This very lengthy essay was assembled in 2013 out of several previous pieces of mine, but I no longer recall the occasion for it. — J.R.

Introduction

One of the problems inherent in using the term “cult” within a contemporary context relating to film, either as a noun or as an adjective, is that it refers to various social structures that no longer exist, at least not in the ways that they once did. When indiscriminate moviegoing (as opposed to going to see particular films) was a routine everyday activity, it was theoretically possible for cults to form around exceptional items — “sleepers,” as they were then called by film exhibitors — that were spontaneously adopted and anointed by audiences rather than generated by advertising. But once advertising started to anticipate and supersede such a selection process, the whole concept of the cult film became dubious at the same time it became more prominent, a marketing term rather than a self-generating social process.

Joe Dante deserves a special place in what I would call the post-cult cinema because he is one of the few commercial American directors I know who has refused to hire a personal publicist, and for tactical reasons — someone, in short, who chooses to be recognized at best only by initiates (that is, by fellow cultists or would-be cultists, his comrades-in-arms) rather than by the public at large. Read more

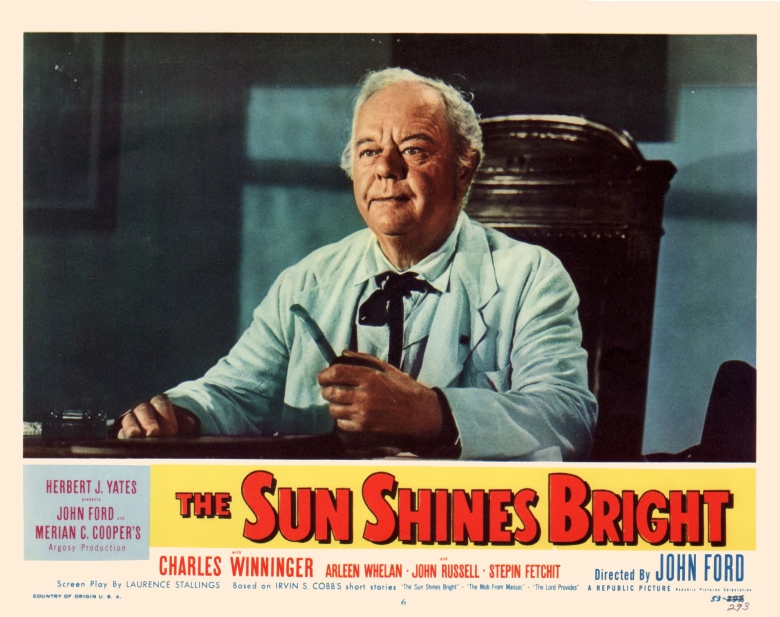

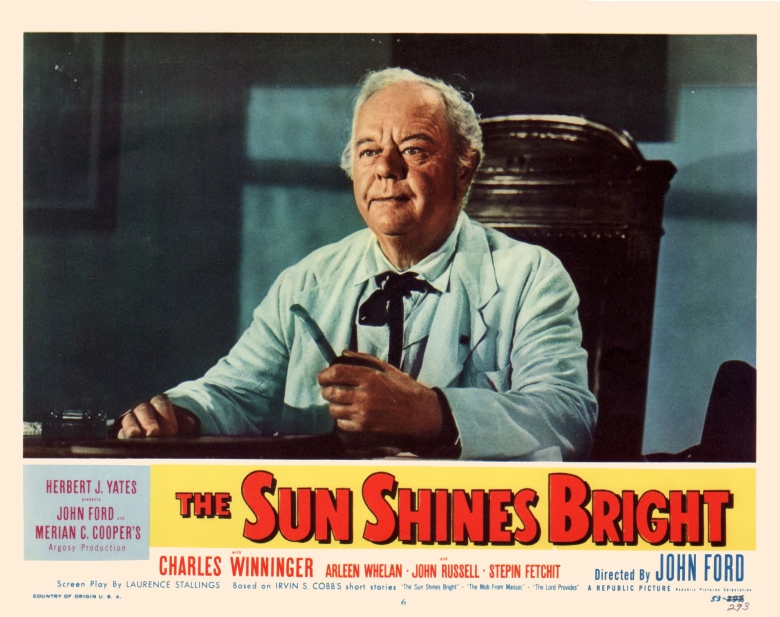

This was originally published by the Viennale in 2004 as part of a catalogue (Die Früchte des Zorns und der Zärtlichkeit) accompanying a program of John Ford films selected by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet; it subsequently appeared online in Rouge no. 7 (2005). One can also access Kevin Lee’s two-part video featuring my commentary on both The Sun Shines Bright and Gertrud here and here. — J.R.

