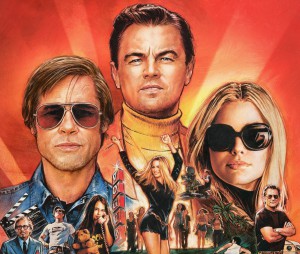

The Spanish monthly film magazine that I write for, Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, invited me in the summer of 2019 to expand on my latest column for them as well as a few Facebook posts about Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Here is the result. — J.R.

Has 9/11 or the war on terror had any impact on you personally or creatively?

9/11 didn’t affect me, because there’s, like, a Hong Kong movie that came out called Purple Storm and it’s fantastic, a great action movie. And they work in a whole big thing in the plot that they blow up a giant skyscraper. It was done before 9/11, but the shot almost is a semi-duplicate shot of 9/11. I actually enjoyed inviting people over to watch the movie and not telling them about it. I shocked the shit out of them. But, again, I was almost thrilled by that naughty aspect of it. It made it all the more exciting.

But on some level you must have been caught up in the reality of 9/11.

I was scared, like everybody else. “OK, what is this new world we’re going to be living in? Is it going to be fucking Belfast here?” And I didn’t want to fucking fly nowhere. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1976. — J.R.

Prividenie, Kotoroe ne Vozvrashchaetsya

(The Ghost that Never Returns)

U.S.S.R., 1929

Director: Abram Room

In an unidentified South American country, José Real is serving a life sentence for having led an oilfield workers’ strike ten years earlier. After another prisoner breaks away from guards to tell him that the prison governor has a letter from his wife, and then leaps to his death, Real leads a revolt among the prisoners. The governor orders that they be sprayed with hoses; the revolt subsides, and Real is locked into a narrow cupboard. Conferring with the chief of the secret service, the governor recalls the regulation whereby a prisoner who has served ten years is entitled to one day’s liberty and decides to grant this to Real, with the understanding that he will be killed at the day’s end for trying to ‘escape’. After being shown his wife’s letter and hearing from a newly arrived prisoner that a new strike is planned at Hillside Well, Real agrees to go. Five days later – after news of his imminent arrival has reached his family, their neighbors and the oilfield workers — he sets out, warned that no one who has taken this leave has ever made it back alive. Read more

My Winter 2019 column for Cinema Scope. — J.R.

Some of Roman Polanski’s early features — Repulsion (1965), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Tess (1979) — are centred on vulnerable women, but as Bitter Moon (1992) makes abundantly clear, these are all films predicated on the male gaze, as are the more recent and more impersonal films of his that come closest to qualifying as Oscar bait (The Pianist [2002], arguably The Ghost Writer [2010], and, I would presume, An Officer and a Spy). Bitter Moon even problematizes this fact by assigning that gaze to two mainly unsympathetic males (Peter Coyote and Hugh Grant), and defining it mostly as poisonous, and Venus in Fur (2013) carries this tendency further by explicitly labelling it sexist, meanwhile making the male figure (Mathieu Almaric) almost a dead ringer for Polanski as a young man. Based on a True Story (2017), by focusing almost exclusively on two women (Emmanuelle Seigner and Eva Green), seeks to minimize the male gaze even more, not so much by problematizing it as by making it closer to irrelevant. Polanski himself comments on this fact in the interview included on the Spanish DVD of this film (apparently the only way it can be seen with English subtitles translating its French dialogue, which is how I finally managed to catch up with it). Read more

From the Summer 2019 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

Readers of Movie Mutations, the 2003 collection I co-edited with Adrian Martin, will know that the Jungian notion of global synchronicity has long been a preoccupation of mine. One striking recent manifestation of this phenomenon came to light when I read, around the same time, Mark Peranson’s editor’s note about Documentary Now! in the last issue of this magazine, and a ramble from David Thomson about binge-watching TV in the April Sight & Sound, both of which compelled me to finally take out a trial subscription to Netflix and spend the better part of a weekend binge-watching Series One and Two of Babylon Berlin (12 hours) and the even more absorbing Russian Doll(four hours) via streaming — just before receiving a four-disc PAL DVD box set of the former from Acorn Media International on Monday. All of which suggests that Mark, D.T., Acorn, and I have mysteriously been on roughly the same market wavelengths regardless of our illusions of free choice.

