp autocritique compared to the more narcissistic and irreverent surface of its predecessor. But I hasten to add that this script, unlike The Big Brass Ring, is more interesting for its autobiographical elements than for its literary qualities. Perhaps for the same reason, writing an afterword about it was more difficult.

On the subject of Tim Robbins’s Cradle Will Rock,I’d like to quote excerpts from an article of mine that appeared in the Chicago Reader on December 24, 1999:

For the past seven months, ever since Robbins’s movie premiered in Cannes, friends and associates who saw it there have been warning me that I, as an Orson Welles specialist, would despise it. Writer-director Robbins does make the character of Welles (Angus MacFadyen) a silly boozer and pretentious loudmouth without a serious bone in his body — something closer to Jack Buchanan’s loose parody of Welles in the 1953 MGM musical The Band Wagon than a historically responsible depiction of Welles in 1937. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 4, 2007). — J.R.

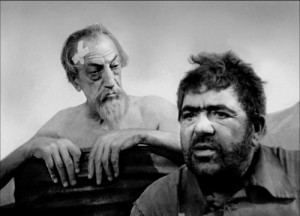

After the more complicated story lines of Satantango and Werckmeister Harmonies, Hungarian master Bela Tarr boils a Georges Simenon novel down to a few primal essentials: a railway worker in a dank and decaying port town witnesses a crime while stationed on a tower and then stumbles into some of the resulting situations. It’s a film about looking and listening, with a suggestive minimalist soundtrack and ravishing black-and-white cinematography by German filmmaker Fred Kelemen. Tarr’s slow-as-molasses camera movements and endlessly protracted takes generate a trancelike sense of wonder, giving us time to think and always implying far more than they show. (As Tarr himself puts it, The camera is inside and outside at the same time.) The fine cast includes Tilda Swinton and Hungarian actress Erika Bok, who played in Satantango when she was 11 and is now in her early 20s. In Hungarian with subtitles. 135 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 7, 2007). — J.R.

One of my all-time favorite films, this beautiful 12-minute short by Charles Burnett (Killer of Sheep, The Glass Shield), made for French TV in 1995, is a jazz parable about locating common roots in contemporary Watts and one of those rare movies in which jazz forms directly influence film narrative. The slender plot involves a Good Samaritan and local griot (Ayuko Babu), who serves as poetic narrator, trying to raise money from his neighbors in the ghetto for a young mother who’s about to be evicted, and each person he goes to see registers like a separate solo in a 12-bar blues. (Eventually a John Handy album recorded in Monterey, a countercultural emblem of the 60s, becomes a crucial barter item.) This gem has been one of the most difficult of Burnett’s films to see. (JR) Read more

I devoted almost an entire page in my first book, a memoir, to this unsung obscurity, a low-budget comedy western that I saw in Florence, Alabama with my brother Alvin on November 14 or 15, 1951, when I was eight and he was six, on a double bill with Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Man from Planet X. I can very nearly classify this viewing as my first cinematic encounter with the avant-garde, by which I mean something akin to what J. Hoberman calls Vulgar Modernism — eight months after what might have been my first non-cinematic encounter with the avant-garde when I attended a Spike Jones concert one Sunday afternoon at the Sheffield Community Center. Bear in mind that I saw Skipalong Rosenbloom a full year before the first issue of Mad (the comic book) appeared and almost two years before I bought my first issue (no. 6, August-September 1953); this was also a full year before I saw Frank Tashlin’s Son of Paleface. It’s quite possible, of course, that I’d already seen one of Tex Avery’s cartoons by then, but if I had, this fact couldn’t be traced by the same methods of research that I employed in my memoir, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, which mainly involved combing back issues of the local Florence newspaper on microfilm for movie ads. Read more

Written at the request of Jae-cheol Lim, the editor of this Korean edition of Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (second edition, 2008), which was translated by Ahn Kearn Hyung and was published in late February 2016. Now that three copies of this hefty volume have just arrived in the mail (637 pages long, which is considerably more than the 449 pages of the original, apparently due in part to a different font size), this seems like a good time to repost the new Afterword. 2018 Postscript: I now regret including No Home Movie on my list, the only new selection I’ve changed my mind about. — J.R.

Afterword to the Korean Edition of ESSENTIAL CINEMA (January 2016):

The closer one comes to the present, the harder and more hazardous it becomes to compile a list of the best films. As I’ve recently pointed out elsewhere, one should consider the lengths of time between Jean Vigo’s death and the first appearances of Zéro de conduite and L’Atalante in the U.S. (thirteen years), or between the first screening of Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 and its recent appearances on Blu-Ray (forty-five years), and it becomes obvious that the popular custom of listing the best films of any given year is unavoidably a mythological undertaking derived more from faith than from any secure knowledge. Read more

Filmmaker Azazel Jacobs calls this a story about stolen love and stolen identities shot on stolen film. He’s the son of Ken Jacobs (Star Spangled to Death), with some of his pa’s anarchic spirit, and because he apparently stole good 35-millimeter stock, he doesn’t have to worry that much about the story anyway. The slender premise — two guys are named Rodolfo, one of whom gets renamed Depresso by the girlfriend of the other — seems mainly an excuse to hang out with these people, and it’s a tribute to Jacobs’s skill that this is enough. He knows how to put air around his characters, pace their movements, and chart their interactions in various locations, and when the heroine starts dancing at one point, she’s so good that I wanted to cheer. 77 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

