From the Chicago Reader (June 8, 2007) — J.R.

PRIVATE FEARS IN PUBLIC PLACES ****

DIRECTED BY ALAIN RESNAIS | WRITTEN BY JEAN-MICHEL RIBES AND ALAN AYCKBOURN

WITH SABINE AZEMA, ISABELLE CARRE, LAURA MORANTE, PIERRE ARDITI, ANDRE DUSSOLLIER, AND LAMBERT WILSON

It might sound crazy to call Alain Resnais the last of the great Hollywood studio directors when he’s never made a single movie in Hollywood. But classic Hollywood filmmaking, as defined by the aesthetics and craftsmanship of the system from the 30s through the 60s, transcends location. Indeed, many of the best recent examples, like Black Book and Angel-A, are European. And from its breathtaking opening shot, which sweeps across a wintry Parisian cityscape to the windows of an apartment house just as blinds are lowered and a door slams, the director’s newest film, Private Fears in Public Places, clearly belongs to that tradition.

Made by Resnais in his mid-80s, this movie is a real heart-breaker—one reason I prefer the French title, Coeurs (“hearts”). Derived from a recent play by Alan Ayckbourn (Resnais also adapted his Intimate Exchanges for the 1993 film Smoking/No Smoking), Private Fears in Public Places is a labyrinthine tale of crisscrossing destinies, missed connections, enclosures that poignantly echo one another, and muffled romantic and erotic feelings. Read more

This review appeared originally in Fanzine, 6/26/08. –J.R.

Given the size of his achievement, it’s astonishing that Jacques Tati made only half a dozen features, none of them bad. But if I had to single out any of these as a lesser work, I’d pick Trafic (1971), the only one that qualifies as compromised.

Others might select Parade (1973), Tati’s final film –– because it was mainly shot on video and virtually dispenses with plot by basically following the contours of a far-from-spectacular circus performance. But they’d be wrong. Though it’s the least known Tati feature and the most modest in terms of budget, Parade is by no means Tati’s least ambitious or adventurous film. In some ways it even qualifies as his most radical –– in its refusal to clearly separate life from spectacle or prioritize professional performers over unprofessional spectators. Unfortunately, the less analytical and more sentimental celebrations of Tati –– including the charming 1989 documentary by the late Sophie Tatischeff about her father, In the Footsteps of Monsieur Hulot, that’s a bonus on the second disc here –– tend to overlook this radicalism.

Trafic, on the other hand, represented a conscious step backward for Tati. Read more

This very lengthy essay was assembled in 2013 out of several previous pieces of mine, but I no longer recall the occasion for it. — J.R.

Introduction

One of the problems inherent in using the term “cult” within a contemporary context relating to film, either as a noun or as an adjective, is that it refers to various social structures that no longer exist, at least not in the ways that they once did. When indiscriminate moviegoing (as opposed to going to see particular films) was a routine everyday activity, it was theoretically possible for cults to form around exceptional items — “sleepers,” as they were then called by film exhibitors — that were spontaneously adopted and anointed by audiences rather than generated by advertising. But once advertising started to anticipate and supersede such a selection process, the whole concept of the cult film became dubious at the same time it became more prominent, a marketing term rather than a self-generating social process.

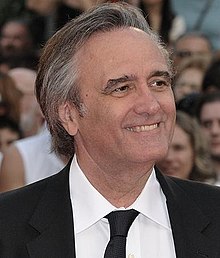

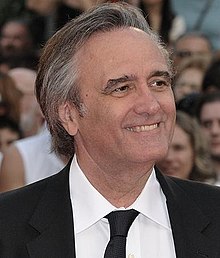

Joe Dante deserves a special place in what I would call the post-cult cinema because he is one of the few commercial American directors I know who has refused to hire a personal publicist, and for tactical reasons — someone, in short, who chooses to be recognized at best only by initiates (that is, by fellow cultists or would-be cultists, his comrades-in-arms) rather than by the public at large. Read more