There’s a real danger that streaming may eventually make the name of this column anachronistic, so for the time being please allow me to include that viewing option, as I’ve already done with Blu-rays. Read more

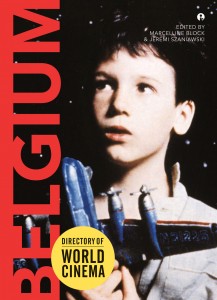

In today’s mail: Directory of World Cinema: Belgium, edited by Marcelline Block and Jeremi Szaniawski. Bristol, UK/Chicago, USA: Intellect Books, 332 pp., $31.95 from Amazon.

Discovered today on the Internet (at YouTube): 17 films by James Benning: five shorts (Two Cabins, Short Story, Two Faces, Postscript, Youtube) and a dozen features (Twenty Cigarettes, Ten Skies, One Way Boogie Woogie, Easy Rider, The War, Faces, After Warhol, Small Roads, Nightfall [see above photo], BNSF, casting a glance, Stemple Pass).

In both cases, untold riches. Just for starters, the book offers countless reviews and essays by 38 contributors exploring multiple facets of a neglected subject, the first detailed account I know in English of all the features of André Delvaux, fascinating interviews with Chantal Akerman and Boris Lehman (including the former’s description of The Misfits as “a documentary about Marilyn Monroe undergoing a depression” and the “extremely accurate, just relationship” between people and space in John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath), reflections on Jean-Claude Van Damme and “Belgium as Cinematic ‘Non-space’”. The Benning bounty includes five film that I’ve already seen and a dozen more that I haven’t . Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 24, 1993). — J.R.

LAST ACTION HERO

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John McTiernan

Written by Shane Black, David Arnott, Zak Penn, and Adam Leff

With Arnold Schwarzenegger, Austin O’Brien, Charles Dance, Anthony Quinn, Tom Noonan, Mercedes Ruehl, F. Murray Abraham, and Robert Prosky.

The word is out: Last Action Hero is an unmitigated disaster. The sound of studio panic was plainly audible in a report in the June 17 New York Times that Columbia Pictures threatened to sever all communications with the Los Angeles Times if it didn’t guarantee it would “never again run a story written or reported by Jeff Wells about (or even mentioning) this studio, its executives, or its movies.” Wells’s crime was a June 6 article in the Los Angeles Times reporting that a test-marketing preview of Last Action Hero held in Pasadena about two weeks earlier had been disappointing. The article contained “categorical denials” from several studio executives that such a screening had ever taken place, but clearly this wasn’t enough for the industry people. As Wells told the New York Times, “You’re talking about a studio in a major meltdown mode. These guys are blitzing out here.”

I read this story only hours before seeing another “disappointing” preview of Last Action Hero in Chicago, after several weeks of hearing rumors that the picture was a “mess” and in deep, deep trouble. Read more

This is my Introduction to The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S., a catalogue/ collection put together to accompany a film series at the Austrian Filmmuseum and the Viennale in Autumn 2009. — J.R.

I cannot tell a lie: the initial concept and impulse behind this retrospective weren’t my own. More precisely, they grew out of a series of email exchanges between myself and Hans Hurch and/or Alexander Horwath last April. Everything started when Hans proposed that I select a program devoted to American film comedy, “not as a history or anthology of the genre but in a more open and at the same time more concrete way…not [to] just dedicate it to comedy as such but to various aspects, different forms, ideas, and functions of the comic – from the earliest works of American cinema to recent films.”

Over three months later, I think it’s safe to say that I’ve fulfilled this proposal, at least if one can accept a fairly loose definition of “earliest” (i.e., 1919 –- which is already a good quarter of a century into what might be described as the history of American film, describing my own limitations better than the limits of my subject.) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 19, 1996). — J.R.

Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie 0 (no stars)

Directed by Jim Mallon

Written by Michael J. Nelson, Trace Beaulieu, Mallon, Kevin Murphy, Mary Jo Pehl, Paul Chaplin, and Bridget Jones

With Beaulieu, Nelson, Jeff Morrow, Rex Reason, Faith Domergue, and the voices of Mallon and Murphy.