“The Doddering Relics of a Lost Cause”: John Ford’s The Sun Shines Bright

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

My father helped to run a small chain of movie theaters in northwestern Alabama that were owned by my grandfather while I was growing up. He and my mother weren’t cinephiles, but on two separate occasions they took the trouble to travel to cities in different states to attend world premieres in the South while I was growing up. One was for a big Southern film from a big studio (M-G-M), Gone with the Wind, held in 1939 in Atlanta. The other was for a small Southern film from a small studio (Republic Pictures), The Sun Shines Bright, held in 1953 in what I believe was a city in Tennessee — most likely Nashville or Chattanooga, possibly Memphis or Knoxville. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 20, 1987). — J.R.

CROSS MY HEART

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Armyan Bernstein

Written by Armyan Bernstein and Gail Parent

With Martin Short, Annette O’Toole, Paul Reiser, and Joanna Kerns.

Like a 3-D movie, in which the illusion of depth is utterly dependent on the spectator’s rigidly foursquare frontal viewing position, Armyan Bernstein’s Cross My Heart is flat and fuzzy around the edges; tilt your head slightly, and the roundness of the characters vanishes immediately. But because the characters holding the center of the screen are nearly always Martin Short and Annette O’Toole — consummate pros commanding and regulating the space between and around them like two generals at a summit conference — there’s rarely any reason to look aside; our attention is riveted.

For all their charisma, one wouldn’t have thought O’Toole or Short capable of such mastery on the basis of their separate and earlier outings. Despite his frequent brilliance on SCTV and Saturday Night Live, mainly as a parodist of narcissistic TV and movie personalities ranging from Dick Cavett to Jerry Lewis (by way of Katharine Hepburn), Short was both literally and figuratively dwarfed by Steve Martin and Chevy Chase in Three Amigos, although admittedly all three amigos were mainly stranded by the anemic comic material. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 17, 1992). — J.R.

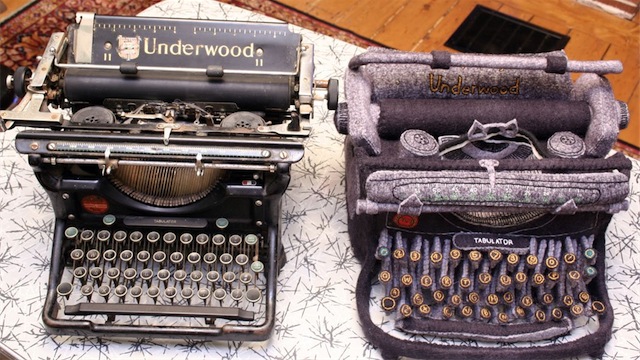

NAKED LUNCH **** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by David Cronenberg

With Peter Weller, Judy Davis, Ian Holm, Julian Sands, Roy Scheider, Monique Mercure, Michael Zelniker, and Nicholas Campbell.

And some of us are on Different Kicks and that’s a thing out in the open the way I like to see what I eat and vice versa mutatis mutandis as the case may be. Bill’s Naked Lunch Room . . . Step right up. Good for young and old, man and bestial. Nothing like a little snake oil to grease the wheels and get a show on the track Jack. Which side are you on? Fro-Zen Hydraulic? Or you want to take a look around with Honest Bill?” — William S. Burroughs, introduction to Naked Lunch (1962)

The first time I read William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch—or at least large portions of it — was in 1959, a few months after its first printing, in a smuggled copy of the seedy Olympia Press edition fresh from Paris. As I recall it was missing most or all of the accompanying matter — the introduction (“Deposition: Testimony Concerning a Sickness”), “Atrophied Preface” (“Wouldn’t You?”), Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 29, 2005); slightly tweaked in February 2014. — J.R.

