From the Chicago Reader (April 29, 2005); slightly tweaked in February 2014. — J.R.

Michael Cimino’s 1980 epic, about immigrant settlers clashing with native capitalists in 19th-century Wyoming, suffered a disastrous opening and was subsequently cut by 70 minutes; it became a legendary flop in the U.S., though the original 219-minute cut was widely applauded as a masterpiece in Europe. The longer version is impressive as long as the characters and settings remain in long shot; only when the camera gets closer do the problems start. The story is both slow moving and hard to follow, but the locations and period details offer plenty to ponder. Cimino’s handling of class issues is ambitious and unusually blunt, though it’s debatable whether this adds up to any sort of Marxist statement, except perhaps as a belated response to the (Oscar-winning) racism and xenophobia of his previous feature, The Deer Hunter. There’s no question that the same homoerotic — and arguably sexist — vision runs through both movies, as well as Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, the Cimino feature that preceded them. With Kris Kristofferson, Christopher Walken, Isabelle Huppert, Jeff Bridges, Sam Waterston, John Hurt, Joseph Cotten, and Brad Dourif. R. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Written in 2013 for a 2019 Taschen volume. — J.R.

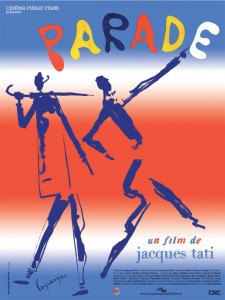

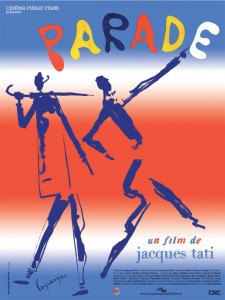

Parade

1.Why is Parade Tati’s least known feature?

It’s surprising how many of Jacques Tati’s fans still haven’t seen his last feature, and in some cases don’t even know about its existence. Yet the reasons for this neglect aren’t too difficult to figure out.

For one thing, Parade is the only Tati feature apart from Jour de fête in which his best known and most beloved character, Monsieur Hulot, doesn’t appear. For another thing, it was made on an extremely modest budget, and shot mostly on video for Swedish television; it never received even a fraction of the advertising and other forms of promotion, much less distribution, accorded to his five earlier pictures. And some of those who have seen it don’t even regard it as a feature, but think of it merely as a documentary of a circus performance in which Tati appears only as an emcee and as one of the performers, doing some of his more famous pantomime routines. It doesn’t have a story in the sense that all his previous films do on some level, including even his early short, L’école des facteurs (1947).

On the other hand, what we mean by “story” is already a bit different in the work of Tati than it is in the work of most other important filmmakers, comic and otherwise. Read more

James B. Harris’s second feature, which I discovered and saw several times in Cannes in 1973, continues to be a particular favorite among unclassifiable films, and it has finally become available digitally (and was even recently shown on TCM). My initial review of the film for Film Comment led to be getting invited to dinner once by Harris himself along with his French distributor, Pierre Rissient; this review appeared a couple of years later, in the Autumn 1975 issue of Sight and Sound, after the film opened belatedly in London. Note: This film has also sometimes gone under the titles Sleeping Beauty and Dream Castle. — J.R. Read more