The premise of the recently discontinued cable-TV series on which this film is based is more or less as follows: a blustering mad scientist named Dr. Clayton Forrester (Trace Beaulieu) plots to take over the world. His plan? According to the Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie press book: “Find the worst movies ever made, show them to the entire population and bring the planet to its knees.” He kidnaps Mike Nelson (Michael J. Nelson) to serve as a guinea pig, takes him to the Satellite of Love, and makes him and his three robot pals — Tom Servo, Gypsy, and Crow — watch the Worst Movies Ever Made. But Mike and his friends confound the experiment by talking back to the screen and making wisecracks. We watch the movies too — or parts of them, since the lower portion of the screen is partially blocked by the silhouettes of Mike and two of the robots. Read more

Posted on the web site Wellesnet. I’ve added a few illustrations of my own to the original, conducted by Lawrence French.

Having worked as a consultant on the completion of The Other Side of the Wind, I’m no longer sure that all my comments about the film found below would still hold. — J.R.

Jonathan Rosenbaum has long been an astute critic on the cinema of Orson Welles, frequently writing about Welles’ films. He served as the consultant for the re-edited version of TOUCH OF EVIL, and edited THIS IS ORSON WELLES, the seminal book of Welles interviews, conducted by Peter Bogdanovich.

The following interview has been combined from two separate conversations. The first took place in the fall of 1998, after the release of the re-edited version of TOUCH OF EVIL, and focused on the problems inherent in changing TOUCH OF EVIL to what Welles requested in a memo written 41 years earlier. The second interview occurred in January, 2003, and covers Welles’ two

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Does the film museum in Munich now have most of the unfinished Welles films? Read more

From Cineaste, Vol. XXXIII, No. 4, 2008. -– J.R.

1) Has Internet criticism made a significant contribution to film culture? Does it tend to supplement print criticism or can it actually carve out critical terrain that is distinctive from traditional print criticism? Which Internet critics and bloggers do you read on a regular basis?

1) a. Significant and profound. Because the changes it has wrought are ongoing and unfolding, it’s still hard to have a comprehensive fix on them.

1) b. It can and does do both. By broadening the playing field in terms of players, methodologies, audiences, social formations, and outlets, it certainly expands the options. The interactivity of almost immediate feedback, the strengths and limitations of being able to post almost as quickly as one can think (or type), the relative ease of making screen grabs — these and many other aspects of Internet discourse are bringing about changes in content as well as in style and form, shape and size.

1) c. Here’s just a sample: To varying degrees (some much more regularly than others), I like to read Acquarello, David Bordwell, Zach Campbell, Fred Camper, Roger Ebert, Flavia de la Fuente, Filipe Furtado, Michael E. Read more

My 30th “En Movimiento” column for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, formerly known as the Spanish Cahiers du Cinema, written in late January, 2013. — J.R.

The debates about Kathryn Bigelow and Mark Boal’s Zero Dark Thirty in the United States have been substantial. Critical positions have ranged from Ignatiy Vishnevetsky’s measured defense at mubi.com/notebook/posts to Steve Coll’s attack in The New York Review of Books (to cite two of the less hysterical and more intelligent responses), and have only been exacerbated by the five Academy Award nominations the film has received. When I finally saw the film myself, it was apparent that part of the controversy derived from a certain ambiguity in the film’s depiction of torture, made all the more ambiguous by the filmmakers’ misleading and mainly unconvincing claims of political neutrality — a battle still being waged in the February issue of Sight and Sound, where Nick James, the editor of that English monthly, begs to differ with the negative judgments of two of his writers towards the film, even though he concedes that Bigelow’s naïve contention that “The film doesn’t have an agenda, and it doesn’t judge” has only helped to confuse matters.I agree with James that the climactic killing of Osama bin Laden registers largely as a hollow and morally dubious victory, but I also believe that the film’s commercially motivated attempt to be circumspect about its overall critical position makes it easy to misinterpret. Read more