Michael Cimino’s 1980 epic, about immigrant settlers clashing with native capitalists in 19th-century Wyoming, suffered a disastrous opening and was subsequently cut by 70 minutes; it became a legendary flop in the U.S., though the original 219-minute cut was widely applauded as a masterpiece in Europe. The longer version is impressive as long as the characters and settings remain in long shot; only when the camera gets closer do the problems start. The story is both slow moving and hard to follow, but the locations and period details offer plenty to ponder. Cimino’s handling of class issues is ambitious and unusually blunt, though it’s debatable whether this adds up to any sort of Marxist statement, except perhaps as a belated response to the (Oscar-winning) racism and xenophobia of his previous feature, The Deer Hunter. There’s no question that the same homoerotic — and arguably sexist — vision runs through both movies, as well as Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, the Cimino feature that preceded them. With Kris Kristofferson, Christopher Walken, Isabelle Huppert, Jeff Bridges, Sam Waterston, John Hurt, Joseph Cotten, and Brad Dourif. R. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Written in 2013 for a 2019 Taschen volume. — J.R.

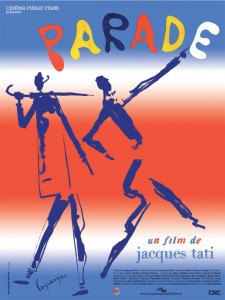

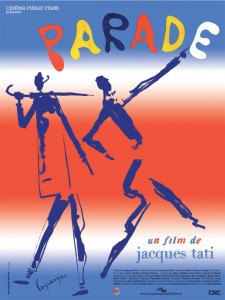

Parade

1.Why is Parade Tati’s least known feature?

It’s surprising how many of Jacques Tati’s fans still haven’t seen his last feature, and in some cases don’t even know about its existence. Yet the reasons for this neglect aren’t too difficult to figure out.

For one thing, Parade is the only Tati feature apart from Jour de fête in which his best known and most beloved character, Monsieur Hulot, doesn’t appear. For another thing, it was made on an extremely modest budget, and shot mostly on video for Swedish television; it never received even a fraction of the advertising and other forms of promotion, much less distribution, accorded to his five earlier pictures. And some of those who have seen it don’t even regard it as a feature, but think of it merely as a documentary of a circus performance in which Tati appears only as an emcee and as one of the performers, doing some of his more famous pantomime routines. It doesn’t have a story in the sense that all his previous films do on some level, including even his early short, L’école des facteurs (1947).

On the other hand, what we mean by “story” is already a bit different in the work of Tati than it is in the work of most other important filmmakers, comic and otherwise. Read more

James B. Harris’s second feature, which I discovered and saw several times in Cannes in 1973, continues to be a particular favorite among unclassifiable films, and it has finally become available digitally (and was even recently shown on TCM). My initial review of the film for Film Comment led to be getting invited to dinner once by Harris himself along with his French distributor, Pierre Rissient; this review appeared a couple of years later, in the Autumn 1975 issue of Sight and Sound, after the film opened belatedly in London. Note: This film has also sometimes gone under the titles Sleeping Beauty and Dream Castle. — J.R. Read more

This appeared in the Chicago Reader’s November 8, 2002 issue. –J.R.

Femme Fatale

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Brian De Palma

With Antonio Banderas, Rebecca Romijn-Stamos, Peter Coyote, Gregg Henry, Rie Rasmussen, and Eriq Ebouaney.

By my count, Femme Fatale is Brian De Palma’s 26th feature, and as I watched it the first time two months ago I found myself capitulating to its inspired formalist madness — something I’ve resisted in his films for the past 30-odd years. De Palma’s latest isn’t so much an improvement on his earlier work as a grand synthesis of it — as if he set out to combine every previous thriller he’d made in one hyperbolically frothy cocktail. So we get split-screen framing; bad girls; sweetie-pie male suckers; verbal and physical abuse; lots of blood; a melodramatic story stretched out over many years; slow-motion, lyrically rendered catastrophes; noirish lighting schemes favoring venetian blinds; it-was-all-a-dream plot twists; scrambled and recomposed plot mosaics; obsessional repetitions of sound and image; pastiches of familiar musical pieces (in this case Ravel and Satie); nearly constant camera movements; and ceiling-height camera angles. Best of all, we often get several of these things simultaneously. (One of the few De Palma movies for which he takes sole script credit, Femme Fatale is nothing if not personal.) Read more

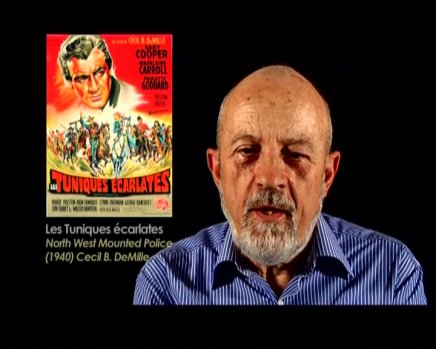

This fairly recent (and much more recently updated) piece is a sequel to my earlier “À la recherche de Luc Moullet: 25 Propositions,” originally written and published in 1977. –J.R.