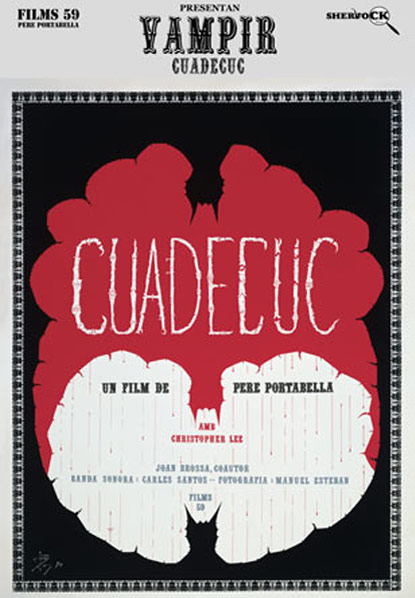

The following essay was commissioned by Pere Portabella himself in 2009 when he was planning to include some written materials with a DVD box set of his complete works — a box set that he eventually decided to release four years later without any written material. This essay has subsequently appeared in my 2010 collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia and, in Spanish translation, in El mundo in March 2013. — J.R.

Filmmakers who reinvent the cinema for their own purposes generally operate under certain distinct handicaps. In a few privileged cases (Griffith, Feuillade, Chaplin, Hitchcock) it’s the cinema itself, as art form and global institution, that winds up readjusting to the reinvention. But what happens more often is either a prolonged banishment of the filmmaker’s work from public awareness or a protracted series of misunderstandings until (or unless) the new rules are recognized, understood, and assimilated.

In the case of Pere Portabella, where some of the principles of production, distribution, and exhibition have been reinvented along with some concepts of reception, the frequent time lags between completed projects have only exacerbated some of the difficulties posed to uninitiated viewers. Interestingly, these difficulties have relatively little to do with an audience’s receptivity to the films themselves and a great deal to do with an audience discovering the very fact of their existence. Read more

From Kevin Lee’s web site, posted circa 2004. — J.R.

The following questions for Jonathan Rosenbaum were compiled by myself and esteemed colleagues at the IMDb Classic Film Board. They were e-mailed to Rosenbaum on the occasion of the release of his book ESSENTIAL CINEMA. His responses appear after each question.

Q- I was actually quite surprised when I saw that your book argued for the necessity of canons, given your previous criticism of the AFI’s top 100 lists and how it institutionalizes popular taste in much the same way as any canon does. Also, you testify to the profound affect that the Sight and Sound top 10 list had on you during your college years (as was the case for me) — but couldn’t one say that this, or any list, may be as limiting in its own way (in the perspective it espouses) as the AFI list? If the goal is to encourage people to see as many things as possible, I wonder if any canon or list alone is up to that task. Would you agree to that the problem is not in these canons or lists but in our attitudes towards them (for example, I don’t think it was the virtue of the Sight and Sound list in itself, but your attitude towards it, that made it worthwhile)? Read more

Written for Criterion’s DVD release of F for Fake in 2005. — J.R.

There were plenty of advantages to living in Paris in the early 1970s, especially if one was a movie buff with time on one’s hands. The Parisian film world is relatively small, and simply being on the fringes of it afforded some exciting opportunities, even for a writer like myself who’d barely published. Leaving the Cinémathèque at the Palais de Chaillot one night, I was invited to be an extra in a Robert Bresson film that was being shot a few blocks away. And in early July 1972, while writing for Film Comment about Orson Welles’s first Hollywood project, Heart of Darkness, I learned Welles was in town and sent a letter to him at Antégor, the editing studio where he was working, asking a few simple questions—only to find myself getting a call from one of his assistants two days later: “Mr. Welles was wondering if you could have lunch with him today.”

I met him at La Méditerranée — the same seafood restaurant that would figure prominently in the film he was editing — and when I began by expressing my amazement that he’d invited me, he cordially explained that this was because he didn’t have time to answer my letter. Read more

Written originally for Trafic no. 12 (Fall 1994), where it appeared in French translation, translated by Bernard Eisenschitz; all three letters first appeared in English in Persistence of Vision No,. 11, 1995. — J.R.

June 13, 1994

Dear Bill,

It’s good to have all your multifaceted thoughts about It’s All True, which makes your letter worth the long wait. I especially value what you have to say regarding the political implications of the film in the 1940s as well as the 1990s, because it seems that those implications have mainly eluded critics in both decades. As you well know, it wasn’t until Robert Stam published “Orson Welles, Brazil, and the Power of Blackness” in the seventh issue of Persistence of Vision (1989), with corroborating essays by both Catherine and Susan Ryan, that it finally became clear, forty-odd years after the event, that part of what was rattling so many studio executives and Brazilian government officials alike about Welles’s behavior in Rio was his particular interest in blacks. Maybe you’re right that he wasn’t a radical, but if It’s All True had been completed and released in the early 1940s, it still might have offered a radical precedent: three Latin American stories focusing on non-white heroes. Read more