From the Chicago Reader (January 12, 1998). — J.R.

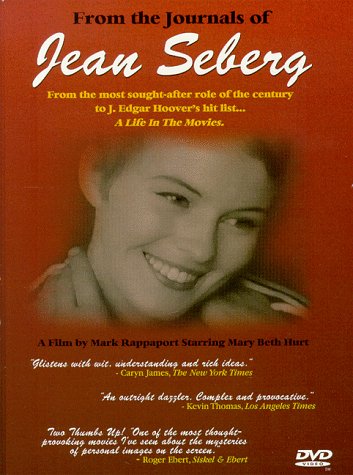

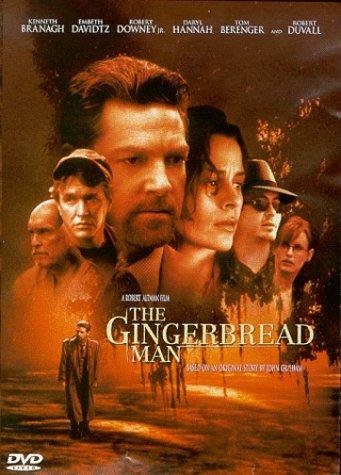

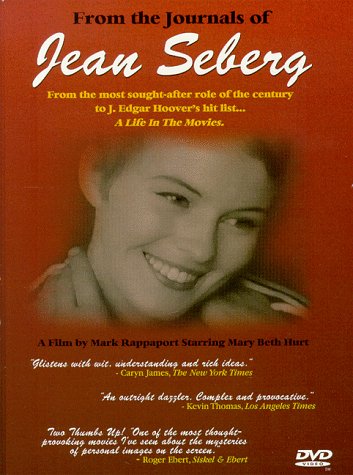

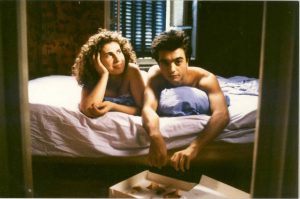

From the Journals of Jean Seberg

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Mark Rappaport

With Jean Seberg and Mary Beth Hurt.

For most of the remainder of this month the Film Center is presenting the U.S. theatrical premiere of Mark Rappaport’s From the Journals of Jean Seberg, and using this occasion to show some other important programs as well. We had revivals of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, featuring one of Seberg’s key early performances, and Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), both important touchstones in Rappaport’s film — the second as a cross-reference to Seberg’s first film, Saint Joan. This week, in addition to seven showings of From the Journals of Jean Seberg (to be followed by four more over the next couple of weeks), there are two screenings of a brand-new print of one of Rappaport’s best narrative features, The Scenic Route (1978), along with his remarkable 36-minute tour de force Exterior Night (1994) — a noirish narrative about film noir in which actors filmed in color walk around inside vintage black-and-white Warners sets and locations from the 40s and 50s, shot originally on high-definition video in Germany, and recently transferred to 35-millimeter film. Read more

From Cineaste (Summer 2010, Vol. XXXV, No. 3). — J.R.

Robert Bresson: A Passion for Film

By Tony Pipolo. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. 407 pp. Hardcover: $125 and Paperback: $29.95.

“I do not like to show sex crudely on the screen,” Orson Welles declared in a 1964 interview, pursuing an argument that he also made on other occasions. “Not because of morality or puritanism; my objection is of a purely aesthetic order. In my opinion, there are two things that can absolutely not be carried to the screen: the realistic presentation of the sexual act and praying to God. I never believe an actor or actress who pretends to be completely involved in the sexual act if it is too literal, just as I can never believe an actor who wants to make me believe he is praying.”

It’s an argument that frequently comes to mind when I ponder a certain critical impasse that we often face in considering the films of Robert Bresson, largely due to the dearth of biographical information that we have about him. For a filmmaker whose erotic and spiritual preoccupations seem equally pronounced, Bresson frequently poses the conundrum of how we fill in certain psychological blanks in his characters as well as how we describe and understand matters of the flesh as well as the spirit, as we perceive these matters through what he liked to call his cinematography. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 26, 1993); reprinted in my collection Movies as Politics. — J.R.