Moullet retrouvé

Almost thirty years have passed between my extended defense of Luc Moullet in Film Comment and the long-overdue launch of the first American retrospective devoted to this mainly comic French filmmaker, who’s also a critic. But it was worth the wait. In the spring of 2006, “Luc Moullet: Agent Provocateur of the New Wave,” including eight of his 32 films, showed up at Chicago’s Gene Siskel Film Center. And three years later, a complete Moullet retrospective was shown in Paris, accompanied by much fanfare, including the publication of a DVD featuring ten of his best short films, Luc Moullet en shorts, and three separate books: a lengthy interview with Emmanuel Burdeau et Jean Narboni (Notre Alpin Quotidien, 130 pages) and a long-overdue collection of his film criticism (Pige Choisies [De Griffith à Ellroy], 372 pages), both published by Capricci, and a study of King Vidor’s The Fountainhead (Le Rebelle de King Vidor: les arêtes vives), published by Yellow Now.

Moullet started out in the mid-1960s as a neoprimitive, brandishing his lack of technique while reflecting some of the tenderness of Francois Truffaut’s films of that period as well as some of the boorish satirical humor of Jean-Luc Godard’s. Read more

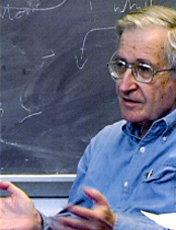

In my original review of this documentary, I cited and recommended some writing by Eliot Weinberger that three of my editors regarded as irresponsible and unreliable and therefore something that shouldn’t be mentioned, along with some of my own pronouncements. Readers who would like to judge this matter for themselves can read my unedited draft, which I’ve added below the published version. The edited version appeared in the February 7, 2003 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Power and Terror: Noam Chomsky in Our Times

*** (A must-see)

Directed by John Junkerman.

As a work of cinema, John Junkerman’s documentary about Noam Chomsky doesn’t set the world on fire. The film is a prosaic compilation of interview footage of the linguist and political analyst in his office at MIT intercut with footage of him speaking in Palo Alto, Berkeley, and the Bronx last spring. He’s also shown chatting with students about U.S. foreign policy, the “war on terrorism,” and representations of both in the American media. Unlike Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick’s Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media (1992), a Canadian film that’s well over twice as long, Power and Terror: Noam Chomsky in Our Times doesn’t try to offer a comprehensive portrait of its subject or a wide-ranging survey of his thought. Read more

One of my first published reviews, which appeared in the November 2, 1972 issue of The Village Voice, this was commissioned by Andrew Sarris, bless him. I was always grateful for this opportunity to write about a film that I love, and that I continue to cherish. — J.R.

Jonas Mekas’s Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania, a film dedicated “to all the displaced people in the world,” has itself become the object of some displacement. Screened jointly with Adolfas Mekas and Pola Chapelle’s Going Home at the New York Film Festival, defined in the program as a non-narrative film and by its author as a home movie, it has become a casual victim of “convenient” programing and somewhat deceptive labels. Whatever “non-narrative” and “home movie” mean — and I think the latter describes Going Home pretty accurately — they are less than helpful in describing the achievement of what must be called Jonas Mekas’s testament. If they must be understood, let it be understood that Reminiscences is a home movie about homelessness, a non-narrative film with one of the most beautifully constructed and articulated narrative lines in autobiographical cinema.

Going Home, a rambling collection of travel photos and family poses, resembles the jazzy surfaces of Hallelujah the Hills, joke titles and all, and registers not unlike a boastful list of possessions (the secret metaphysic behind every family album): this is my garden, my Moscow, my family, my Lithuania. Read more

The following article appeared in the February 23, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

ART OF MUSIC VIDEO

For people like myself who have conflicted feelings about music videos as an art form, the four-part series Art of Music Video — playing for the second time at the Film Center this weekend — offers lots of material to consider. Even so, this presentation of a hundred videos assembled by Michael Nash of the Long Beach Museum of Art involves a number of curatorial decisions that I have problems with. Before considering the videos themselves, let me list these problems; some of them are overlapping rather than consecutive, but putting them in list form will help to give some idea of how many boats this particular series is missing:

(1) Historical. Although Nash’s selection is media-specific—that is, generally limited to videos—one of his four programs, “Vanguard Re-visions,” has a subcategory called “Experimental Film: Invention and Intervention,” consisting of films made by Bruce Conner, James Herbert, and Jem Cohen between 1961 and 1989.

