The following was commissioned in 1999 by Written By, the magazine of the Writers Guild, which decided not to run it because Brooks’s agent refused to let me see The Muse in advance for this article unless a “cover story” was promised. Written By, to its credit, refuses to make deals of this kind. So the magazine paid me for the article and didn’t run it, which I hope made Brooks’s agent properly proud of his efforts. — J.R.

You may recall him as the wealthy convict in Out of Sight, or, prior to that, as Cybill Shepherd’s wisecracking cohort at the campaign headquarters in Taxi Driver, as Holly Hunter’s best friend in Broadcast News, or as the neurotic Hollywood producer in I’ll Do Anything. Maybe, if you’re luckier, you’ve seen his five underrated and highly durable comedies — Real Life (1979), Modern Romance (1981), Lost in America (1985), Defending Your Life (1991), and Mother (1996) — which will be succeeded later this year by The Muse.

Albert Brooks has so far taken solo writing credit only on Defending Your Life — sharing script credit with TV comedy writer Monica Johnson on the other four (as well as on The Scout, a disappointing 1994 baseball movie he didn’t direct), and also with Harry Shearer on Real Life, the first and probably the funniest of the lot. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 30, 2004). — J.R.

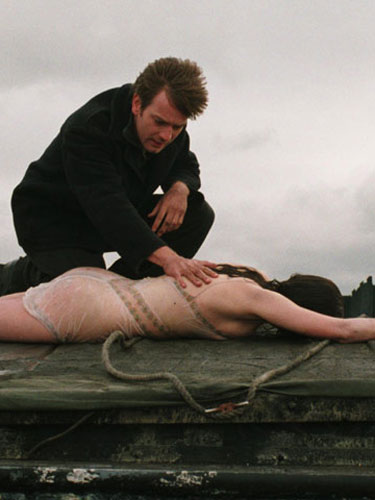

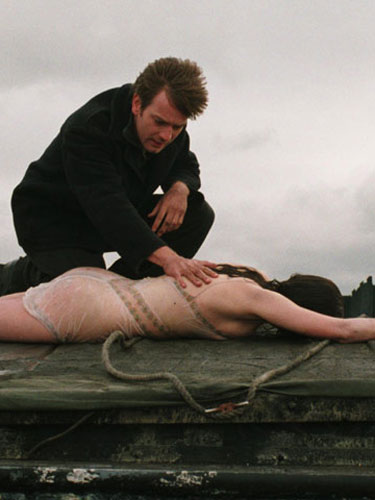

David Mackenzie’s compelling and authoritative adaptation of Alexander Trocchi’s 1953 novel revolves around a nihilistic bargeman (perfectly embodied by Ewan McGregor) who works the canals between Edinburgh and Glasgow and spends all his free time reading and screwing (often adulterously). This emotional detachment is often treated as an existential position, so the story occasionally suggests a beat version of Camus’ The Stranger, with the images’ sensual and erotic power often superseding any literal meaning. Despite the flashback structure, this is a film in which mood matters more than plot, while the hero’s heroic stature steadily shrinks. All in all, a very impressive second feature. With Tilda Swinton (The Deep End), Peter Mullan (My Name Is Joe), and Emily Mortimer. NC-17, 93 min. Century 12 and CineArts 6, Pipers Alley.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 7, 2005). — J.R.

Ten film critics’ polls in Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, Toronto, and Washington, D.C., have named Sideways the best movie of the year. I don’t know whether to laugh or cry.

It’s not that I have anything against comedies; last year Down With Love was second on my ten-best list. Besides, Sideways has a dark side — its infantile hero (Paul Giamatti) steals from his mother, and his infantile sidekick (Thomas Haden Church), who’s about to be married, compulsively cheats on his fiancee. They behave as if the world beyond southern California doesn’t exist, but the movie doesn’t seem to realize it. And like most American mainstream movies, it dances around class issues without ever facing them.

If my colleagues who love this movie, many of whom I admire, are implying that it contains valuable life lessons, I wish they’d tell me what they are. Giamatti is an acerbic loser hero who’s eventually given a ray of hope, like the Woody Allen hero of 20 or 30 years ago but without the wisecracks. So is regressing to that moviemaking model the proudest achievement of world cinema in 2004? Did the critics find something comforting, even affirmative, about its provincialism? Read more