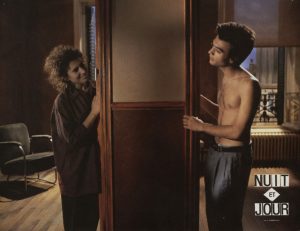

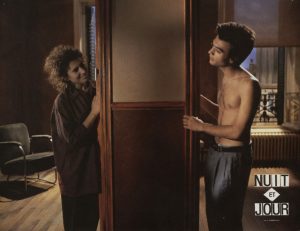

NIGHT AND DAY **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Chantal Akerman

Written by Akerman and Pascal Bonitzer

With Guilaine Londez, Thomas Langmann, François Negret, Nicole Colchat, Pierre Laroche, and Christian Crahay.

Considering all the oppositions that inform the work of Chantal Akerman — such as painting versus narrative, France versus Belgium, being Jewish versus being French and Belgian, and the commercial versus the experimental — it’s only logical that both the plot and the title of her recent Night and Day, one of her best features to date, should reflect the same pattern. The situation it refers to is so simple that it’s hard to describe without making it sound singsongy: Julie (Guilaine Londez) and Jack (Thomas Langmann) — an infatuated young couple from the provinces who’ve recently come to Paris — live in a small flat near Boulevard Sebastopol. During the day they make love; at night Jack drives a taxi and Julie walks the summer streets, singing happily to herself. One night they meet Joseph (François Negret) — another isolated newcomer to Paris — who drives Jack’s cab during the day. Jack heads for his shift; Julie goes walking with Joseph, and they quickly fall in love. Read more

From the June 1982 American Film. — J.R.

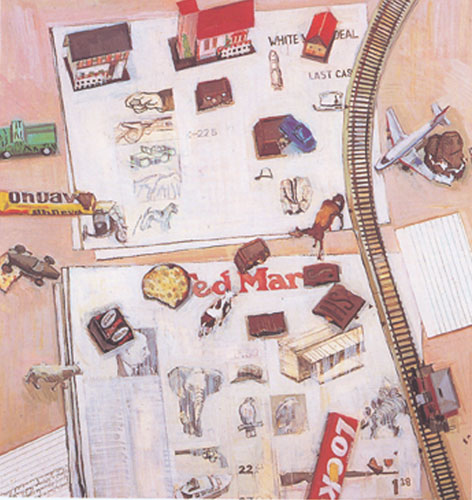

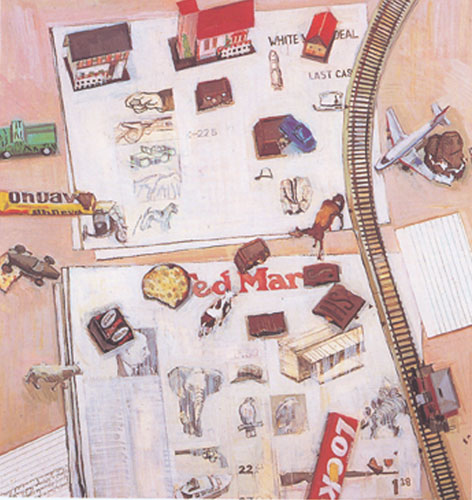

Fans of the brilliant, eccentric, and pioneering film critic Manny Farber who have been regretting his recent absence from the scene simply haven’t been looking in the right places. In fact, the sixty-five-year-old writer, teacher, and former carpenter has been a painter even longer than he’s been a critic, and over the past few years he’s been doing what he calls “auteur” paintings — canvases that recast the subjects and methods of his criticism in a number of fascinating ways.

Using a bird’s-eye view of small objects on a stagelike platform, his paintings, paens to such directors as Howard Hawks [see Howard Hawks II, 1977, 472 x 500, above], Sam Peckinpah, Marguerite Duras, and William Wellman illuminate the filmmakers’ styles and themes. “The compositions and structures are always always based on my take on the directors,” Farber says. “And they’re critical in the fact that I’m usually going away from what I think is known territory, in painting as well as in movies.”