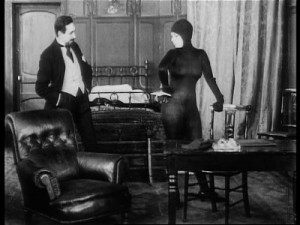

From the October 9, 1987 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Louis Feuillade’s extraordinary ten-part silent serial of 1916, running just under eight hours, is one of the supreme delights of film–an account of the exploits of an all-powerful group of criminals called the Vampire Gang, headed by the infamous Irma Vep (Musidora), whose name is incidentally an anagram for “vampire.” Filmed mainly in Paris locations, Feuillade’s masterpiece combines documentary with fantasy to create a dense world of multiple disguises, secret passageways, poison rings, and evil master plots that assumes an awesome cumulative power: the everyday world of the French bourgeoisie, personified by the hapless sleuth hero, during the height of World War I is imbued with an unseen terror that no amount of virtuous detection can ever efface entirely. (Significantly, as in many of Feuillade’s other serials, the villains are a good deal more fascinating than the relatively square hero, although a comic undertaker and the leader of a rival gang are periodically on hand to help him out.) Because none of Feuillade’s complete serials is available in the U.S., this special screening helps to fill an enormous gap in our sense of film history. One of the most prolific directors who ever lived, Feuillade is today arguably a good deal more entertaining than Griffith, and unquestionably much more modern: his mastery of deep-focus mise en scene is astonishing, and its influence on Fritz Lang as well as Luis Bunuel and other Surrealists remains one of his major legacies. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October, 1990). — J.R.

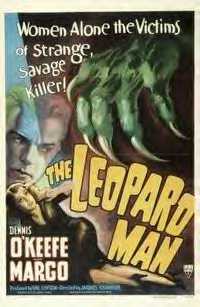

This economically constructed and haunting chiller (1943, 66 min.) from the inspired team of producer Val Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur doesn’t have the reputation of the two other films they worked on together in the early 40s, Cat People and I Walked With a Zombie. In part that’s because its ending is a bit abrupt and unsatisfactory — but it’s still one of the most remarkable B films ever to have come out of Hollywood. Adapted from Cornell Woolrich’s novel Black Alibi by Ardel Wray and Edward Dein, the film employs an audacious narrative of shifting centers, thematically related by a string of grisly murders in a small town in New Mexico. Depending for much of its effect on a subtle and poetic nudging of the spectator’s imagination, the film has a couple of sequences that are truly terrifying. With Dennis O’Keefe, Margo, and Jean Brooks. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From Cinemad No. 3 (2000). Much of this piece makes me blush, and other parts are clearly out of date, but I’m posting this basically “for the record”. -– J.R.

A conversation with film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum by Paolo Ziemba

This being the first article that I’ve written for Cinemad I thought it was more than appropriate to delve into a time where films changed my way of thinking of the world. Rosenbaum was key in this new beginning. Cinemad continues this process. While reading Rosenbaum’s books for research I experienced a sort of nostalgia for the days back when I was broadening my knowledge of cinema. Rosenbaum had opened many doors to a world of cinema that I had never experienced before. With this in mind I would like this article, at the least, to stir the readers to explore what Rosenbaum, and the world of cinema, is more than willing to offer.

Imagine a film critic who travels the world and experiences all cinema. Imagine a critic who is not only moved by cinema because of its beauty, but also because of its importance in the world. Imagine a critic who takes all of this in and then serves it to anyone willing to read. Read more

From Film Comment (July-August 1977). After I returned to the U.S. early that year after seven and a half years of living in Europe (Paris and London), my “Paris Journal” and “London Journal” column in Film Comment became “Moving,” a preoccupation that eventually yielded the title of my first book, Moving Places.

Note: the 35 mm screening of JEANNE DIELMAN alluded to here was set up by Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson on the University of California, San Diego campus while they were working on the last of their essays. -– J.R.

How to keep moving in the same way that this column must travel — from La Jolla, to Richard Corliss in Cannes, to Film Comment in New York, to wherever you happen to be reading it? Now that TV Guide generally has to take the place of Pariscope, [London’s] Time Out, the New York newspapers, shall I write about the breathneck beginning of Sirk’s SLEEP, MY LOVE, the parallels with Preminger’s WHIRLPOOL,a wonderful exchange between Don Ameche and Hazel Brooks (”Doesn’t sound like my girl…” “You have a lot of girls. This is one of them”), or scenes that unexpectedly and mysteriously take place in the rain? Read more