From the Chicago Reader (February 21, 1997). It’s worth noting that Japanese doesn’t distinguish between singular and plural, so that the film is also known as The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum, which is an equally accurate translation. — J. R.

Though not the best known of Kenji Mizoguchi’s period masterpieces, this 1939 feature is conceivably the greatest. (For me the only other contender is Sansho the Bailiff.) The plot, which oddly resembles that of There’s No Business Like Show Business, concerns the rebellious son of a theatrical family devoted to Kabuki who leaves home for many years, perfects his art, aided by a working-class woman who loves him, and eventually returns. Apart from the highly charged and adroitly edited Kabuki sequences, the film is mainly constructed in extremely long takes, and an intricate rhyme structure between two time periods is developed by matching camera angles in the same locations. Never before or since (apart from The 47 Ronin) has Mizoguchi’s refusal to use close-ups been more telling, and the theme of female sacrifice that informs most of his major works is given a singular resonance and complexity here. Demonstrating an uncanny mastery of framing and camera movement, the film also has a complexity of characterization that’s shown with sublime economy. Read more

I’m sorry that the Chicago Reader in its current issue chooses not to acknowledge that it’s anything special or worthy of more than cursory notice, but Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day is probably the greatest Taiwanese film ever made, and it doesn’t turn up here often. Doc Films is showing it at 7 pm. Here’s my original capsule review, only slightly updated:

Bearing in mind Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, this astonishing 230-minute epic (1991) by Edward Yang (1947-2007), set over one Taipei school year in the early 60s, would fully warrant the subtitle “A Taiwanese Tragedy.” A powerful statement from Yang’s generation about what it means to be Taiwanese, superior even to his later masterpiece (and final film) Yi Yi (2000), it has a novelistic richness of character, setting, and milieu unmatched by any other 90s film (a richness only partially apparent in its three-hour version). What Yang does with objects — a flashlight, a radio, a tape recorder, a Japanese sword — resonates more deeply than what most directors do with characters, because along with an uncommon understanding of and sympathy for teenagers Yang has an exquisite eye for the troubled universe they inhabit. This is a film about alienated identities in a country undergoing a profound existential crisis — a Rebel Without a Cause with much of the same nocturnal lyricism and cosmic despair. Read more

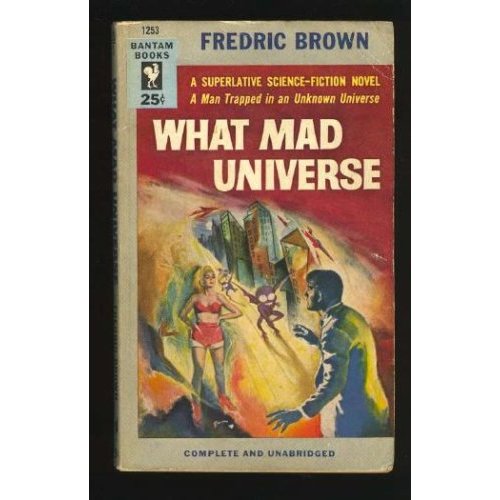

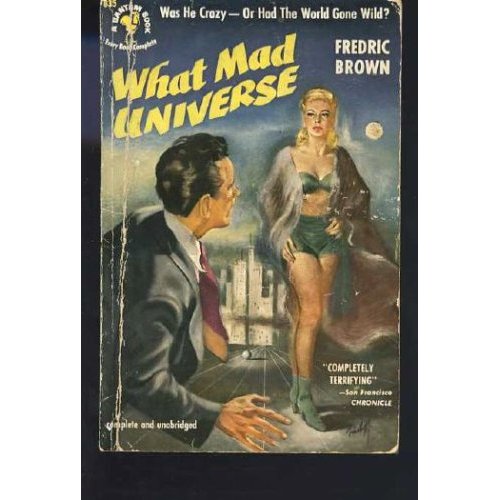

One of my favorite writers since childhood has been the prolific Fredric Brown (1906-1972), both for his mysteries and his science fiction. The former is much more plentiful than the latter—so much so that it’s been possible in recent years to publish practically all his science fiction in two thick hardcover volumes, From These Ashes (the short stories, 690 pages) and Martians and Madness (the novels, 633 pages). (The “madness” in the latter title partially relates to What Mad Universe, Brown’s best SF novel, as well as one of his very best SF stories, “Come and Go Mad”, although it also qualifies as an ongoing Brown theme in some of the mystery plots as well.)

On the other hand, it might take an AIG bonus to pay for all of Brown’s out-of-print mystery, crime, and detective fiction; some of the 19 or so limited-run paperback collections devoted to the stories that were published in the 80s and 90s now sell on the Internet for close to a thousand bucks apiece, and a few of the novels are comparably pricey.