One example of Farber’s oddball approach is his Stan & Ollie, which is full of references to the comedies of Laurel and Hardy, but scarcely uses their faces at all. Read more

This somber black-and-white drama (1950) about a small-town preacher (Joel McCrea) in the postbellum south, narrated by the boy he raised (Dean Stockwell), is one of the most neglected films in the history of cinema as well as Jacques Tourneur’s favorite among his own pictures. (Best known for Cat People and Out of the Past, Tourneur often seemed to thrive in obscurity, and by agreeing to direct this picture at MGM for practically nothing he reportedly sabotaged his own career.) A view of the American heartland that’s emotionally engaged but still charged with darkness (a typhoid epidemic and a near lynching are among its key episodes), it recalls some of John Ford’s best work in its complex perception of goodness, and I can’t think of many films that convey a particular community with more pungency. Margaret Fitts adapted a novel by Joe David Brown; with Ellen Drew, James Mitchell, Juano Hernandez, Amanda Blake, Louis Stone, and Alan Hale. 89 min. (JR)

Read more

Le gamin au vélo/The Kid with a Bike

I’ve recently been thinking that a considerable portion of what I find the most detestable in contemporary commercial filmmaking can be summed up in a single trend: exploitation movies that go out into the world as “serious” art movies,. Admittedly, two very early examples of this trend in talkies, Lang’s M and Hawks’ Scarface, are two of the greatest movies ever made, though neither of these can be accused of stroking and glorifying the audience’s hypocrisy. But ever since the Godfather pictures, it seems, artiness has been working overtime as a kind of built-in alibi for many of the baser impulses in the audience –- various kinds of cynicism viewing corruption as inescapable, everyday, and deeply profound (e.g., Avatar, The Girlfriend Experience, Contagion), extreme violence as a function of specious and hypocritical morality (or, even worse, “sensitivity,” as in Drive — or, for that matter, The Passion of the Christ), gimmicky temporal structures (e.g., Tarantino, Memento, Babel) or fatuous psychologizing that are somehow supposed to dignify various forms of boorishness or nastiness (ranging from McQueen’s sexist complacencies and brutalities in Shame to von Trier’s dubious and ongoing validation of his own depression as a practical tool for coping with glitzy catastrophes and atrocities of his own making), and even the sort of Oscar-mongering that can cast a liberal activist (Woody Harrelson) as a racist thug (Rampart) to show us how “complex” the modern world is supposed to be. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 25, 1992). — J.R.

BOB ROBERTS

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Tim Robbins

With Robbins, Giancarlo Esposito, Ray Wise, Gore Vidal, Alan Rickman, Bob Balaban, John Cusack, Susan Sarandon, Peter Gallagher, James Spader, and Fred Ward.

With Unforgiven unexpectedly topping the box office charts and Bush bashing so popular now that even my favorite comic book, USA Today, seems to do it daily, this appears to be the season of demystification. But I wonder how far the public is prepared to take this process. Since it premiered at the Cannes film festival four months ago, I’ve been looking forward to Tim Robbins’s directorial debut, described as an unbridled attack on the Republican glibness and greed of the past dozen years. Clearly the climate is ripe for some good old-fashioned muckraking. But how much of this involves a genuine change in national perception, and how much is it a merely seasonal media construction? As pleased as I am at the media’s apparent recognition of some of Bush’s crimes, it’s hard for me to understand how this squares with the media’s former position that these crimes never took place (as with Iran-contra) or didn’t matter (as with the savings-and-loan scandal) or were heroic deeds showing both restraint and maturity (as with the slaughter in the Persian Gulf). Read more

From Sight and Sound (Summer 1989). — J.R.

The degree to which contemporary cinema has become a desperate recycling operation was pain fully evident in Berlin this year, where even the better films seemed mired in familiar habits. Aki Kaurismaki’s Ariel, a hard-luck story of an unemployed miner pushed into a life of crime, is basically a Warners B-film of the 1930s, cleanly told and decked out with a few 80s ironies, but really nothing new. Martin Donovan’s Apartment Zero, a baroque male-bonding thriller set in Buenos Aires, superbly acted by Colin Firth and Hart Bochner, offers a chilling and complex view of the American abroad, yet its precise genre positionings would be unthinkable without its cues from Hitchcock, Chabrol and Polanski.

