The following was written to accompany a film series put together by Ehsan Khoshbakht, Imogen Sara Smith, and myself for a tour in Turkey in late 2018 sponsored by the American Embassy. I don’t know if it was used in this form. — J.R.

“Fake news”, the term paradoxically used by Donald Trump for journalism that exposes his own lies and corruption, evokes what George Orwell called New-speak in 1984, whose slogans included “war is peace” and “ignorance is strength”. Trump’s cleverness as a media manipulator consists of appropriating the very term that describes his own practice while reversing its meaning so that his opponents — including the people who put together this film program about “fake news,” my colleagues and myself — can no longer use it without speaking on Trump’s behalf. This is surely manipulation with a vengeance, where control over both language and presence becomes another form of class inequality. So when TV executives remark that Trump is bad for America but good for television, they’re only suggesting that these two latter entities have separate agendas and even separate owners, neither of which happens to be the American public.

Feeding public fears with worst-case scenarios is the principal form of press manipulation found in Try and Get Me! Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 2002). — J.R.

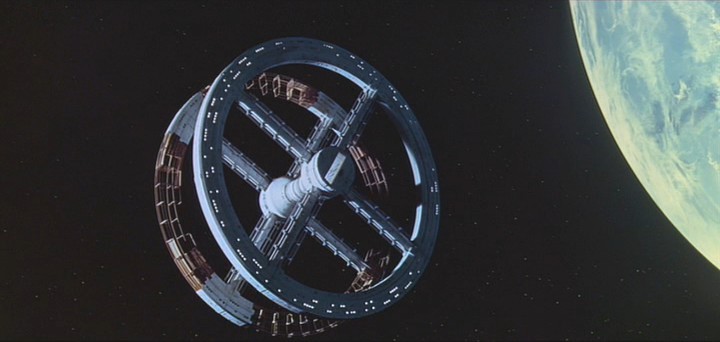

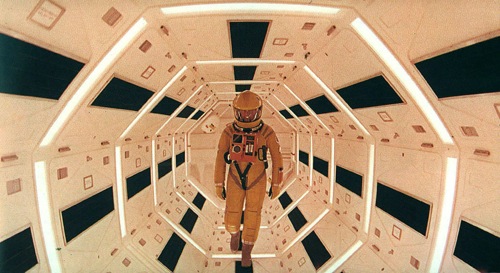

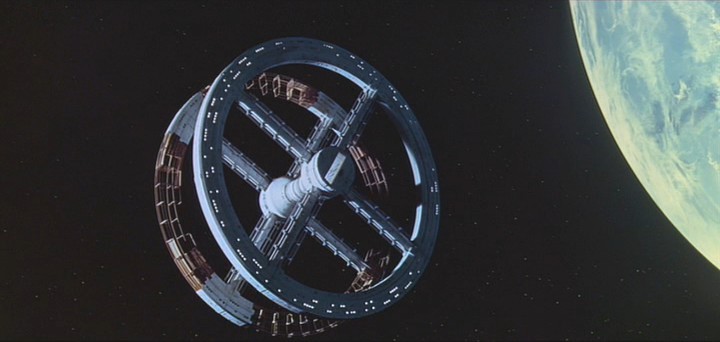

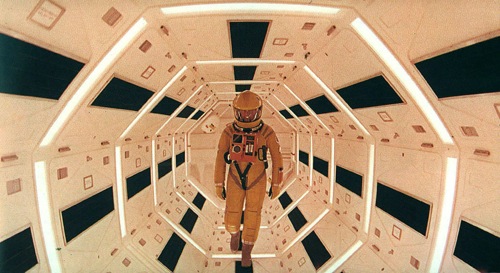

Seeing this 1968 masterpiece in 70-millimeter, digitally restored and with remastered sound, provides an ideal opportunity to rediscover this mind-blowing myth of origin as it was meant to be seen and heard, an experience no video setup, no matter how elaborate, could ever begin to approach. The film remains threatening to contemporary studiothink in many important ways: Its special effects are used so seamlessly as part of an overall artistic strategy that, as critic Annette Michelson has pointed out, they don’t even register as such. Dialogue plays a minimal role, yet the plot encompasses the history of mankind (a province of SF visionary Olaf Stapledon, who inspired Kubrick’s cowriter, Arthur C. Clarke). And, like its flagrantly underrated companion piece, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, it meditates at length on the complex relationship between humanity and technology — not only the human qualities that we ascribe to machines but also the programming we knowingly or unknowingly submit to. The film’s projections of the cold war and antiquated product placements may look quaint now, but the poetry is as hard-edged and full of wonder as ever. 139 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1994). — J.R.

Roman Polanski’s second British film (Repulsion was the first) is a mean little absurdist comedy (1966) set on a remote Northumberland island; it’s also one of the best and purest of all his works. An odd couple (Donald Pleasence and Françoise Dorleac) living in an isolated castle find their world invaded by two doomed gangsters on the run (Lionel Stander and Jack MacGowran), and the ensuing standoffs are funny, cruel, disquieting, and unpredictable, especially after various other unwelcome guests turn up. Stander is especially good — this may be the definitive performance of the blacklisted gravel-voiced character actor, best known for his 30s and 40s work. With Robert Dorning and Iain Quarrier; watch for Jacqueline Bisset as one of the guests. 111 min. (JR)

Read more