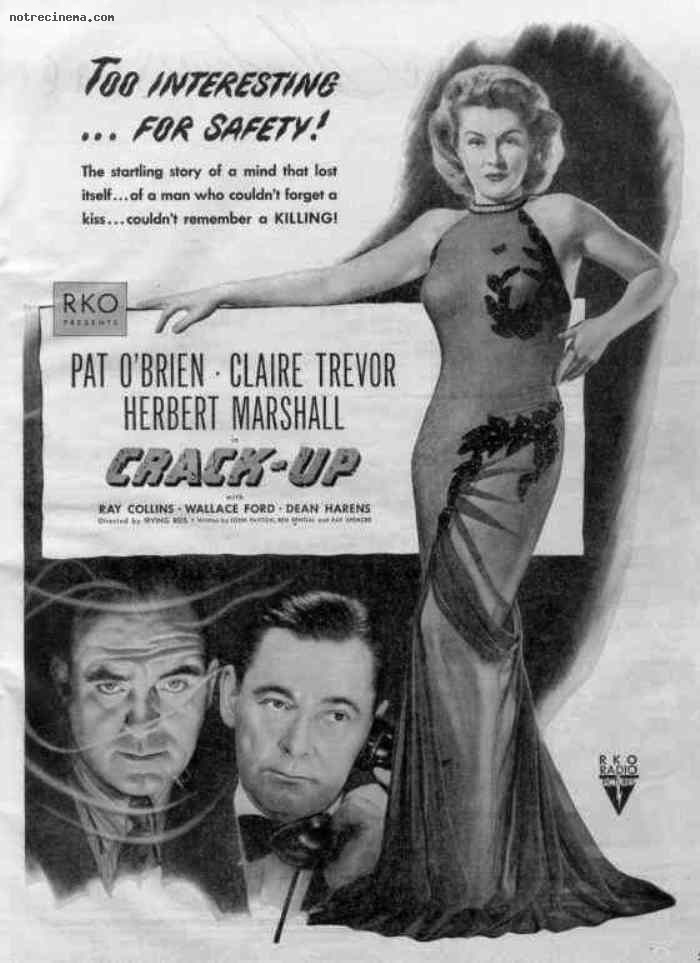

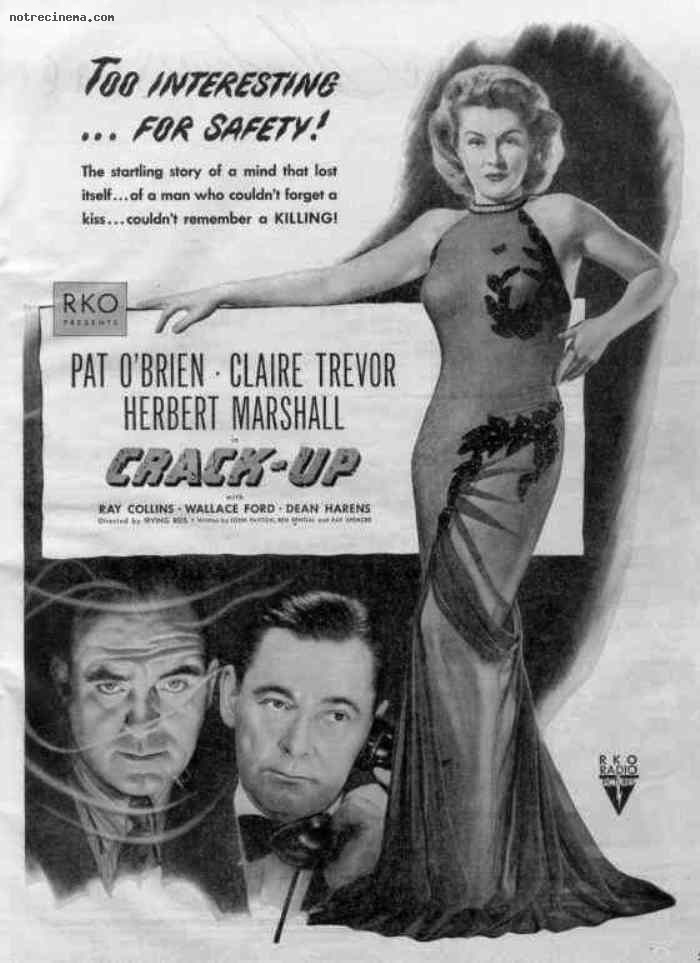

Probably the two best known Hollywood features derived from Brown mysteries are Screaming Mimi (Gerd Oswald, 1958) and Crack-Up (Irving Reis, 1946)—the latter derived from a 1943 Brown novella called “Madman’s Holiday” that’s now available only in one of those limited-run paperbacks that currently sells for $995 and $950 on Amazon, hideous jacket (see below) and all. Read more