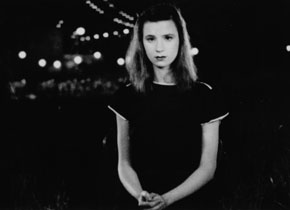

For many colleagues, a major disappointment in the competition was Chantal Akerman’s first English-language feature, Food, Family and Philosophy in French (or Histoires d’Amérique in French), a string of monologues and jokes by Jewish immigrants, delivered against Brooklyn exteriors within hailing distance of the Manhattan skyline over what appears to be a single night. Read more

It seems that I wrote (or completed) this in October 1999, for the American Movie Classics monthly magazine (I don’t recall which issue). — J.R.

The Nutty Professor (1963) — Jerry Lewis’s fourth and in some ways best constructed feature as writer-director-performer — is one of the finest versions of the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde story that we have, and not only because it happens to be the funniest. (It’s also the one with the best music: Les Brown’s band, and memorable versions of both “Stella by Starlight” and “That Old Black Magic”.) A good deal subtler than the raucous Eddie Murphy remake (1996), it illustrates the troubling perception that most of us prefer egotistical bullies to shy, sweet-tempered klutzes. It also provides us with an excellent opportunity for reassessing a multifaceted artist who has seldom received his due in this country.

Critical opinion has often described the overbearing Buddy Love, Lewis’s Mr. Hyde, as a reincarnation of Dean Martin, six years after the decisive breakup of the Martin and Lewis duo. Superficially this sounds like an ingenious notion, but in fact it misses the mark. Part of what’s so disturbing about Buddy Love — making his belated entrance about a third of the way through The Nutty Professor as a romantic stand-in for Julius Kelp, Lewis’s bumbling version of Dr. Read more

From Nashville Scene (cover story), March 10, 2011. This essay was commissioned by the late Jim Ridley, whose unexpected death was a grievous loss.

I’m sorry that I forgot to mention The Young One, surely one of the most neglected and overlooked of all great Southern films, explored in detail elsewhere on this site. — J.R.

In certain respects, the “Visions of the South” series of Southern

movies being launched in Nashville this week at The Belcourt deserves

to be applauded for its omissions as well as its inclusions. The most

conspicuous of these omissions is probably Robert Altman’s Nashville

(1975), which Brenda Lee once aptly described as “a dialectic collage of

unreality.” (Altman, at least, proved better at handling Mississippi —

in Thieves Like Us the year before Nashville, and in Cookie’s

Fortune a quarter of a century later.)

We all know, of course, that Hollywood and even some of its maverick

celebrities have been guilty of fostering and/or perpetuating false images

of the South from the very beginning. A few other prominent and

dubious examples might include Jean Renoir’s The Southerner

(1945), Martin Ritt’s The Sound and the Fury (1959), Richard

Brooks’ Sweet Bird of Youth (1962), Otto Preminger’s Hurry

Sundown (1967), John Frankenheimer’s I Walk the Line

(1970), and, surely the most bogus of all, Alan Parker’s

Mississippi Burning (1989), with its outlandish errors

involving both Jim Crow and the FBI, just to get started. Read more

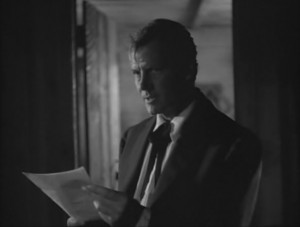

Many of Steven Soderbergh’s better films seem to exist in the shadow of their predecessors. For all its freshness, Sex, Lies, and Videotape, his first feature, was a replay of many self-referential movies about movies dating from the 60s and 70s. The Underneath was a more direct remake, of the 40s noir Criss Cross, and it was an interesting variation rather than any sort of improvement. Yet part of what’s so good about The Limey (1999, 91 min.), a contemporary thriller starring Terence Stamp as an ex-con avenging the death of his daughter, is the way it evokes Point Blank, which is still John Boorman’s best movie. The complex play with time, the metaphysical ambiguity, the stylish wit and violence, and the cool sense of LA architecture all evoke that singular Lee Marvin vehicle. For that matter, a lot of flashback material about the hero as a young man comes straight out of Ken Loach’s Poor Cow (1967). But with or without a sense of where it all comes from, this is a highly enjoyable and offbeat thriller — better to my taste than Soderbergh’s Out of Sight, though similarly quirky in how it sets about telling a story. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 19, 1991).