While I have no quarrel with the inclusion of these figures, it’s clear that this attempt to give a foreshortened art-history perspective rules out a lot more of the history of music videos and their precursors than it includes. Read more

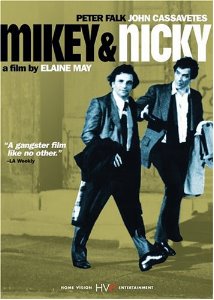

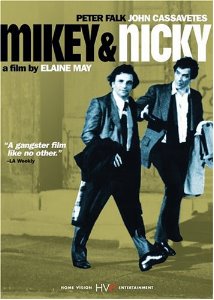

This was written in October 2003 for the DVD released in 2004 by Home Vision Entertainment. DVD Beaver persuasively argues that this edition (currently unavailable, alas) is far superior to the Region 2 PAL release on Odyssey Video. — J.R.

Thanks to an appointment book, I can pinpoint that the first time I saw Mikey and Nicky was on January 7th, 1977, at New York’s Little Carnegie. The experience was a shock. In contrast to A New Leaf (1971) and The Heartbreak Kid (1972) —- Elaine May’s two previous features, both slick (if caustic) Hollywood comedies —- this was a harsh gangster drama in drab urban locations, and, even stranger, a near-facsimile of John Cassavetes’s raw independent features, costarring Cassavetes himself as Nicky and one of his regulars, Peter Falk, as Mikey. The editing was full of continuity errors, the garrulous performances free-wheeling and seemingly full of improvisations (as I then wrongly assumed Cassavetes’ own features were). But the brutal force of an alternately nurtured and betrayed friendship between two small-time crooks over one long night in Philadelphia was so ferocious that it left me shaken as well as bewildered.

The second time I saw the film was in 1980, when I programmed it for “Buried Treasures” at the Toronto Film Festival; this inadvertently became the world premiere of the film’s final version. Read more

The following was written specifically for the first (and much shorter) edition of Movie Mutations, a collection of nine letters published in Spanish translation by Ediciones Nuevos Tiempos as Movie Mutations: Cartas de cine in the spring of 2002 at the 4th Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema, and revised only slightly for its publication here. (It originally appeared in English in the online Senses of Cinema, May-June 2002.) — J.R.

***

March 23, 2002

Dear Quintín and Flavia (1),

I guess it must seem excessive, starting off a book of letters with yet another letter –- and rounding off a neat dozen of them with an unlucky thirteenth in the bargain. Skeptics who will find the following correspondence too chummy and cozy for comfort are apt to be equally or even more irritated by this Preface, but I can’t see any way out of this dilemma. When you, Flavia, asked me to write this less than a week ago -– emailing me that as the instigator of a project called “Movie Mutations”, I should be the one to introduce it in its initial book form — my first rude response, uttered only to myself, was, “But haven’t I done this already? Read more

From the Chicago Reader, June 20, 1997. — J.R.

The Big Sleep

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Howard Hawks

Written by William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, and Jules Furthman

With Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, John Ridgely, Martha Vickers, Dorothy Malone, Pat Clark, Regis Toomey, Charles Waldron, Sonia Darrin, and Elisha Cook Jr.

For all its reputation as a classic, and despite the greatness of Howard Hawks as a filmmaker, The Big Sleep has never quite belonged in the front rank of his work — at least not to the same degree as Scarface, Twentieth Century, Only Angels Have Wings, To Have and Have Not, Red River, The Big Sky, Monkey Business, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and Rio Bravo, to cite my own list of favorites. Unlike To Have and Have Not (1944) — Hawks’s previous collaboration with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, writers Jules Furthman and William Faulkner, cinematographer Sid Hickox, and composer Max Steiner — it qualifies as neither a personal manifesto on social and sexual behavior nor an abstract meditation on jivey style and braggadocio set within a confined space, though it periodically reminds one that exercises of this kind are what Hawks did best. Read more