From the Chicago Reader (June 28, 2002). — J.R.

Minority Report *** (A must-see)

Directed by Steven Spielberg

Written by Scott Frank and Jon Cohen

With Tom Cruise, Colin Farrell, Samantha Morton, Max von Sydow, Lois Smith, Peter Stormare, Tim Blake Nelson, Steve Harris, and Kathryn Morris.

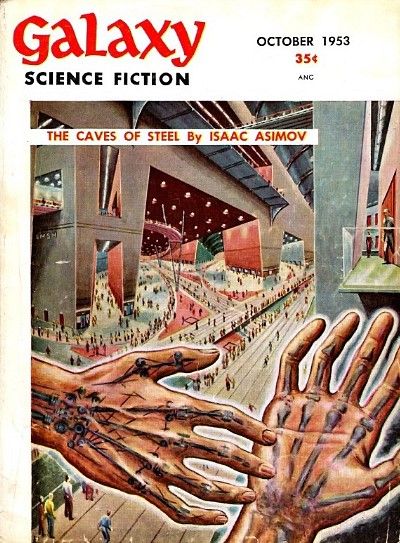

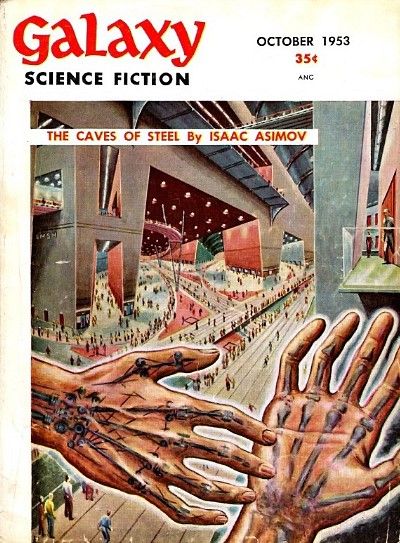

Since my early teens I’ve been stubbornly clinging to a copy of the October 1953 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction magazine, featuring the first installment of Isaac Asimov’s The Caves of Steel, a mystery story set in a vast city of the future. I prize this particular issue not for anything inside but for the cover illustration by “Emsh,” the name future filmmaker Ed Emshwiller used to sign his artwork. In the foreground two transparent hands — one revealing human bones, the other metal ones — are shown in front of the vast reaches of an enclosed cityscape with pedestrians. This encouraged me to consider not only a future city but also how it might look to both a human and a robot detective.

No story, by Asimov or anyone else, could do as much for my imagination as that Emsh cover. The only thing that came close was a single sentence by Damon Knight in his review of Asimov’s novel, which may have been what led me to the novel and that issue of Galaxy in the first place: “Asimov has turned a clear, ironic, and compassionate eye on every cranny of the City: the games children play on the moving streets; the legends that have grown up about deserted corridors; the customs and taboos in Section kitchens and men’s rooms; the very feel, smell, and texture of those steel caves in which men live and die.” Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 503). I think I must have permanently jinxed the possibility of ever becoming a friend of Pauline Kael’s by introducing myself to her after the New York Film Festival’s press screening of Get Out Your Handkerchiefs in 1978. Clearly enraptured, she promptly asked me what I thought of the film, and I replied, “Well, at least it’s better than Les valseuses,” which she deeply revered as well. — J.R.

France, 1974

Director: Bertrand Blier

After harassing a woman in the street and stealing her purse, Jean-Claude and Pierrot steal a Citroen for the afternoon; when they return it, the hairdresser owner holds them at gunpoint until they manage to escape during a scuffle, taking the hairdresser’s girlfriend Marie-Ange with them. Pierrot, however, is shot in the groin; the two force a surgeon to treat the wound and then take his money. When they abandon another stolen car to hop a train, Jean-Claude pays a young mother to suckle Pierrot before she gets off to meet her soldier husband. They take another train to the town of Briddle, where they break into a house whose owners are away but where they excitedly discover the underwear of teenager Jacqueline. Pierrot continues to fret about being impotent, and is annoyed when Jean-Claude forcibly sodomises him; they visit Marie-Ange and take turns having sex with her, although she remains frigid. Read more

Written for the February 2013 issue of Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, as one of my bimonthly columns for that magazine (“En movimiento”). It continues to amaze me how American movies who preach the inescapable inevitability of corruption in American life — Citizen Kane, the Godfather films, and now Lincoln and Zero Dark Thirty — are invariably regarded as more profound and much likelier to wind up as Oscar fodder than those that are less resigned to accepting corruption. — J.R.

Two inordinately praised big-studio releases of the holiday season, Lincoln and Argo, seem to depend in part on the innocence of the American audience in order to score their ideological successes. The first of these, a high-minded art movie, starts with a familiar subject, while the second –- which, I must confess, I’ve only sampled — incorporates the relative unfamiliarity of Iranian culture as part of its action-thriller mechanics. That both films have been overpraised seems hard to dispute; “Long after its commercial run, Lincoln will remain an invaluable teaching tool,” Joe Morgenstern declared characteristically in the Wall Street Journal, while Rex Reed, no less typically in the New York Observer, called Argo, “A movie that defines perfection. Read more