JU DOU

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Zhang Yimou, in collaboration with Yang Fengliang

Written by Liu Heng

With Gong Li, Li Baotian, Li Wei, Zhang Yi, and Zheng Jian.

Like most people reading this, I know next to nothing about the history of China, which is thousands of years older than the U.S. and has a population over four times as large. In high school I was required to take courses in Alabama and American history; world history was an elective, but if that course had anything to do with China, I no longer recall any details. I also managed to get through seven years of college and graduate school without further edification on the subject.

I suspect that most people in China are comparably uninformed about the U.S. When my youngest brother was in Kenya in the late 60s, he spent time conversing with some Red Guard members who were stationed there, and used to have friendly arguments with them about where Coca-Cola, which they liked, came from; they were convinced it was a product of Kenya. It was difficult for them to accept that anything they liked came from the U.S., Read more

From The Financial Times (Friday, July 2, 1976). This was the second and last time that I took over Nigel Andrews’ weekly film column while he away. — J.R.

Bambi (U)

Odeon, St. Martin’s Lane

Lifeguard (AA)

Ritz

When the Leaves Fall

National Film Theatre

Thirty-four years have passed since Walt Disney’s Bambi first hit the screen. Yet barring only its quaintly dated musical score – six unremarkable tunes by Frank Churchill and Edward Plumb that are well below the usual Disney standard – an unsuspecting child who can’t read Roman numerals might assume that it was made yesterday. It is no small irony that a movie only slightly more than half as old, Silk Stockings (1957), gets treated like a museum piece worthy of nostalgia in the recent That’s Entertainment Part II, while this animated feature gets born afresh for each new generation – not so much like a phoenix rising out of its ashes as like a display of calendar art circulated periodically, with only the dates changing. Read more

Written in 2007 for Criterion, as the commentary for a DVD extra. — J.R.

“As a critic, I already thought of myself as a filmmaker” Godard said in 1962. “Today I still consider myself a critic, and in a sense, I’m even more of one than before. Instead of criticism, I make a film, but that includes a critical dimension. I consider myself an essayist, producing essays in the form of novels or novels in the form of essays: only instead of writing, I film them.”

Three years before he said this, Godard made the first shot in his first feature, appearing just before the title, the explicit declaration of a film critic: “This film is dedicated to Monogram Pictures.”

Why Monogram? Godard never reviewed anything from that studio, which lasted from 1931 to 1953 and mainly produced cheap westerns and series like the Bowery Boys. But shooting on the fly and without sync sound, he wanted to express an alliance to an aesthetic related to impoverished budgets. So this wasn’t any sort of fan’s homage, as it would have been if it had come from one of the American movie brats; it was a critical statement of aims and boundaries. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 27, 1998). — J.R.

The Gingerbread Man

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by John Grisham and Al Hayes

With Kenneth Branagh, Embeth Davidtz, Robert Downey Jr., Daryl Hannah, Tom Berenger, and Robert Duvall.

Some people are going to go to The Gingerbread Man looking for a John Grisham movie, and some are going to go looking for a Robert Altman film. Both are likely to be disappointed.

The alliance may have been a shotgun marriage presided over by desperate commerce, though the movie’s press book works overtime trying to put a positive spin on it: “Both Altman and Grisham champion the causes of Everyman underdogs who are fighting the system. Indeed, in their own different ways, these two artists are mavericks, outsiders-by-choice who examine a system and an orderly regimen that they have long ago abandoned. John Grisham left a successful legal practice for an even more lucrative literary career based in large part on his ability to accurately depict the shortcomings of our legal system and the behind-the-scenes machinations that are a routine part of that profession. And against considerable odds, Robert Altman has bucked the Hollywood establishment for 30 years, continuing to make distinctly personal movies exactly the way he wants to make them, ignoring the marketing driven, lowest-common-denominator sensibilities that seem to determine which studio films actually get made.” Read more